It was an ordinary Friday evening in September, perhaps already giving way to Saturday morning bleariness, when I turned to my partner, half-asleep, and said “Bae, I think I’m going to join a union.”

It would have been absolutely ridiculous to even consider this possibility at the grim start of 2019. I was writing between shifts at a busy wine store, scraping together assignments over weekends, working six days and a half days a week, and leaning on my partner’s much better-paying, stable job. (He describes his work as “acceptable in Marxist Spain,” building houses and restoring old Victorians with a small group of immigrants from England and Mexico.) It seemed like this would go on forever, that this was the future promised in this right-to-work state, where union membership remains hamstrung by legislation, intimidation, and broken social infrastructure, then compounded by racism. I was selling the hottest hipster beer around, made by people making thirteen dollars an hour with no benefits—if they were lucky—while I made even less. There was a common joke among my friends: I know a lot of PhDs—we serve each other drinks every weekend.

At the beginning of this year, a time which now seems a lifetime’s distance away, the whole country’s labor force was convulsing. Federal employees hadn’t been paid in months. TSA workers were going to foodbanks. On January 22, United Airlines employee Sara Nelson, who serves as president of the Flight Attendants Union (CWA AFL-CIO), gave a rousing speech calling for every American worker to go on a general strike, an idea that hadn’t been voiced publicly in over fifty years. This wasn’t about negotiating for higher wages or healthcare: it was about getting paid at all. According to the New York Times, when a labor historian approached Nelson after her speech, concerned that a general strike was too radical, she smiled and said, “Strike. Strike, strike, strike, strike, strike, strike. Say it. It feels good.” In West Virginia, teachers were again on strike, almost a year to the day after their illegal wildcat strike kicked off waves of similar strikes in red states. If it’s this bad now, it can’t get much worse.

It didn’t. Things, impossibly, started getting better. Teachers demanded raises, full-time librarians and nurses, healthcare, and real pensions. Sara Nelson’s call for grounding planes paid off, and the government shutdown was over in a matter of hours once the planes stopped leaving New York. Anchor Brewing, one of the oldest independent craft breweries in the United States, unionized in March. This magazine became W.A.G.E. certified on March 24, committing itself to fairly paying contributors for their work and becoming one of only two certified institutions in the state of Georgia, where right-to-work laws reign. Institutions in neighboring Alabama are exploring becoming W.A.G.E certified in the coming months.

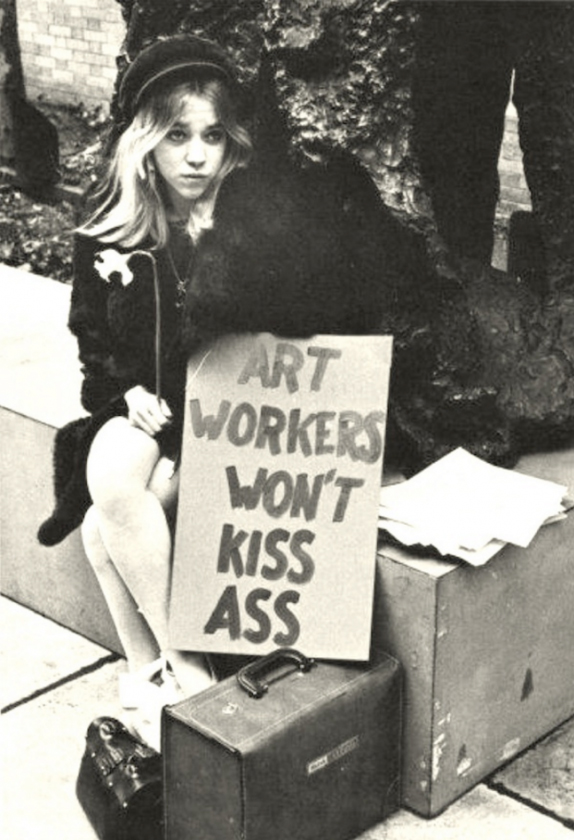

The common language around what I do and others like me do started changing this spring. We are now “cultural workers” and’ “art workers,” no longer specifying what kind of art we make or what other fields we work in. A recent Harvard poll claimed that thirty-seven percent of people between the ages of 18 and 29 said they favored a “militant labor movement” in the United States, and a full forty percent of the same age group said they wanted companies with profits over a billion dollars to have forty percent of their boards made up of workers and their representatives. Thirty-five percent of new union members are under the age of 40, and one in four new jobs is union. Young people in all kinds of industries and professions want something else, something they aren’t getting now, and if current trends continue, millennials will be working through their 80s, with one in five currently living in poverty, and over half fearful for their future.

Fear and want, as always, remain the defining conditions of vulnerability. Fear and want are why I, like many other workers, joined a union. While working on this collaborative series with Scalawag exploring art and labor, I witnessed whole industries ravaged by the changing media landscape, countless women who participated in strikes and led them, and eventually found a union of my own: the National Writers Union, which lives under the umbrella of the United Automakers Union, Local Number 1981. I checked my bank account to see if I could afford dues, then filed my paperwork and, almost thrillingly, became a rank-and-file union member.

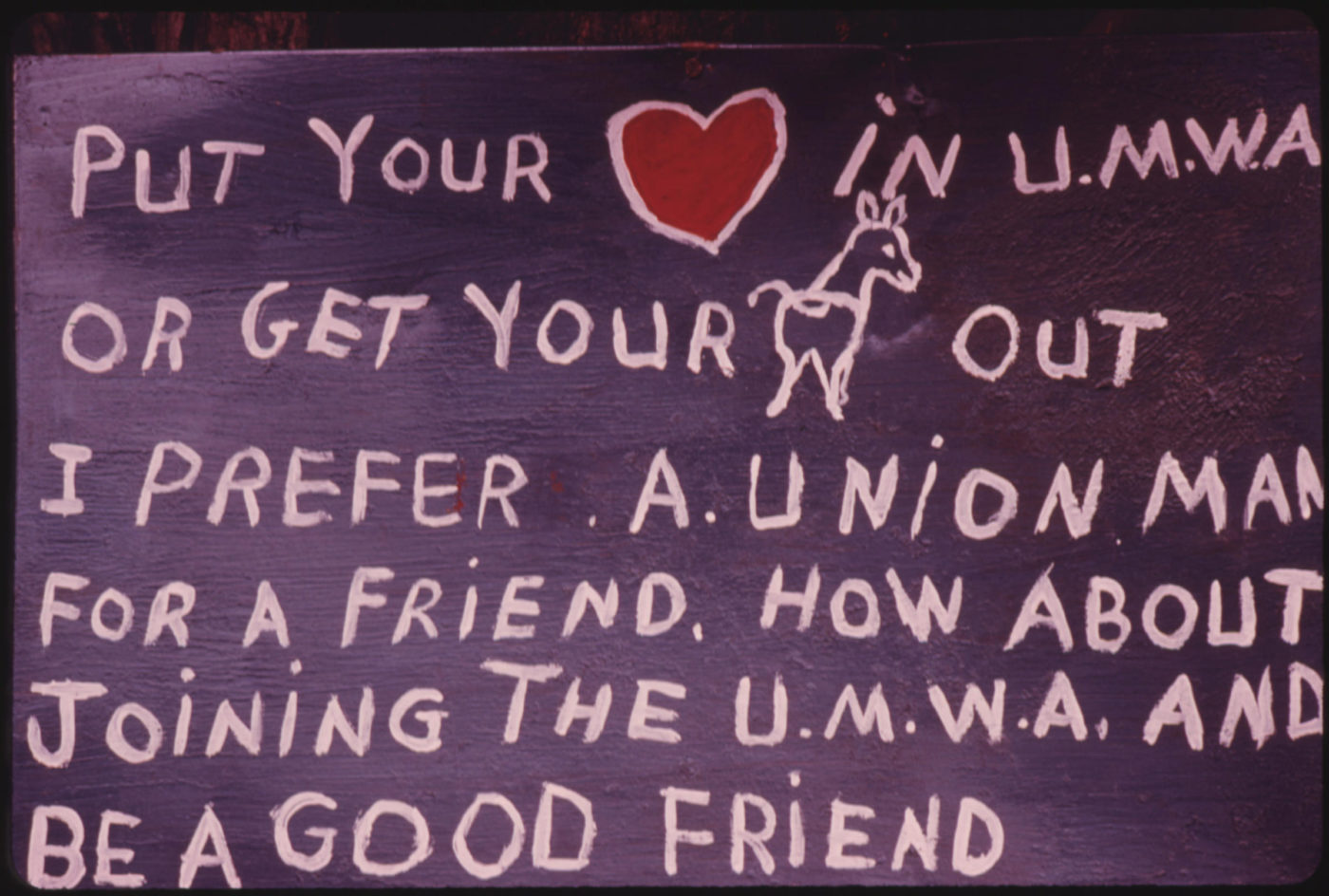

The next morning I was ebullient. I felt powerful, strong, not alone! My partner and I looked at old union stickers and signs together, listened to the Smithsonian field recordings of labor songs, and talked about what had previously been unimaginable—health insurance.

In her keynote address at the American Writers Congress in October 1981, the late Toni Morrison said, “[It] is not as individuals that we are abused and silenced; it is as writers… We may be dreamers or scholars, we may need tranquility or chaos—we may write for posterity or for the hour that is upon us. But we are all workers in the most blessed and mundane sense of the word, and as workers we need protection.”

What does it mean to consider labor organizing as a form of caregiving, a way to love? Joining a union represents more than my own individual benefits: even more, it shows a devotion to my profession and to others who have committed themselves to the same work. As of the publication of this story, the whole editorial team at Burnaway is unionized under UAW 1981. This magazine remains committed to paying writers and artists fairly, supporting and elevating art and artists in the South, and contributing to an ecosystem that is sustainable and robust, allowing those who wish to remain in the South to do so. As musician and poet Gil Scott-Heron said in a recording released in 2009, “Someone’s always got to be on the job, because there’s always a job to do.”

This is the final installment in our collaborative series with Scalawag exploring art and labor in the South. Read Ben Beckett’s essay on museum workers’ unionization efforts and the history of right-to-work laws in the South here.