Music videos projected onto nineteenth century ruins explored the theme of “paradigm shifts.”1 Watching the films, I noticed how the videos interacted with the texture of the brick, glimpsed the sky beyond the wall, and felt the humid night. Considering both screen and space, I wondered, “What is coming to an end in our world today?”

the end is near, the end is the beginning was an installation of video art by women of African descent held as part of SITE at the Goat Farm during Atlanta Art Week from Oct 5-6. Organized by Lauren Tate Baeza, the installation comprised Songs for the End of the World (2024), a collection of new music videos by Nigerian filmmaker Zina Saro-Wiwa, the two-channel video Gathering (2024) by Atlanta artists Charmaine Minniefield and Kimberly Binns, and the film Kambule (2022) by Maya Cozier.

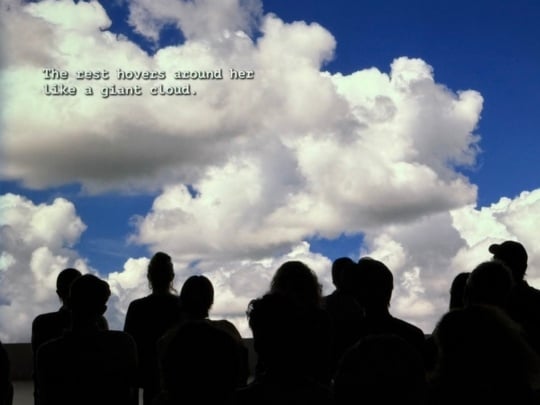

As Baeza wrote, “Songs for the End of the World tackles the weight of apocalypse with carefully curated songs […] exploring the emotional experience of finality.”2 The videos played on one side of the complex while the films on the other side paused, an apt curatorial decision enabling the audience to view the works in their entirety rather than grasping fragments through intermittent viewing. Moving from one projection to the other, the audience’s journey echoed the movement captured in the films, for example, dancing in Saro-Wiwa’s video Cosmic Shebeen (2024).

The four-minute Cosmic Shebeen cuts between three sequences. In one, a beautiful Black woman in a fur coat drives from a gas station to the desert, where she sways serenely, communing with the wind as it ruffles her fur. Dressed in black feathers, a masked “Angel of Death” haunts the woman.3 This figure is revealed as Saro-Wiwa, who in another sequence woven through the video delivers the song’s lyrics with the assured affect of a rapper. In a third sequence, a trio of muscular men perform a choreography that evokes a sense of militant resistance. Bobbing their heads, crossing their arms, and stomping their legs in unison to the song’s driving rhythm, they aim their pointed gaze at the camera.

Saro-Wiwa’s previous work Karikpo Pipeline (2015) also features sinewy men who perform masquerades on abandoned oil pipes in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria, where Saro-Wiwa was born. Western oil companies have devastated the Niger Delta with reckless drilling practices. While images of the region often overemphasize this destruction, Saro-Wiwa’s practice aims at representing the area in subtler ways that imagine repair. In Cosmic Shebeen, the elegant woman, representing capitalist consumption, forsakes oil and its corrupt economics to discover a renewed relationship with the earth. Later, the men dance at the gas station, communicating victory over foreign plundering of the local oil. The video epitomizes the installation’s theme of apocalypse through its visualization of the end of exploitative extraction.

In Time Is Not Enough, another standout video in the installation, a bird, rendered in stunning digital animation, rises from a deathbed, symbolizing the spirit of the artist’s mother. Her father, Ken Saro-Wiwa, is the noted environmental activist who was assassinated for his staunch resistance to the degradation of the Niger Delta. This video meaningfully draws attention to Maria Saro-Wiwa, a teacher, whose recent death the filmmaker vulnerably mourns over a plaintive guitar. Animation enables the representation of the incommunicable transition from the physical to the spiritual realm. The music references healing—the internal metamorphosis that loss requires. Indeed, Saro-Wiwa aims to “[leverage] pain and grief into something transformational.”4

Due to technical issues on the first night of the installation, the videos glitched early in the evening. Technology was at once the artists’ material, a tool for displaying the films, and an impediment to viewing. The conflict between the intention to screen the films and the involved logistics paralleled the negotiation that the audience performed in navigating the constant stream of SITE attendees. But this grounded the spectator more deeply in their body, allowing for responses to the films less feasible in theaters or galleries, permitting them to process the work through conversation or dancing.

Indeed, Cosmic Shebeen inspired a few audience members to two-step. The glitch offered a pause in which one could digest what they had seen, decide where to go next, or ask questions. As Legacy Russell writes in Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto, “[T]he glitch creates a fissure within which new possibilities of being and becoming manifest… [It] generates a welcome and protected space in which to innovate and experiment.”5 Thinking about the glitch made me embrace the vicissitudes of technology as part of the work, just as Baeza’s curatorial approach prompted the viewer to consider screen and space as part of the films’ exploration of deaths real and metaphorical. With its site-specificity, content, and unexpected moments, the installation launched new understandings of works that grapple with the end.

[1] Lauren Tate Baeza (organizer). Interview with the author, October 9, 2024.

[2] Lauren Tate Baeza. 2024. “Descriptions and Credits: the end is near.” PDF, October 8, 2024.

[3] Lauren Tate Baeza (organizer). Interview with the author, October 9, 2024.

[4] Lauren Tate Baeza. 2024. “Descriptions and Credits: the end is near.” PDF, October 8, 2024.

[5] Legacy Russell, Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto (New York: Verso Books, 2020), pp. 13-15.