Kara Walker’s 8 Possible Beginnings or: The Creation of African-America, a Moving Picture (2005), a grainy black-and-white film, unfolds in shaky, animated-by-hand silhouettes. At a crucial juncture, the figure of a well-muscled African-American male, presumably a slave, is impregnated by a besuited, presumably white plantation (and slave) owner, who delicately inserts a single cotton boll up the slave’s ass, who in turn gives birth to a phallic abstraction – an unformed fetal figure, an amorphous tar baby that further morphs into a tree from which lynched black bodies hang.

Walker’s work of incendiary eroticism is one of a kaleidoscopic array of some 60 artists responding to or in some way channeling the American South in “Southern Accent: Seeking the American South in Contemporary Art,” a joint curatorial venture between the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University and the Speed Art Museum in Louisville. The hallucinatory quality of Walker’s work is in keeping with the tone of the exhibition. Co-curators Trevor Schoonmaker of the Nasher and Miranda Lash of the Speed have opted for an almost surrealistic approach to the question of regional identity, which is a good thing. The anticipatory tension at the prospect of strict or literal delineations is met with exuberant problematizing.

Despite its halluncinatory tenor, the exhibition does not let us off the hook. From one work to the next, the viewer may be subject to a sense of overwhelm and emotional triggering. The construct of the American South serves a kind of metonymic function for a particular brand of racism and a slew of other cultural exports that have been absorbed and integrated into mythologies and distortions that extend far beyond the Mason Dixon line. Cumulatively, the works in the exhibition forge an approximation of Richard J. Powell’s succinct assessment in the exhibition catalogue of the historical and cultural factors that shaped the South: “from its genesis and growth as a result of agricultural prowess and the transatlantic slave trade, to its identity being irrevocably tied to the American Civil War and that conflict’s bloody legacy of racial discrimination, and more than a century of struggle over extending citizenship to its African-American populations.” The idea of The South in these terms has dire stakes in the current moment: the very fact that there is a need to assert that Black Lives Matter is rooted in this legacy.

But at its core, “Southern Accent” refuses to establish definitive boundaries. The works give rise to both recognition and revelation, sometimes simultaneously. The experience of the exhibition is one of having entered into a series of unfolding Venn diagrams in which congruent and overlapping themes arise and fade, never allowing the viewer to draw precise conclusions or derive static terms. This substantial exhibition features over a hundred works in a range of mediums that include painting, drawing, sculpture, installation, performance, photography, and video. The works in the exhibition are filtered through a lens of diversity by both national and international artists, each of whom represents a particular faceted relationship to the show’s premise. The thematic reach of the exhibition extends along a wild range of interrelated themes that accrue to the American South, from cuisine to climate to flora, fauna, poverty, privilege, subjectivity, identity, ethnicity, religion, music, sexuality and a range of symbologies, punctuated by flags, both American and Confederate.

Black Flag (For Elizabeth’s), 2008, by Skylar Fein (b. Manhattan, lives in New Orleans) is a large construction of wood, plaster and acrylic. Its formal orientation is the American flag, but it is rendered in black and white with punches of red and yellow and painted up to resemble a wall menu in a New Orleans snack shack. The signage advertises Creole delicacies such as “dream burger w/ praline bacon & blue cheese,” “smoked crispy hog jowls,” and “Beer-B-Q oysters” peppered with salient adjectives, “ripe,” “sweet,” “boiled,” “tail-on” and, singularly, the word “yes.” The work serves up a conceptual gumbo of punk rock anarchy and cultural/culinary appropriation as well as oblique homage to Jasper Johns and Andy Warhol. The strategy of the conceptual and cultural mashup serves as a cornerstone of the show. [cont.]

[cont.]

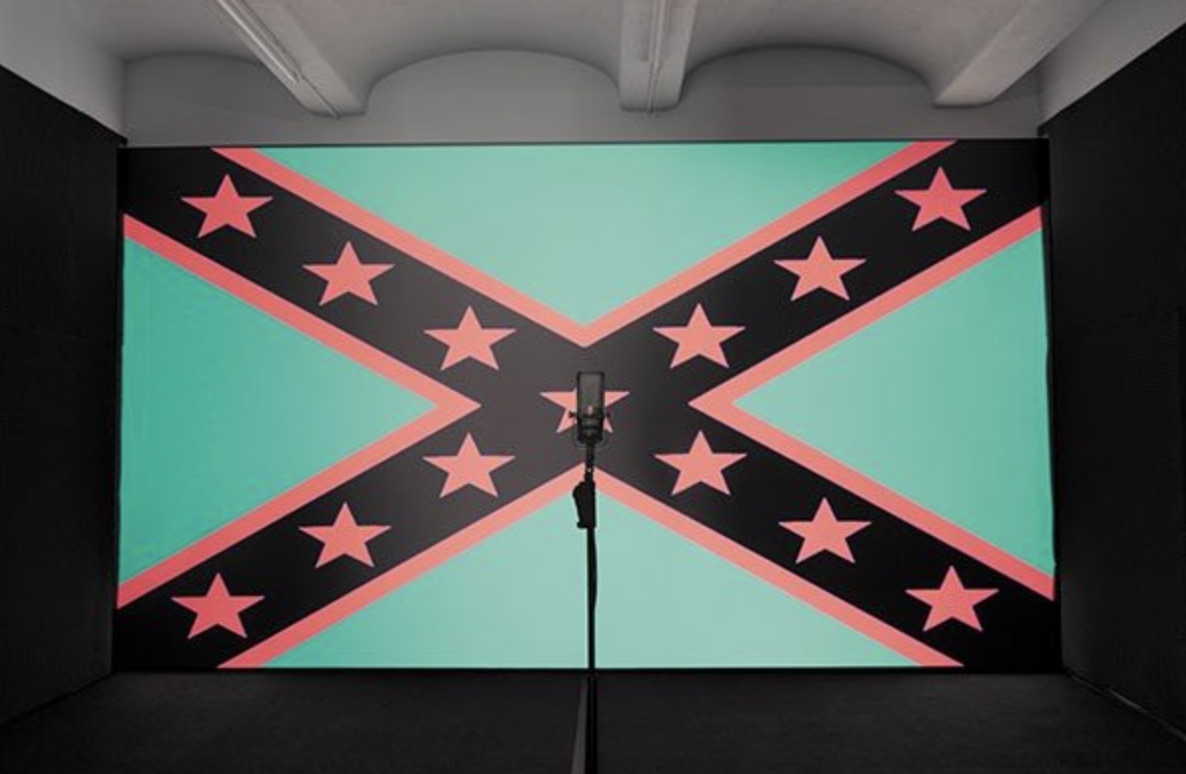

New York artist Hank Willis Thomas’s Black Righteous Space (Southern Edition) (2012/2016) is an immersive project, a black viewing room with a hyped-up Day-Glo animation in which swirling, morphing designs never coalesce but ultimately reveal themselves as constituent parts of the Confederate flag, subversively set forth in the colors of Pan-African liberation (red, black and green). The animation is accompanied by a soundtrack that includes songs, speeches, and dialogue by black leaders. A live microphone is centrally positioned, which activates the space as a zone of agency and articulation.

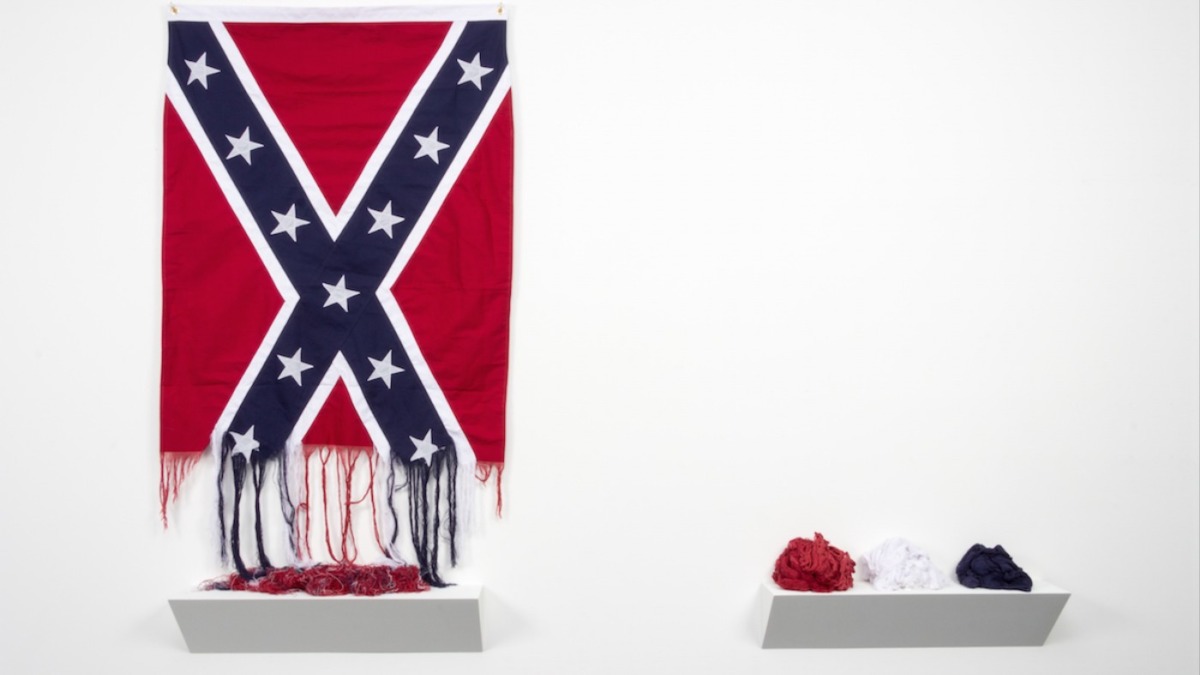

The Confederate flag is also given interactive treatment in Sonya Clark’s Unraveling, in which the public is invited to join the Richmond-based artist in the careful and painstaking work of dismantling a Confederate flag thread by thread. This contemplative collective action serves as an almost meditative act of protest and critique. In an interview on the exhibition page, the Richmond-based artist explains, “Unless you study textiles, you don’t understand that much about them.” (Ani Albers engaged in studious acts of “un-weaving” at Black Mountain for the same reason.) The work operates on multiple levels, decelerating temporal experience in an ADD era and allowing for the semantics of the gesture to be gradually revealed. At one point during an interview the artist acknowledges in the most understated way that the action of the work can also be seen as a form of “cotton picking.”

While there are multiple conceptual entry points to the exhibition, its two literal entry points are marked by sculptural works that flank the entrance to each of the two major sections – one by Theaster Gates (Chicago-born and -based) and the other by Alabama’s Thornton Dial. The two works serve as generational and thematic markers. Gates’s Soul Food Rickshaw for Collard Greens and Whiskey (2012), a hybrid form that features vintage desk drawers on wheels, functions like a thought experiment made tangible. The structure emblematizes the bearing of a burden – a functionally intersubjective condition whereby one person draws upon the physical strength of another. The structure denotes an inherently unbalanced power equation, in which one person exerts mightily while the other reclines and yet is moved forward, one of oppression and exploitation, in which the (privileged) person is borne upon the back of the (oppressed) other. However, Soul Food Rickshaw is complicated by its purported intention – and that which is borne upon it is not another person but a particularly Southern mode of nurture and sustenance.

Vital questions of scale and monumentality are raised in Dial’s Monument to the Minds of the Little Negro Steelworkers, 2001–03, in which roughly forged steel rods are spun and twisted into decorative curlicues and embellished with found materials that include wire, twine, faded artificial flowers, an old ax blade, glass bottles, the desiccated skeletal remains of animals, distressed swaths of vintage cloth, rusted tin cans and paint-can lids. Dial himself had been a steelworker, and the celebratory expressive lines of the steel work suggest a quality of freedom and self-assertion in an unforgiving medium. The structure carries both dark and light associations, from garden fences to prison bars. The found materials serve as traces of life and markers of death. [cont.]

Several works in “Southern Accent” traffic in such a mode of material alchemy. In Atlanta native Radcliffe Bailey’s Up From (2015), a black head in a top hat is perched deftly upon a hunk of whitish stone and seems to hover just in front of a wall-hung canvas tarpaulin painted over in rum and Georgia clay, subtly embroidered with symbolic forms that span African and African-American cultures. The scale of this floor-to-ceiling work generates a vortex of intensity and envelops the viewer in its earthen and ochre tones, subjecting one to palpable tension in anticipation of imminent magical intervention given the work’s invocation of the Yoruba trickster-deity Eshu and Haitian veve (Vodou symbols used to commune with the spirit realm).

Southern Hospitality (2010) by Sam Durant (b. Seattle, lives in L.A.) hinges on its own precise, stark material terms. Crucially, the work has no pedestal and consists of a gray military blanket folded neatly on the floor (inevitably invoking the work of Joseph Beuys), upon which is placed a single unopened bottle of Southern Comfort whiskey and a pristine ax handle. It is notable that no photography of this work is allowed, which, given that so many of us now mediate our own experience through picture-taking, seems to underscore its directness, and its unmediated and immediate confluence of violence and solace.

Other materially charged works include San Antonio artist Dario Robleto’s A Defeated Soldier Wishes to Walk His Daughter Down the Wedding Aisle (2004), in which surreal, disembodied military boots appear to march along a path of white rice powder in a sparse but conceptually elaborate reliquary construction. Suspended in one of the gallery spaces is Jeffrey Gibson’s “I PUT A SPELL ON YOU” (2015), a poetic conflation, an artifact redolent of an oppressive sport in the form of a repurposed punching bag ornately beaded in homage to the artist’s Cherokee/Choctaw heritage to spell out the title of that haunting song. Mel Chin’s Terrapene Carolina (Hillbilly Armor), 2005, is a massive sculptural assemblage of Appalachian detritus, including an old shopping cart, roofing material, a window frame painted pink, tar paper, and a crushed TV antenna. The work is an invocation of the material deficits suffered by American soldiers in Iraq who are forced to up-armor their Humvees with junk.

The exhibition features two works by Warhol, a signature treatment of Dolly Parton (1985) and Birmingham Race Riot (1964). Birmingham is a reminder that Warhol’s project was always a socially critical one, while Dolly, which bears a resemblance to Warhol’s self portraits in drag, opens up a space for a queer reading of Warhol with a particular Southern twang. Two large-scale color photographs from Catherine Opie’s Domestic series feature lesbian couples in the South in 1998. The L.A. artist’s works shine a light on the contemporary queer American South, subverting hetero-normative paradigms of domestic bliss, offering complex images of everyday life and less visible forms of intimacy and cohabitation. Another perspective is that of Roger Brown’s diagrammatic oil painting Kissin’ Cousins (1999), whose visual style skews toward decorative market murals and hand-painted signage. The work traces the Alabama-born artist’s own family tree alongside that of Elvis Presley, a claim of genetic closeness that fuels the frisson of the man and the myth, a highly specific homoerotic fantasy whereby just the right amount of familial distance is present in the lineage to sanction sexual intimacy (ergo, “kissing cousins”) – a deep irony given the lamentably still-current prohibition against same-sex erotic expression in the South and elsewhere. [cont.]

Stacy Lynn Waddell’s belle (2010), a burned imprint on paper overlaid with silver leaf, is a palimpsest of layered meanings. The work depicts the bust of a finely dressed Civil War-era woman of means, whose head is covered with a bell, which according to the wall label is based on one found in the “wreckage of the British trade ship Henrietta Marie, which sunk off Florida’s coast in 1700,” a vessel that bore human cargo in its hull. The use of the lower-case “B” in the work’s title underscores the lack of a proper name. Through a grammatical operation, the person is recast as an object, a functional commodity, stripped of her/its humanity, her/its human “being.” The elided person is nameless and faceless – the “who” is transposed as an “it.” The bell that covers the head suppresses it as a site of mind and consciousness. The North Carolina artist’s chosen modes of production, burning/branding and the laying of silver leaf are equally loaded actions. Branding evokes the coercive violence of human ownership. The application of silver leaf reverberates with illuminated manuscripts and high ornament. It also draws parallels with high modernism, monochromatic minimalism, Warhol’s signature metallic silver works and the mirror’s recursive reflection of the self.

Strange Fruitz (2013) is a mixed-media wall-hanging on paper by Jamaican artist Ebony G. Patterson. The piece beckons with its shimmering synthetic red, a luminous red of the same Technicolor hue as Dorothy’s ruby slippers in 1939’s Wizard of Oz – the same year in which Billie Holiday’s haunting dirgelike song (Strange Fruit) was released. The song was based on a poem by Lewis Allen, which was based on Lawrence Beitler’s indelible 1930 photograph of the lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith in Marion, Indiana. The piece holds space like a tapestry – with an almost ornamental quality. Then one notices that what appear to be vines or branches hanging down from the top edge are dangling legs, some shoeless, some in fashionable footwear. The precise scalloped pattern along the work’s bottom edge first scans as decorative, but as the full import of the work comes into focus one recognizes the pattern as dripping blood.

Jessica Ingram’s 2006 series Road Through Midnight: A Civil Rights Memorial is founded upon a principle of the evidentiary site, framing banal locations – a gated area on a mountaintop in Georgia, the red doors and the red and green window frames of a law office in Tennessee, wildflowers in full bloom near an empty field and tall trees encircling a swamp in Mississippi – as flash-points, loci of racial injustice, violence and murder. In some respect, Ingram’s photographs function like the spontaneous wreaths and offerings that are left at locations of annihilation and loss. They are composite images of beauty and banality; they establish a sense of place – and they require the conscious engagement of the viewer for their meaning and function to be fulfilled.

Despite the contemporaneity of Deborah Luster’s photography, her choice to render the scenes in black-and-white pushes a sense of memory that defies nostalgia but nevertheless triggers associations of the past. This sense is underscored by the fact that Luster’s subjects in the two large-scale works on view are children. Septima with Tadpoles from the Lost Roads Project (1993), a gelatin silver print, is a ground-level shot of the bare feet of a young girl in the woods, wild grasses underfoot. Barely touching the child’s toes is a large Mason jar filled with milky water and squirming black tadpoles. The light hits the water in such a way that it appears to glow, the active larval forms wriggle with new life. It is a highly specific childhood memory, the bare feet on grass, the dense woods filling the pictorial frame, the patchwork of light and sky through the leaves, the child’s delicate white lace dress. The precise terms of the composition allow us access to a particular rural Southern experience that hovers somewhere between gritty truth and literary imagination.

Burk Uzzle’s Acid Park (2009) conveys a heightened surreal atmosphere. The title of the work is the name conferred by locals upon a particular spot in Wilson, North Carolina, the site of Vollis Simpson’s renowned makeshift whirligigs. The self-taught artist took functional objects — fans, cogs, vents and whimsical metal cutouts — and repurposed them as sculptural wind turbines, some as tall as a telephone pole. In Uzzle’s image, mist hangs heavily at the idiosyncratic site, which constitutes a uniquely Southern geomancy and foregrounds the relationship between place and personal/cultural identity. The park’s name and trippy quality of the image suggests a place with the capacity to induce a hallucinatory state – or one that might serve as an ideal spot for the ingestion of mind-altering substances – DIY shamanism.

The hallucinatory tone of “Southern Accent” casts a patina of strangeness on works that in other contexts might read in more direct ways. This becomes a productive challenge when viewing the photographs in the exhibition, many of which already push strangeness in the familiar, including major works by William Eggleston, William Christenberry, Carrie Mae Weems, Sally Mann, Richard Misrach, Jeff Whetstone, and others.

Regardless of curatorial strategy, one might ask whether the question of regional identity is valid as the basis for an exhibition in an era of corporatized cultural homogeneity, at a time when the dominant perceptual experience of life online is a conflated one in which global art and culture are reduced to data, delivered to all points in uniform streams. On some level, in an exhibition that presents the question of regional identity, the works become subservient to the whole, they are posited as fragments, puzzle pieces. At times, one must prod one’s own psyche and remind oneself that the works are not components of a single organism – they exist on their own without being hooked up to the life support system of the exhibition concept. They are autonomous and therefore subject to a lifetime of alternate readings and ever-shifting meanings wholly unrelated to the exhibition’s premise.

However, given its depth and resonance and its sense of abundant aesthetic activity, which is clearly reflective of a specific Southern-inflected impulse in contemporary art, “Southern Accent” comes back with a resounding reply in the affirmative – convincingly making its case for the vibrant engagement of a significant and broad range of artists who mine and/or reflect the American South – to far-reaching different ends and purposes – but which nevertheless merits an exhibition of this scope and scale.

Southern Accent: Seeking the American South in Contemporary Art” is on view at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, through January 8, 2017. It will be on view at the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Kentucky, April 29-August 20, 2017.