Shara Hughes paints with a mean “intra-subjectivism,” a rejected appellation attempted by Museum of Modern Art director Alfred Barr to describe the group of painters who became known as the Abstract Expressionists. “Guess You Had to Be There,” her current exhibition for the Working Artist Project at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia, prioritizes spontaneity of gesture, giving a nod to the expressionist trust in paint’s ability to attain natural equilibrium of concept and form. Fast-moving paint washes are asserted alongside globs, sprays, and scumbles with equal intensity and success. Pictorial space emerges from a sharp, sumptuous, and unrelenting investigation of paint. Discordant color combinations buzz with tension. Improvised figures are woven into narratives that are reinforced by the artist’s frank hand and easy assertion of depth.

Hughes’s paintings have evolved since the artist graduated from RISD in 2004. Formerly, domestic interiors dominated her subject matter, but they soon began to display her emergent sense of psychology and a fascination with diverse methods of paint application and texture. Bucking the prevailing wisdom that an artist must be in New York to succeed, she has attained an international reputation and is adored in her native Atlanta, having had two solo museum exhibitions in rapid succession—this show and last year’s “Don’t Tell Anyone But …” at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center. With Ben Steele, she also co-organizes Seek ATL, a studio-visit program that promotes dialogue in the Atlanta art community.

In these new works, the fragmentary assembly of painted passages melds well with an interrupted and occluded cast of characters. The slippery and emotive psychology of the painting’s characters, judging from their intimate and sometimes violent interplay, is aptly conveyed through shifting narrative sequences. Non-continuous horizons and spatial perspectives allow the viewer to see through a prism of pure feeling. Psychology oozes from the paintings and, sometimes, the bright and snappy presentation accommodates characters that interact with a benign violence.

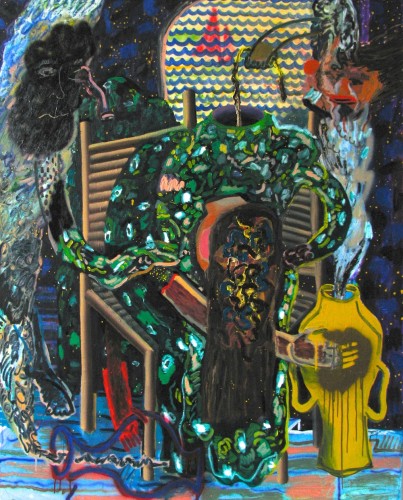

Despite her works’ openness to interpretation, Little Help Here? is clearly a scene of decapitation. Clothed in an emerald green patterned frock, a central seated figure holds her head in her lap while spirit-like presences prod and pour things into her stump. Part of her body is writhing in pain while her torso remains erect. Also visible are a lamp, a menacing shaded face, a pipe, and a foot.

The Juggler features a similarly gruesome cast of characters in the fashion of Thomas Eakins’s The Gross Clinic, but here a cadaver is sprouting flowers, the table has morphed into a beach ball and a grizzly stoner floats overhead. Hughes depicts props that represent psychic stress and are more or less symbolic of sex: boxes, vessels, fruits.

My Hero is less figurative. Arms grow out of the center of the composition—they almost blow in the wind. It’s not clear how the landscape, painted in green and brown, is supposed to be construed apart from the actions of limbs, but the similarity of form between the arcing arms and landscape adds a coherence to the composition. The painting simultaneously feels erratic because of its psychological cues and orderly because of the well-organized internal components of composition. Lushly articulated elements stand out. A sliver of sprayed yellow and black canvas shines, as does a pair of stippled orbs floating along the right side. Here, a beach ball floats in the upper left corner. Hughes mobilizes a slew of tricks, painterly applications that fix together the deliberate gesture and the conceptually distinct accident in a manner resembling a little thing we might call daily existence.

Spatially, several paintings depart from the set. Let’s Grow Up Together is a somewhat drier painting with obvious art historical references. A cohesive fluorescent palette contrasts with a dark brown floor. However electrifying, the push-pull is disorienting and resists stasis. A maelstrom of Matissean patches frenetically crawls in place and prevents the figures from advancing into the foreground.

Many Moons mixes a vertical oblique perspective with a mental space. Again, an airy environment and a deftness of touch that a Shoalin monk would envy betray a darker subtext. David Hockney and Tal R come to mind—both use rudimentary flattening and couch moody content into childlike depictions. Vertical side bands frame two horizontally oriented landscapes. The bands read almost as scrolls. The flat presentation and repeated round forms convey a menacing simplicity, like an imagined child drawing with a single repeated icon instead of syntax. Ice-cream-colored hills flatten out, mimicking a darkened field of red situated beneath it. A stretched and distorted moon complements side moons that bring to mind Haruki Murakami’s novel IQ84. In Murakami’s narrative, two lovers cross paths in grade school and form a lasting bond. Separated by the contingency of their lived lives, the characters decide independently to find each other after years of separation. They end up in a parallel existence on an Earth with two moons and discover that reuniting means one of them must die, a powerful parable for the difficult nature of love.

Whether the painting represents the passing of time (it’s been many moons since …) or parallel universes, it definitely stands in for a conflicted consciousness. Hughes’s confidence in the fluidity and corresponding unwieldiness of painting and her ability to coax effects from it manifests a pictorial series of deep contradiction, but perfectly describes a real world where opposites attract and opposition forms the basis of intense attraction, and sometimes repulsion.

“Shara Hughes: Guess You Had To Be There” is on view at MOCA GA through June 28.

Disclosure: Shara Hughes is BURNAWAY‘s Outreach Coordinator. In pursuit of featuring work that significantly contributes to cultural discourse, as well as our commitment to transparency, our policy is to disclose instead of exclude.