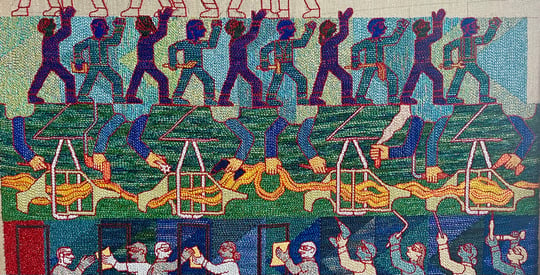

That Rashaad Newsome should choose to take on Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is so perfect. In Look Back at It (2016), all of the figures from Picasso’s painting are replicated, but in collages made up of black bodies, fireballs, and bling. The logic of Newsome’s collage technique draws upon the fragmentation of the body that Picasso popularized, calling out the long tradition of T&A from modernist painting to rap videos and advertising. In the 1907 painting, Picasso famously used African masks for the faces of two figures—borrowing from a culture then considered ‘primitive’ in order to buttress his own artistic rebellion. In Look Back at It (2016), Newsome responds to the white male privilege of primitivism by using photographs of actual African masks. The figure squatting in the lower right corner of Picasso’s painting—legs spread wide in what has been interpreted as sexual availability for a brothel customer—has been replaced by one with long curly hair colored pastel pink, an ass made out of jewels, and a pair of black stilettos at the end of rhinestoned, caterpillar legs. This monstrous figure has an African mask for a face, and she is twerking.

Look Back at It (2016), the homage to Picasso, is the star of the eleven collages featured in “Rashaad Newsome: Mélange” at the Contemporary Arts Center in New Orleans, an exhibition that also includes several prints and videos that explore the vogue dance tradition. The CAC show is a second homecoming for Newsome, who grew up in New Orleans. His first homecoming was the 2013 exhibition “King of Arms” at the New Orleans Museum of Art. That exhibition took advantage of the museum’s permanent collection to draw parallels between the iconography of hip-hop culture and expressions of status in Baroque and Rococo art. Bling is bling no matter what period you’re dealing with, a point made by the pairing of Newsome’s video Herald with the museum’s gigantic portrait of Marie Antoinette.

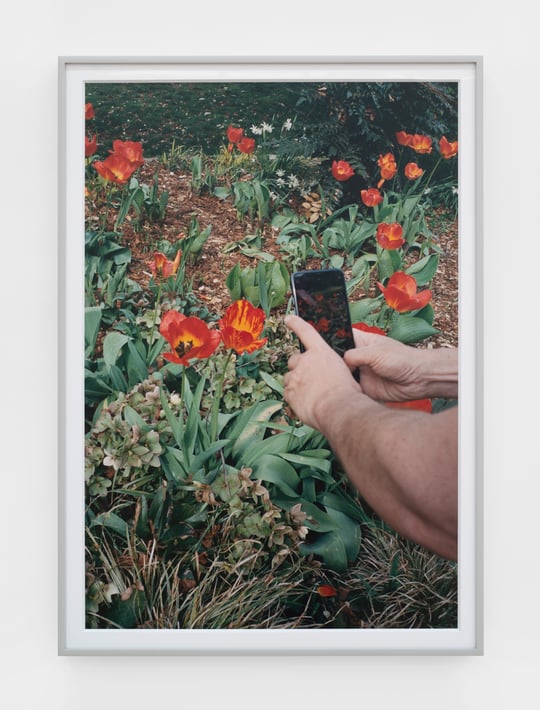

The bling in these new collages comes from advertisements for high end jewelry and clothing but also from “men’s magazines” like KING and Black Lingerie. Wanting to subvert the misogynist gaze of these images, Newsome cuts them apart and reconstructs them into zombie forms that seem to empty out their original references. Girl Bye (2016) gives us a glimpse of one body before its fragmentation. The figure’s perfect smile becomes a little creepy when placed underneath a screaming, collaged head with only one eye and fireball hair. The collage even has pieces that mimic the dripping style of Abstract Expressionism—after all, Willem de Kooning’s Woman series started with a red lipsticked-mouth cut from an advertisement. But Newsome’s allies are female: Hannah Höch in the Dada movement, or more recently, Wangechi Mutu.

34 by 29 inches.

Some of Newsome’s titles provide laugh-out-loud moments. When You Get Your Hair Done for the Family Barbecue and You Know it Looks Good (2015) features a face with a fireball hairdo, and she does look good. Newsome brings depth to the collages by differentiating multiple visual planes, causing them to almost appear as if they are relief sculptures. Each collage is set in a shadowbox frame to accommodate and emphasize its objectness , and several have custom frames that are inspired by car culture. Colored glitter sparkles from the black glossy coating used for the frame of Look Back at It, while others alternate between chain-link belt patterns and embossed leather frames.

Another strategy for subverting the gaze is to refuse the fetishization of the female silhouette. Most of the collages isolate one complex shape against a black field—a blackness that conceptually represents ideas of racial identity. The silhouette of each collage’s central figure was derived from stills of vogue performances.

A large part of the exhibition space has been devoted to the video FIVE SFMOMA (2017), based on a performance at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2012 (the same series was included in the 2010 Whitney Biennial). The format of the Five series breaks down the genre of vogue femme, considered a subset of vogue performance, as if for examination. Five dancers demonstrate the five basic moves associated with vogue femme: hands, cat-walk, floor performance, spin dips, and duck-walk (for a dictionary of vogue terms, including these, see here). Two silent videos, Untitled (2008) and Untitled (New Way) (2009), installed behind Five at the CAC show how the different moves are combined in practice.

The phenomenon of voguing entered mainstream culture through Madonna’s 1990 song “Vogue” and its iconic music video, now remembered as notorious instances of cultural appropriation. Madonna worked with choreographer Willie Ninja, who had been featured in Jennie Livingston’s 1990 film Paris is Burning, a documentary about the Harlem origin of vogue culture. Paris is Burning takes us into a subculture where queer men and trans women, often of color, dressed in gender-based roles and stereotypes so perfectly that they could pass undetected in public. The vogue culture depicted in Paris is Burning treated these cross-dressing performances as competitive events along the lines of ballroom dancing, graded by judges who hold up scorecards to assess each performer.

Drawn from her own critical study of drag culture in the late 1980s, Judith Butler’s theory that gender consists of social performance and has no natural basis in the body is now routinely accepted. Newsome emphasizes the artificiality of gender in our post-Butler world through his use of makeup and costumes—the neon-colored wigs are not trying to fool anyone.

Like the collages, the Five performances stage a clash of cultures. An MC and the vogue dancers represent queer club culture, while an opera singer represents the ideal of traditional high culture. The CAC presented two live performances of Five on January 20, titled Mélange (watch a clip here). Each iteration features site-specific music choices, and in New Orleans that means brass band music: a trumpet, sax, clarinet, and sousaphone. Each performer comes onto the stage as if walking a fashion runway, dances at the end of the runway right in front of the audience, and then walks offstage. The musicians improvise in response to the dancers, based on melodies that are worked out beforehand, while the MC narrates, scats, and responds to the dancers.

Newsome ‘conducts’ the performance, using a computer program that relies on motion capture to translate the dancers’ movements into differently colored lines projected on the wall behind them. The digital drawings are then turned into lithographs, five of which are on display in the gallery. Each print is named after the performer whose movement it depicts —a gesture that I wish had been extended to the video and performance, which did not credit the vogue dancers by name.

“Rashaad Newsome: Mélange.”

The performers’ athleticism and skill were astounding, and the sense of energy in the room was infectious. But this response raises its own questions about the force of bringing vogue into an institutional art space. Is the performance just a spectacle of titillation? Or can the institutional space be used to bring greater awareness and respect to vogue and its participants? Newsome relies on the authority of his insider status, insisting that he is not a “flâneur” here (his choice of words, in a diss on Baudelaire)—when he moved to New York, he lived in a collective house and participated in the balls. He is not using vogue in the way that Picasso used African art; Picasso lacked understanding of the culture from which he was drawing. But the audience may be enjoying the performance in a way that parallels Picasso’s flâneur-like trips to the Trocadero to see African art. This is where the drawings are crucial, because they empty out the fullness of the spectacle of the live performance. They demonstrate the force of abstraction—the same force that makes us forget that there are real bodies beneath those flashy photographs of fashion models.

and local musicians.

This is where bell hooks comes in—a writer and coiner of the term “white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.” In the documentary about her that Newsome chose for the exhibition programming, hooks talked about “blackness” as a “sign of transgression,” meaning that it communicates transgression without actually doing the work of real transgression. She cites white men who listen to hip-hop but don’t engage black culture—they consume the sign without living the life. But her example could just as easily have been Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

Newsome’s challenge is to figure out how to reverse that flattening, that emptying out of blackness. hooks insists that the emptied signifier of blackness has a function: “[It] allows whiteness to remain static, to remain conservative, and its conservative thrust to go unnoticed.” She was speaking in 1997, and yet her discussion of how this dynamic coincides with “a mounting fascism in the United States” could not be more fitting now. Hearing that remark on the day before Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, and watching the Mélange performance on the very night of Trump’s inauguration, cut to the bone. For that is our world now, and we need to know how to resist.

“Rashaad Newsome: Mélange” is on view at the Contemporary Arts Center in New Orleans through February 12.

Rebecca Lee Reynolds is an assistant professor in the department of fine arts at the University of New Orleans, where she teaches art history.