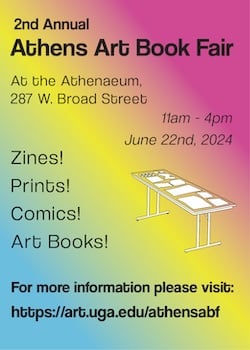

The title of The Hambidge Center’s recent exhibition, Fables of the Eco-Future curated by Lisa Alembik at Hambidge’s Weave Shed Gallery, gets right down to business [March 30-June 8, 2013]. Each word in that phrase weighs heavily with a sense of responsibility for shepherding history unto an anonymous group of people to come—stories, landscapes, and prophecies that must be delicately shuttled through time. The burdensome quality of such a title is fitting for The Hambidge Center’s 600-acre sanctuary environment in Rabun Gap, GA.

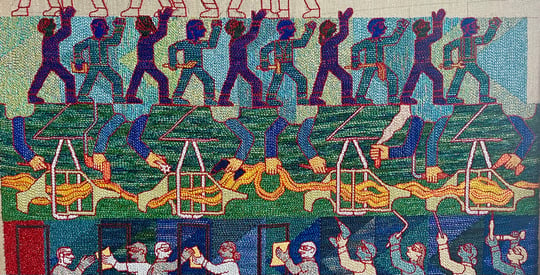

Three hours north of Atlanta and several miles from cell phone reception, Hambidge reserves the right to talk about an “eco-future.” That prefix has become increasingly commodified and consumer-driven since the turn of the millennium—seen more often printed across soap bottles in Target than discussed with sincerity. Several artists featured in Fables of the Eco-Future are former Hambidge residents. Curator Alembik states, “Some have preternatural abilities to predict concerns that will soon encroach on our horizons. They might envision an alternative future for the land, making plans and designing prosthetics for a new nature.” Their time spent in close proximity to nature as former residents at The Hambidge Center conjures an immediacy in these artists’s understanding of our shared environmental story. They eschew tropes about “our children’s children”—as politicians parrot—and unfounded apocalyptics to instead observe our current landscapes and viscerally ponder how they might develop over time.

The difference between an urban gallery and a gallery tucked away in the woods—even if they both exhibited the same ecologically-driven subject matter—can be reckoned through Gregory Byrd’s poem Dark Lesson in the written portion of Eco-Future. Illustrating the various personalities of darkness, Byrd writes:

It was the phosphorescence of pyrophyta

off a sailboat’s stern,

the whitish dusting of the Milky Way

from our dock. But in the city

there is no darkness

because everyone is afraid.

Byrd’s understanding of darkness as an entity that’s in-sync with a natural order, rather than its usual connotation as a synonym for evil and fear, reminds the reader that the modern relationship to nature is often backwards. Neither darkness nor light is preferred over one another in this poem, though the tendency to pit light against the dark in attempts to assuage fear causes discord in the established rhythm between the two.

Several of the works in Fables of the Eco-Future represent Byrd’s impression of a skewed, but not malicious, relationship between natural elements and people. For example, Marie Weaver’s ceramic statues of what could be viewed as prototypical Earth Mothers are instead surrounded by creatures and coated in swampy effluvia. By dementing their features slightly, Weaver removes them from the mythology of the nurturing mother figure. Weaver’s Gulf Greed slumps on a stump like a Venus of Willendorf who has long since lost her fertility, and whose maternal rotundity had been shed from working to clean an oil spill. Byrd’s other figure, Guardian of the Marsh, has the neck of a Modigliani and the vacant, placid features of the pleasantly insane. A halo of metal wire strings her forever to a series of birds; a frog sits in place the place her bosom would be.

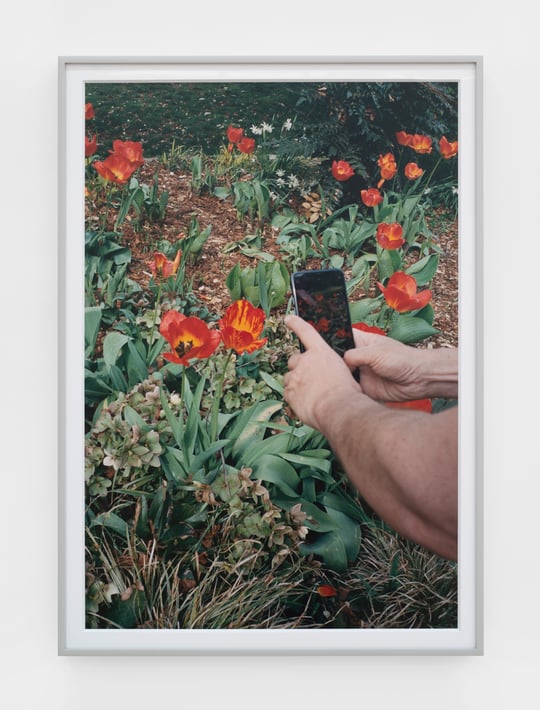

The feminine association with nature and fertility that Weaver plays with are allowed to sit out, ripen, and nearly go to seed in Diana Kingsley’s photographs. Her photographs [Principals & Partners, and Bohemian (2011)] read as high definition still lifes and reconcile the plump lewdness of fruit—like peaches and tomatoes—with their flinty stone and wood counterparts. Kingsley’s color palette of highly saturated reds and greens, coupled with rich earth tones and accented by inky black backsplashes, highlights the divergence of her ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ forms. The vintage subject matter, modern medium, and overload of color give these photos a psychedelic-baroque feel that’s refreshingly incongruous with the arts and crafts tendencies of much ecologically-geared artwork.

Kingsley’s ripe fruit reminds us that fertility, the promise of life, lies in limbo between morbidity and immortality. One’s natural role is to live, produce life, and die. While she successfully captures the moment between procreation and destruction, Allen Peterson’s work recreates the latent violence inherent to that cycle. His beeswax and wood sculptures Coevolution Study 4 and Hive Consciousness mimic beehives and call attention to creatures whose sole human associations are fertilizing flowers and inflicting harm. As the title Hive Consciousness nods, bees are unimpeachably faithful to their social order: They work to produce, procreate and serve their queen—a true Earth Mother in the sense that she’s more brutal than benevolent—from birth until death.

Each of Peterson’s sculptures feature a pale, bald human baby’s head already drained of life and protruding with honeycomb crystallizations that sit atop the man-made hive-bases (which resemble filing cabinets). The wax children are a product of nature (both conceptually and through material form), yet their production seems to rail against any romanticized notions of nature that modern culture has developed. For example, one of the babies nearly suffocates under the weight of the honeycombs, showing that the violence in nature’s cycle cannot be subjugated to efficiency; even honeybees lose their stingers to protect themselves and this kills them. Maybe Peterson means to suggest that the dreary cubicle life depicted in pop culture, such as the film Office Space, is the way people have evolved and, like the bees, we’ll keep doing it because that’s the way it works.

Eco-anything is a tricky matter because the discussion turns political so quickly. It devolves into what government policies would benefit societies the most, how we should compost, stop driving and go ‘veggie,’ and many overarching pseudo-philosophies about contemporary life. Artwork that falls in line with these hot topics reads like a self-help book, whereas works that provides a personal, complex perspective about the artist’s relationship with the environment echoes a novel. Hambidge provides a setting that fosters such a nuanced connection with a natural environment and, though Fables of the Eco-Future was not entirely immune to the pedantic side of ecological art, many of the artists were able to share work that spoke to that intimacy.

A full color catalog has been produced for the exhibition.

House rules for commenting:

1. Please use a full first name. We do not support hiding behind anonymity.

2. All comments on BURNAWAY are moderated. Please be patient—we’ll do our best to keep up, but sometimes it may take us a bit to get to all of them.

3. BURNAWAY reserves the right to refuse or reject comments.

4. We support critically engaged arguments (both positive and negative), but please don’t be a jerk, ok? Comments should never be personally offensive in nature.