Founded in 1993 to honor and preserve the history of Black Mountain College, the Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center (BMCM+AC) is not located in the North Carolina town its name suggests but in downtown Asheville, fifteen miles away. Having operated for twenty-seven years, the museum has already prevailed three years longer than the college it celebrates. Black Mountain College opened in 1933 with only twelve teachers and twenty-two students and, as is now well known, quickly attracted some of the most revolutionary artists of the twentieth century: John Cage and Merce Cunningham, Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly, Josef and Anni Albers. The institution survived only twenty-four years before closing its doors in 1957, its Lake Eden campus now a boys’ camp. Poet and potter M.C. Richards, a professor of literature at the college, captured this fugitive period by describing the school metaphorically as a female figure. She “was born in controversy and died in controversy, splendid in the between, as she inspired and shattered dreams of liberation and fulfillment. She lay on her side as the hills did across from Lake Eden, female in form. She hooted with the owls, and sat at peace with whatever her fate was to be.” Her fate, it seems, was an existence meteoric in its brightness and brevity, but her legacy—while augmented now by the museum’s mission—lives on through the school’s impact upon the ideas and the works of a generation.

Question Everything! The Women of Black Mountain College, on view through April 25 at the BMCM+AC, aims to illustrate this impact upon and by the women the school educated and employed. In the 1930s, 40s, and early 50s, amid a changing world, Black Mountain College provided a place where women could think critically, explore their self-determinacy, question the status quo, contribute. The exhibition takes its title from the ideas in a quote from alumna Mary Fitton Fiore (1949-1956), displayed as wall text at the entrance to the galleries: “Freedom. Freedom to walk barefoot, to wear old clothes… to have a sex life—but, beyond all that, to have a freedom the other side of which was (is) responsibility… a responsibility to listen to the inner voice and labor to follow one’s own deepest and truest desires, and a responsibility to give to, and not just take from, the school which made such choices possible.”

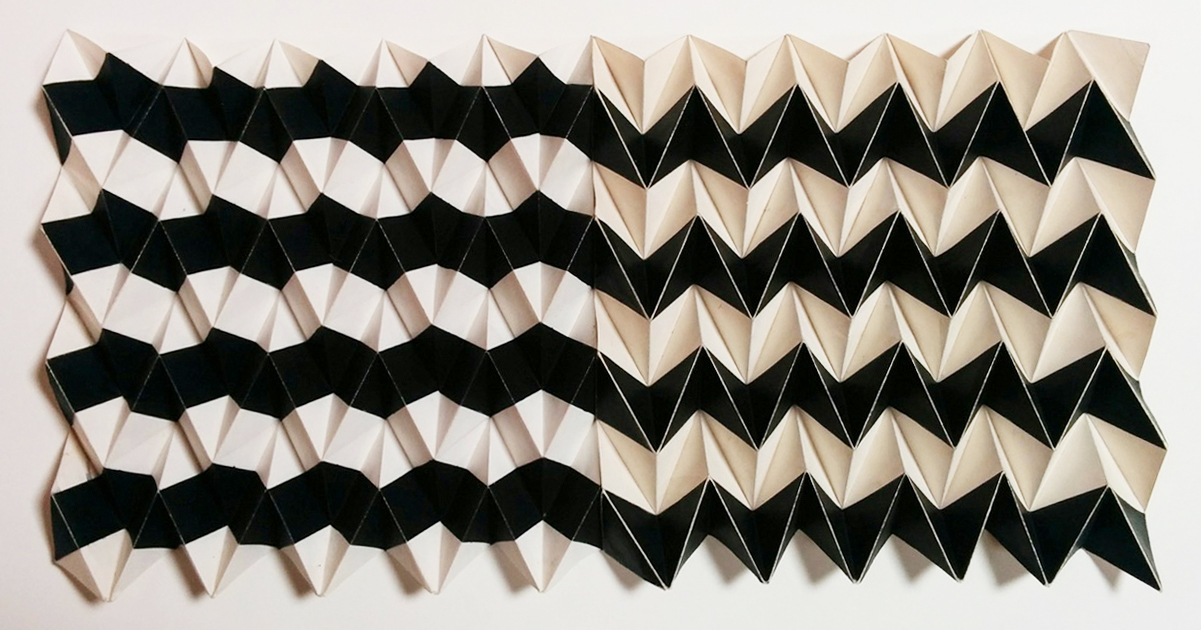

Black Mountain College was founded upon ideals of educational and intellectual freedom, and this is a show about the experience of that freedom. As such, it is therefore also a show about possibility and the art and progress that can be made when social strictures are loosened. Instead of advancing any sort of didactic message, the exhibition generally allows the art, along with other primary sources, to tell that story. The exhibition occupies both levels of a carefully renovated 1920s brick building, the former home of The Asheville Times. Upstairs on the main level, multifarious works—in wood, ceramic, drawing, painting, photography, sculpture, and fiber—are loosely grouped around such themes as “The Weaving Room” and “Craft and Design.” Selections primarily drawn from the museum’s permanent collection exist alongside surprising and impressive borrowed works, particularly a brilliant black and white, geometric form of folded paper loaned by the family of Ruth Asawa, who studied at the college for several years, and a drawing of Fairfield Porter by Elaine de Kooning, who visited when her husband came there to teach in the mid-40s.

There are well-known artists represented alongside those who are less well known, if not outright unknown (at least to this reviewer). Among the former, in addition to Asawa and de Kooning, are Pat Passlof, a student of Willem de Kooning (her Eighth House #18, on view here, clearly shows his influence), Dorothea Rockburne, and Susan Weil, who convinced her former husband, Robert Rauschenberg, to come to Black Mountain in the first place. There are surprises among the latter, including Diana Woelffer, a faculty spouse whose untitled gelatin silver print of a female nude calls to mind Harry Callahan’s (albeit superior) minimalist depictions of his wife Eleanor, and a playful mixed-media collage by Mary Parks Washington, a student of Hale Woodruff at Spelman College who became, in the summer of 1946, one of Black Mountain’s first African American students.

The women of Black Mountain College were students and professors, old and young, those who went on the wider acclaim and those who, well… didn’t. Capturing the interdisciplinary nature of the place, the exhibition shows painters acting, weavers painting, poets potting. The manifestation of these efforts reaches its apotheosis in the exhibition’s “Craft and Design” section. The tactility of craft and its presence in the gallery is the show’s strongest aspect. Sculptures in carved wood by Lorrie Goulet, a student of ceramics who studied painting and weaving with the Alberses while at Black Mountain, is a standout work in this section. Alchemical Form, a totem-like ceramic by M.C. Richards, a coil-built stoneware fireplace by potter-in-residence Karen Karnes, and, perhaps most especially, the elegantly sturdy wooden benches created by Molly Gregory, teacher of woodworking and furniture making, all more than hold their own against the best wire sculptures by Ruth Asawa.

The exhibition gives special attention to the contributions of Anni Albers, whose mark on the school rivals that of her husband Josef. Her workshop is brought to life by an original loom and beautifully woven fabrics—her own and others’—and further enlivened by The Weaver, painted on the original door to the Weaving Workshop and Art Room and retrieved when the school closed by alumna Faith Murray, who depicted its eponymous figure at work at a loom.

Materials displayed on the museum’s lower level revive the Black Mountain experience through archival photographs and documents illustrating social and academic life, classroom ephemera, and sketches and correspondences—most notably the letters of Ati Gropius, daughter of the Bauhaus architect Walter Gropius, who writes in one voice to her father and, amusingly if naturally, an entirely different one to a boyfriend.

Ultimately, it is not the quality of art on view that impacts the viewer but the cumulative story it tells, and more importantly, as the title suggests, the questions it raises. To what, or whom, does this particular mix of time and place and personality owe its enduring influence upon our collective imagination? Where is our Black Mountain? The films and oral histories included in the exhibition—especially the never-before-exhibited, newly restored archival films of Black Mountain instructor of photography Hazel Larsen Archer—warrant special attention. They exist as the only discovered moving image documentation of the college. Silently, they resurrect not only a fleeting time but the individuals who lived that splendid in the between.

Question Everything! The Women of Black Mountain College, curated by Kate Averett and Alice Sebrell, is on view at the Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center in Asheville, North Carolina, through April 25.