Nathaniel Donnett is a Houston-based cultural practitioner whose work is concerned with the psychology of Blackness, everyday aesthetics, and the multilayered, multisensory narratives present within them. Donnett’s work ranges from large-scale installations to two-dimensional works and audiovisual pieces that engage the visual culture and history of Houston, including Third Ward’s rowhouses, swangas on the S.L.A.B.S, and cruising down Houston’s roads. Donnett is currently a scholar in residence at the University of Houston Cynthia Woods Mitchell Center for the Arts, where we met in his studio on campus to discuss his origins in music, Houston’s Third Ward, and the ingenuity of Blackness.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

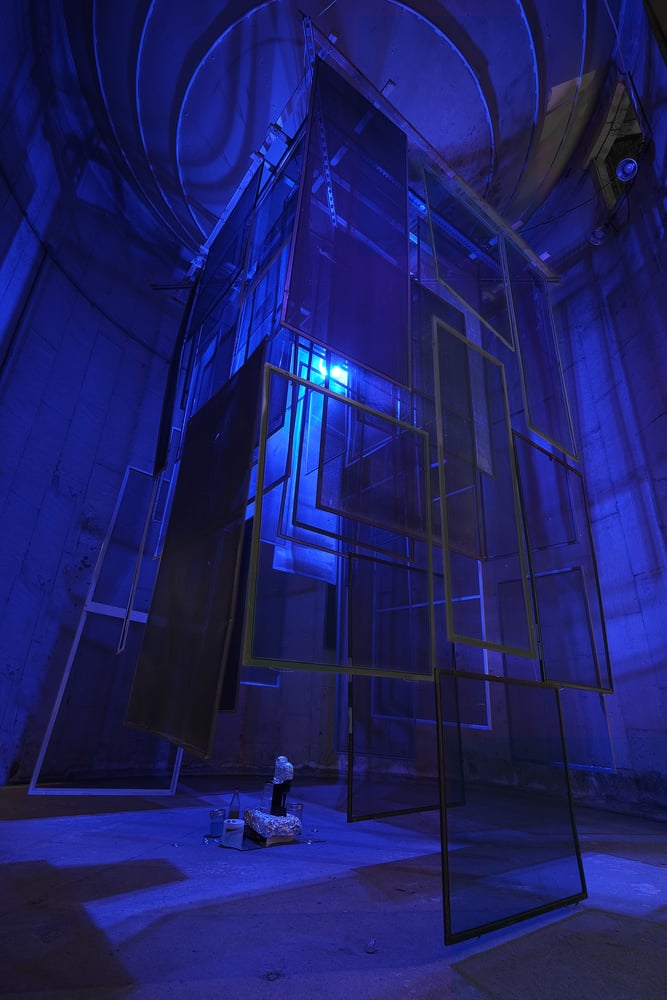

Zahrah Butler: Thinking about the open-ended, abstract nature of “Dark Imaginarence,” why not focus on a singular artistic medium, such as just painting or sculpting?

Nathaniel Donnett: There are many ways to say a thing. I look at the work as [I look at] life, very complicated and made of different components. Participating in these different disciplines is the way to get to the peak humanness of aesthetics and artmaking. I don’t look at the work as an object or end product. I think deeply about everyday aesthetics. The form, subject, and process are not just things but ideas and emotions. And all of that is material. Everything is material. Because of that, two-dimensional work may take the lead at times and three-dimensional work may take the lead at others. How I see it, it’s kind of like a jazz band. Everyone gets to play, but at some points, someone gets a solo. Then, it returns to the rhythms.

ZB: When I first encountered your art, I was most struck by the conjuring of sound, even through visual cues. Where do your sonic inspirations come from, whether it be musicians or the sounds of everyday life?

ND: Music was probably my first recognized talent, as young as four. It started with me beating on books, pots, and pans with spoons. Even now, music has a deeper way of touching someone. There are a number of musicians I’m inspired by, but if I had to pick just one, it would be the drummer Chris Dave. The only reason I’m not a musician in the way I’m a visual artist and cultural practitioner is because I got kicked out of the band for arguing with the band director.

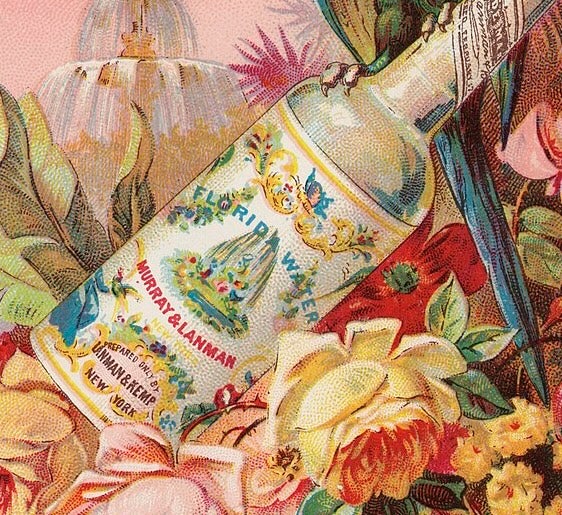

The sonic elements of my work come from everything—airplanes, cars, people mumbling, pens scribbling—they’re all sounds with the potential to be transformed into things other than what they are. One of my goals is to make works either using that sonic material directly or through visually representing sound patterns. The tambourine pieces started off as a way to force the viewer to think of what a tambourine’s jingle sounds like. When you see them, you’ll want to jingle them. Knowing you can’t make the sound with your hand, your brain imagines the sound instead. That’s how the art happens psychologically, not just visually.

ZB: On a related note, you recently played the drums in a performance at the Orange Show with Lisa E. Harris. Considering this and your background in music and sound, what role does performance play in your work?

ND: For every show I have I think of a performance to pair with it, although they don’t always come to fruition. More conceptually, I think of performance in the way I make my work. Making work with different types of strategies like collaging, sewing, arrangement, melting, and moving around is like dance. When I make one work, make another, deconstruct them both, and put them together, that is a type of performance in terms of process and materiality. Even gathering materials is a form of performance. It’s all about perspective and how we commit to particular definitions. I don’t want to limit performance to the body or the object. There’s enough space to move around in both.

With Lisa, that was the first time I played drums with a live band. That was a lifelong dream. I mean, I use drums to signify! With her performing regularly, as a soloist and with other musicians, it was really important to me. It took me back to when I was kicked out of the band in high school. How could this performance have materialized without that moment? Everything’s connected, it all circles back.

ZB: Your work is made of many found objects, some of which were gathered by donation calls to the Houston community. This aspect of your work and the narratives you convey feel very local. Not just in terms of the South or Texas, but mainly to Houston and Third Ward. What does it mean to engage locality in your work and your journeys outside of the South? How do people connect to your work despite being separated from these spaces?

ND: The studio is everything. It’s outside, it’s inside a building, it’s on top of the building, underneath the ground. It doesn’t have to be in a museum or gallery space.

Some things you can’t just separate yourself from. The way I see myself, my upbringing, and my knowledge outside of formal education have a lot to do with Third Ward. I think of South MacGregor as upward mobility, with the Cuney Homes as poverty. You can walk from one class system to the other in ten minutes. That duality of high and low is in the work, and I try to remove the distinctions. There’s an inside-versus-outside approach in that a lot of my materials aren’t necessarily traditional art materials. The resourcefulness of the imaginative working-class mindset is by using one thing to stand in for another that is not available. But then, there’s also a transformation of the materials in pushing back against class systems and spaces that are exclusionary. I view Blackness, particularly in Houston, through multiple lenses, not only as a social construct but also theoretically, metaphysically, etc.

Thinking specifically of Third Ward there’s a lot of contradiction, but it’s all culturally significant and rich— all things I find interesting. There’s a cat walking around with five hats on his head or [someone] playing sitcoms on a fifty-five-inch TV monitor in a wagon attached to a bike, riding through the neighborhood. That’s genius, see what I mean? All of that stuff. Because I’ve gathered these things from seeing them growing up, it would only be right for me to represent them. Again, I don’t solely land on it. It’s part of the thing, but it’s ‘this and that’ or ‘this, but that,’ so I try to create layers of meaning or questions through my practice.

ZB: What do you hope for or dream of for the future of your work?

ND: My hope is that I can still be healthy enough to make things. I wouldn’t mind having a band or a group and incorporating it into my work on a larger scale. I mean, Sanford Biggers has a group. Terry Atkins was in a group. Charles Gaines used to be in a group. Theaster Gates got a group. I could get a group too! (Laughs.) I definitely want to do more performances, either by myself, with another person, or have other participants perform the work. But I don’t know if I’m getting no Grammys anytime soon. (Laughs.)