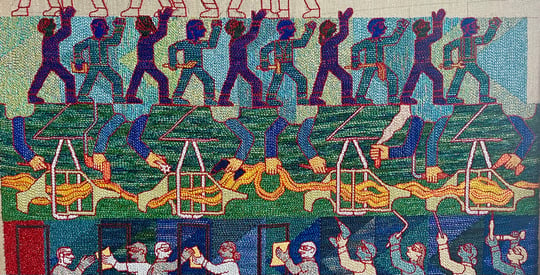

Anya M. Wallace is a visual artist and scholar born and raised in Florida. Currently, her studio, “The Laundry Building” is located in Bellefonte, PA. She is the Florence Levy Kay Postdoctoral Fellow in Black Feminist Studies at Brandeis University. Wallace currently defines herself as a multidisciplinary artist, “At the moment, my art practice is making in a constant state of displacement—mobile, transportable, and modular art making. I see with a photographer’s eye. Yet, I still love the paint brush. Right now, I’m working with watercolor and ink, mostly because of their modular nature. I also enjoy the use of collage as a medium to work with my own photography, painting, textiles, and calligraphy.” In the studio we discussed Wallace’s Naked Church Ladies series which includes water paintings of translucent faceless figures of Black church ladies in empowered sexual posture.

Logan Shanks: If the Naked Church Ladies was another medium, how would the piece change?

Anya M. Wallace: Well, I kind of have examples of that…because I tried. I wouldn’t call it critique, but the critique has been: “Go larger. Can you go large? Can you go larger?” And the hard part about doing that in watercolor is that the life that watercolor takes on is hard to just scale up. So, then I was like, “Well, I’ll just use acrylic and I’ll make them in acrylic,” but it’s not the same. It’s not the same movement and it’s not the same outcome and product. You’re not making watercolor Church ladies in acrylic on a large scale…it’s something else.

LS: So, you think the watercolor medium is where the church ladies are able to be the most free?

AW: I think so. It’s kind of like they come out of the page in watercolor, you know. I am helping guide them out.

LS: How do the Naked Church Ladies bring representation to different forms of Christian religious expression, particularly Afro-American religious expression in the South?

AW: When I was really, really young, my family attended a Black Catholic church (or Parish), St. George’s. I didn’t hear hollering in church. I didn’t hear clapping in church. We would occasionally clap along to an upbeat song or applaud after a special presentation or performance.

When I was about seven or nine, my family went to my stepdad’s family reunion in Vienna, GA, one summer. And for the very first time, I witnessed people clapping, shouting, and catching the Holy Ghost—these expressions that happen when you’re overwhelmed with the spirits and the flow of life…the energy of life…You know, speaking tongues and that kind of thing.

I think that the South is all over and through the Naked Church Ladies. Church hats in Black women’s aesthetic lexicon is a whole world unto itself. Yet, there is a relationship with aesthetics, beauty, and sensuality that is specific to the South, to the heat, to the tastes and flavors, sounds, and even violences of Southern living. These elements are conveyed through elements as the church ladies’ body types, flirtatious struts, rhythmic sways, and command of the church house. Their roles in the pulpit from choirmaster, to Usherette, Deaconess, Minister, and Freedom Fighter. These Women are leaders in the church as well as patrons. They clean it. They are its keepers. And they feed and tend to those who enter in need. To me, this is what the South is all about.

My memories from childhood are always with me. The women falling out and catching the Holy Ghost frightened me at first, and then I was intrigued by them and then those experiences in my childhood turned into this work.

LS: How do you think the Naked Church Ladies respond to culture of dissemblance[1][2] and respectability politics?

AW: I don’t want it to simply be a response. I would like to say it’s in a whole other metaverse, but it absolutely can be a response. When I took them to Italy [Black Portraiture[s] II: Imaging the Black Body and Re-staging Histories], I was surprised by the response from mature Black women, academics, and non-academics in the audience. What I remember is how much these women embraced the Church Ladies and expressed feeling seen.

There’s something very exquisite about the church ladies even though they’re naked, they’re not pornography. We can bring Audre Lorde’s The Uses of the Erotic[3] in here too, they evoke the erotic but they are not here to serve as pornography.

Having taken someone like my mentor Dr. Grace Hampton’s[4] advice on beefing up the hats on these stunning ladies prior to adding to the series, the intricacy thus became an indicator of not only Black Southern women’s sensual desires but also the extreme care and precision and craftsmanship that many Black women put into their presentation…clothed or unclothed. This can be for church. This can be for work. The school and city bus driver. The postal worker. The secretary. They are going to smell good. And they are going to look good. And that’s the point in making these pieces.

So, what surprised me about how they were received in their debut at Black Portraitures, by successful and mature Black women was that these women saw what I saw, they got what I was going for. They felt seen. And they liked what was being reflected back to them. Somehow, that initial reception quelled any anxieties I might have been carrying around this work and respectability politics. There didn’t seem to be room for respectability standards in the space. That in a way confirmed for me that they were exactly what they needed to be, medium size, politics, and all.

Because you know Black women—our grandmothers like when you go out there and make them proud, you know, you make them look good. And I did it in a creative, innovative way. It’s kind of sexy and thrilling too.

LS: I’m thinking about these two extremes of danger and then pleasure and then the work being in the middle, balancing those contradictions. That’s kind of how I see it.

AW: Yes, there is that and there’s also discipline, but you know it is an important thing in my work. There’s the discipline of dressing and preparing the body for church, so the hat is an indicator of that in the paintings, it’s evoking the spirit of the church house. [It’s a reminder of] what you do on Sunday mornings to prepare to get there. That’s a process—preparing for church and looking good you know and there’s a discipline in that. So, we’re also playing with profane and sacred here…like the nakedness and then the church hats are juxtaposed to bring out all of those polarities…profane and sacred…free and disciplined…free and constrained…pleasure and pain.

LS: It is reconciling with all those things at the same time, so it makes the piece balanced. I was going to ask if each individual church lady has a personality and a story, but I feel like that’s not necessarily where your work lands.

AW: It’s more about the movement that comes out of her. Then, she becomes a church lady— the movement or the action that she’s doing happens on the page first and then the portrait is indicated through the hat being placed, because that’s going to indicate where the head is. In a lot of them, they don’t actually have a head, like a visible head [with] eyes, so they have personalities through their actions or their roles in the church or service. It is not so much about the traditional linear story but more so [about] the action that comes out on the paper.

The sexual violence of Black women haunts the soil of the American South. Black women mediate this tragic history through Black feminist theory and art. It is difficult to imagine a world where Black women can evade pain, injury, and violence and transcend into a portal where their beauty and care ethics serve as erotic freedom-making rituals. This series honors the legacy of Black women working in constrained labor conditions, yet still striving to express creative subjectivity. Through meditating a site of Black respectability politics—the Black Church, Wallace’s Naked Church Ladies series celebrates Black femme creative sexual expression, adornment, pleasure, and play by displaying Black femme flesh and sexuality in its most free form.

[1] Culture of Dissemblance is a concept that first appears in Dr. Darlene Clark Hine’s “Rape and the Inner Lives of Black Women in the Middle West”. Culture of Dissemblance describes the cultural behavior of Black women to conceal their inner selves as a means to protect themselves from various forms of violence.

[2] Hine, D. C. (1989). Rape and the Inner Lives of Black Women in the Middle West. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 14(4), 912–920. https://doi.org/10.1086/494552

[3] Lorde, Audre. The Uses of the Erotic. Brooklyn, N.Y: Out & Out Books, 1978.

[4] Grace Hampton is a Professor Emerita of Art, Art Education, Integrative Arts, and African Arts at The Pennsylvania State University. She is a mentor of Dr. Anya Wallace.