It starts with an orb, at least according to Jacob Todd Broussard. The artist points towards a small work by the lesser-known modernist painter Forrest Bess, Untitled (1950),”1 by addressing it in his painting and the accompanying essay by Emile Mausner also speaks to the work. Bess’ painting is a strange object, employing scarce symbols sourced from a dream state and framed in driftwood sourced near his home. In Broussard’s painting it is framed once, then twice more, viewed on an older television as an Antiques Roadshow segment. This translation, from dream-like vision to painting to television broadcast to painting again, is essential to understanding Broussard’s secret histories. I likely would’ve never seen Bess’ painting without Broussard as my guide.

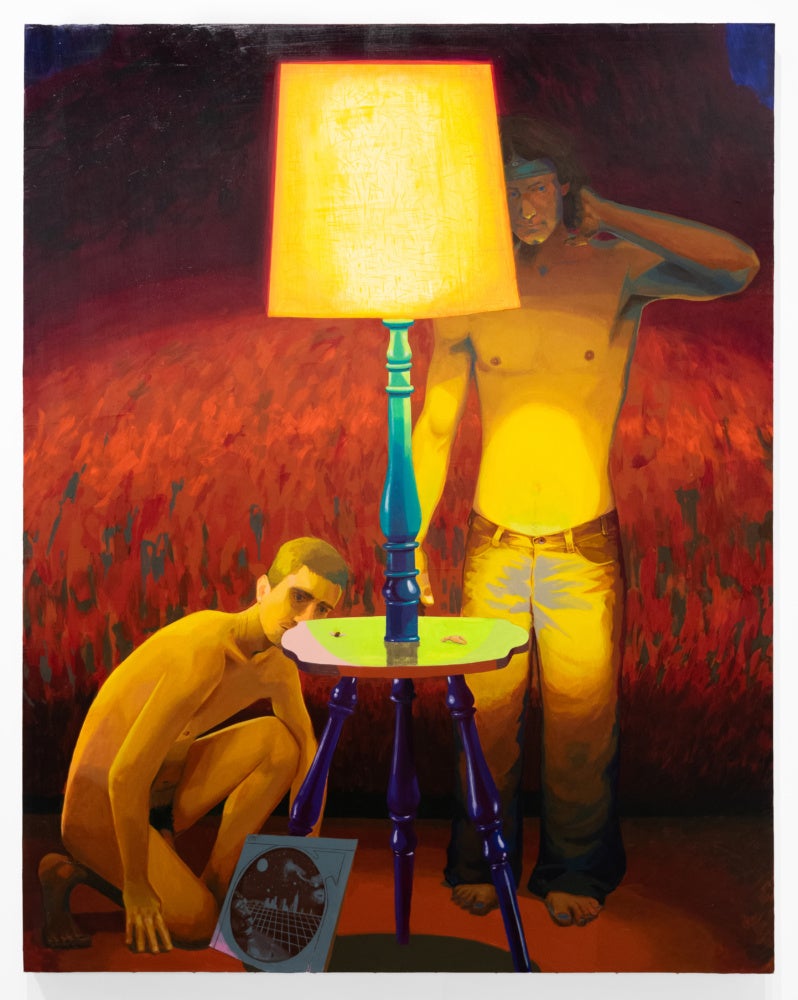

Deathbed Scene at Atlanta’s Wolfgang Gallery is representative of Broussard’s hyper-referential practice, extending the work beyond its painterly origins and into sculptural space and time. Images are presented as sculptural ephemera, taped to makeshift lampshades, while also appearing again as lifelike recreations or trompe-l’œil in paintings. The lamps are a new addition to Broussard’s language, showing images without the distance of being painted or otherwise rendered. He refers to them as “Attempted Light Cones,” referencing a theory of relativity comparing the passage of time to the properties of light. Maybe this is a painting show about photographs. Many of the images in the exhibition are without this historical provenance, existing as general old stuff, a formless archive for the artist to draw from. The anachronistic objects suggest a precarity, though closer inspection reveals a preciousness in the use of white, acid-free artist’s tape. Their disorderly accumulation of images and objects implies an abundance of information, an assumed queer underground from which Broussard often pulls from.

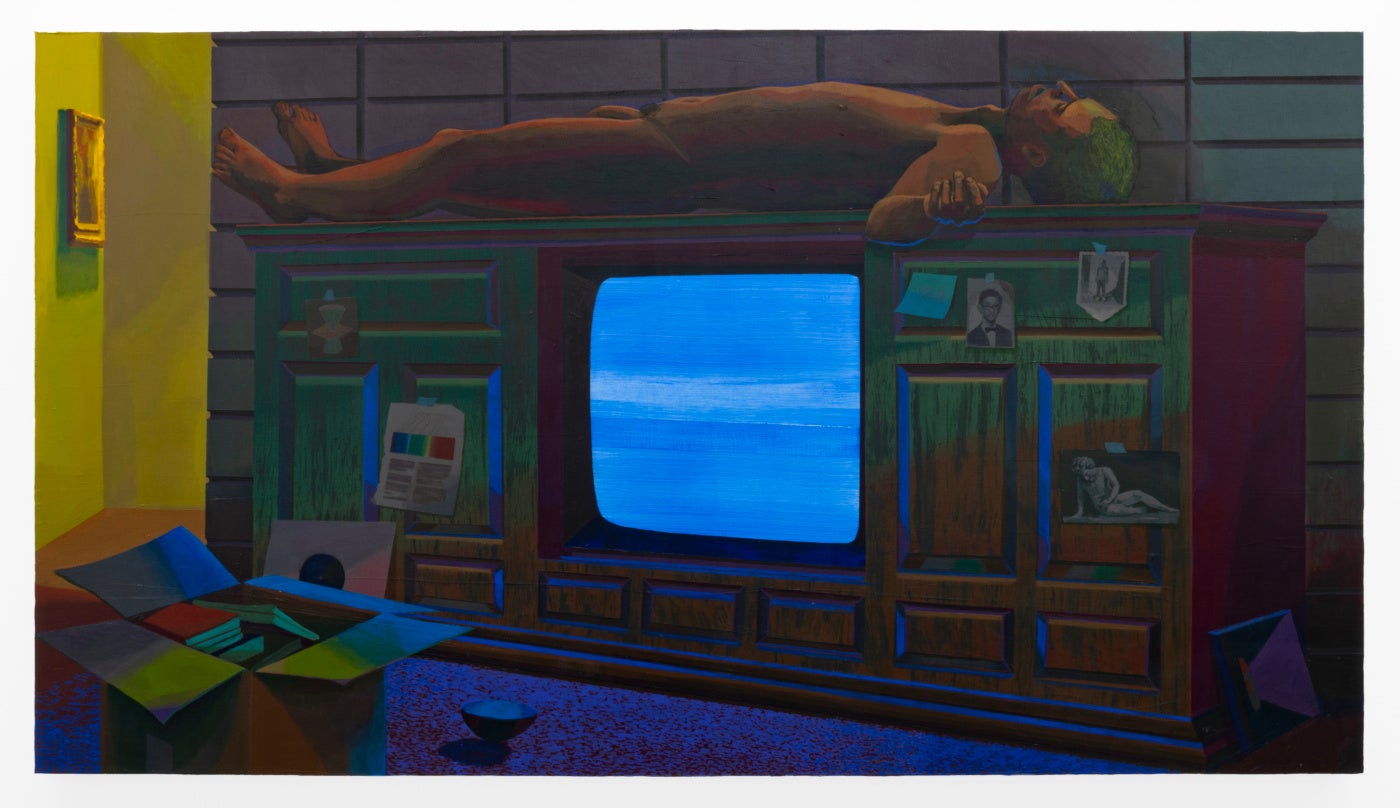

The primary subject is revealed in the title: Deathbed Scene. A young man rests horizontally atop a dated television console, perhaps acting as a coffin or hospital bed. The deathbed scene is a particular trope in television and cinema; I imagine dramatic lighting and delivery of a character’s last words. By repeatedly painting this scene, Broussard makes something as abstract and diluted as death apparent, visible. The lack of life is the subject. Death has been addressed in other ways, for example, the memento-mori, and while there are several deaths (a dead fly, a crab leg), the exhibition is too broad to be understood as a singular gesture. An obvious read may be that of a eulogy to the AIDS generation, an acknowledgement of a lost generation. Yet, as Covid-19 has made visible, the human body is fragile and weird, morality is not some faraway island but instead integrated into our quotidian activities.

One detail among many, an LP by Patrick Crowley, leans against a table in The Appraisers (2023), providing a helpful anecdote to Broussard’s practice. Crowley was a prolific electronic music producer in the 1970’s who died from the AIDS virus in 1982. Crowley is currently the subject of multiple reissue projects by Dark Entries Records, his work circulating as full length projects pressed on vinyl records, tapes, and of course, streaming services. His musical afterlife exists among those in the know, rather than the disco heights he reached in his lifetime. It is a strange afterlife, a similar fate to that of Arthur Russell or SOPHIE, when an artist so interested in the populist mission of Pop music becomes an obscure footnote for the diehards.

Back to the orb. Broussard has referenced the light cone in the titles of individual works, a theory that the present is situated between two “cones” meeting at their points, the past and the future, informed by larger properties of how light travels from a singular event. It is an ambitious proposition, and there is something earnest about Broussard attempting to make his own models with makeshift household materials. Perhaps at this converging of two points is Bess’ orb, where the vastness of history and the future meet, a gateway between the two. Does time exist without death? This is an impossible task for beings who measure time with ephemeral bodies.

Writing as a gay man who experienced the AIDS epidemic second-hand, via a passive absence rather than an active losing, how does one move forward while honoring those who have passed? The photograph may be the best that we have, or other bits of ephemera as defined by Jose Esteban Muñoz in Cruising Utopia2. Yet these bits and pieces are understood to be indexes of something larger, a signal from the past towards an implied future. Illustrated Greek vases sit alongside softcore erotica and in jokes from vintage gay magazines, postcards with illustrated bits from art history. There is, of course, a drawing of a blowjob, so the mind never wanders too far. The question remains, can you be gay without the archive?

[1] The work is assumed to be untitled, although “Number 30,” is inscribed on the verso, likely by Bess’ gallery, Betty Parsons.

[2] “[…] queer evidence: an evidence that has been queered in relation to the laws of what counts as proof,” José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York, New York: New York University Press, 2009) p. 65.