The basic challenge of life is dealing with the fact that we have—or are—bodies. Art meets this challenge in two ways. One is through representation, in which bodies can be freely idealized, abstracted, or fractured. Another is by eliciting bodily changes, such as laughs, winces, gasps, and other responses that go with our emotions. Artworks show us bodies and act through them.

The two quite different exhibitions currently on view at the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art in Charleston are linked by their use of both of these strategies. Jody Zellen’s complex practice, which includes digital photo manipulation, painting, and making mobile apps, could be classified with New Media Art and the related practices of net.art. However, unlike some joyless exercises that fall under those theoretical rubrics, hers is a refreshing escape that is both playful and conceptually sophisticated.

The title of her exhibition, “Above the Fold,” is a now-quaint reference to the newspaper layout practice of placing the most significant headlines and images at the top of the front page, where they are guaranteed to attract viewers. Even though newspapers are now websites, the concept still applies: rather than a physical document, there is the space at the top of the browser window, which remains the first thing seen when the site loads. The principal difference is that, unlike in the frozen medium of print, top of the page placement is contingent and changeable, with images and stories being rotated through as the infinite news cycle rolls on.

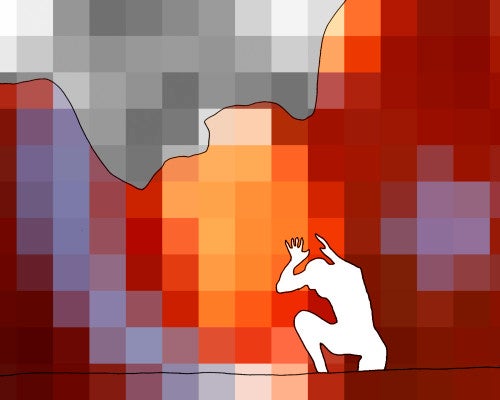

This protean recombination provided the basis for one of Zellen’s net.art works, All The News Thats Fit To Print (2006). In the current exhibition, her digital collages take such strategically placed news images as their source material, processing them until they become grids of pure colored squares. Objects and figures dissolve, leaving only a coarse overall distribution of hues across the scene. This is a reduction of information, in the strict technical sense: it increases the uncertainty of the message. Does that bloom of red, orange, and yellow indicate an explosion? Is that expanse of purple part of the sky or a building? It’s impossible to recover the original source with any specificity. This is not the chance operation of noise, but a calibrated visual expression of the ambiguity built into the very design of news messages.

Zellen uses these grids as a backdrop or field for both her digital collages and gouaches on paper. Human figures reduced to outline shapes wander in a flattened and perspective-free space shared with loose bits of hand-drawn text. It’s tempting to string these decontextualized words back into sentences—the juxtaposition of “THINKING/ BEGINS/ BEYOND/ DECODING” was irresistible—but again, too little of the original message remains. The actions of the figures, too, become unidentifiable when removed from any sensible social or physical surroundings, though their minimally sketched expressions and posture occasionally hint at frustration, sorrow, or joy.

The gouache works have a looser feeling than the digital images. The squares don’t quite perfectly line up with each other, and the hand-painted hues are imperfectly distributed inside them. The Austrian artist Peter Weibel has proposed that the post-media condition involves a phase in which all media interpenetrate, refer to, and mimic one another. While this is often a useful organizing concept for digitally derived art, Zellen’s works do not seem to be post-media in this sense. Unlike other artists such as Austin Lee or Laura Owens, Zellen isn’t trying to re-create the look of the digital in paint. These are not just transpositions of images from one medium to another, but rather medium-sensitive ways of working out related ideas.

In “The Photographic Message,” Barthes appealed to information theory (or its jargon, at any rate) to explain the semiotic functions of press photography. Zellen’s works take these messages apart rigorously, leaving only fragmentary elements to anchor our interpretations of what we see. Overall scene or context is separated from figures, who in turn are separated from their own actions and expressions, and both of these are separated from headlines and captions. These elements, though they occupy the same frame, cannot seem to connect with one another. The source images are abstractions, with text drifting like clouds past people who have been hollowed out and cut loose.

Such heavy-duty semiotic machinery could easily be wielded pedantically, but Zellen’s work neatly avoids this trap. Everything has a charmingly wobbly, hand-drawn quality, even in the digital works, and the minimally outlined people leap exuberantly as often as they seem downtrodden. There are clear stylistic affinities here with Saul Steinberg’s cartoons, as well as with contemporary street art, particularly Keith Haring and Invader, the French artist whose signature images are blocky pixel figures from classic video games.

These influences are also prominent in the black-and-white “doodle drawings” with their dense whirls of anonymous figures and buildings. Zellen’s fusion of critique and play is at its absolute best in Time Jitters (2014), an installation room created for this exhibition in collaboration with faculty from the College of Charleston. Two of the interior walls cycle through a series of stills and color patches, mimicking the restless refreshing of headlines. The other two appear blank until you enter the room, when several overhead object tracking cameras lock onto your location and display an image on both walls at once. The tracking system then enables your body to serve as an interface. As you move through the room, the images on the facing walls follow you, giving rise to an uncanny dynamic of being both pursuer and pursued, as if it were possible to be hunted by an image. The images themselves change throughout this pursuit. At the furthest distance away, they are tiny black-and-white outlines, but as you approach they become ordinary photographs, then blocky abstract grids, and finally grids with superimposed figures.

There is an implicit epistemology at work in these transitions: acting on the desire to see more only causes the picture to dissolve further. It’s hard not to be drawn in by the physical act of ping-ponging back and forth in the space, chasing pictures like butterflies. Despite the habitual tendency to view digitally derived art as invested in the dematerialization of images, Zellen’s work ultimately engages in a systematic re-materialization: from files and code back into paper and pigment, and ultimately back to the body, the seat of our pleasures and sentiments.

In Business as Usual, Bob Trotman’s works present a sharper edge than Zellen’s, one that is darker and more satirical. Based in North Carolina, Trotman is a sculptor working in wood, here primarily basswood and poplar. His pieces are figurative, consisting of dramatized tableaux of the office and the psychological horrors of corporate life.

Trotman’s protagonists tend to be marked as either bosses or subordinates. The latter are easily recognized by their poses of desperation: either sinking, falling, or utterly collapsed. In the case of Desk Man (2011), the victim lies on his side, his arms raised up towards his head as if to deflect invisible blows. The massive desk he rests on resembles an altar or an autopsy table, an impression strengthened by the two floor lamps flanking it.

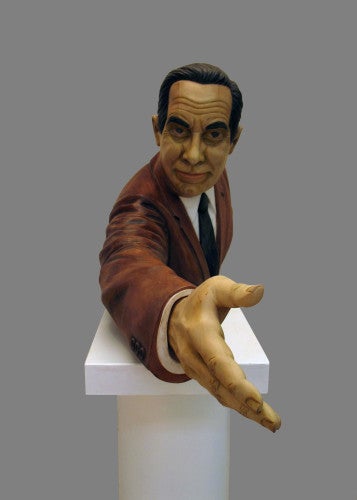

Other pieces radiate triumph and menace. The most potent of these is Shaker, made up of nothing more than the head, upper torso, and outstretched right arm of a characteristically suited man. He leans in just a touch too far, his fingers slightly hooked but not yet claws; his face is Satanically compelling, dominated by thick dark brows over too-large eyes. Fixed on a pedestal, he rotates slowly in place, casting his impassive panoptic gaze towards all corners.

Trotman has associated these characters with nautical figureheads, a resonant connection given that the wood they are carved from appears to be the very furniture and paneling of the boardroom. Many figures are truncated, disassembled, or reduced to symbols. The box man of No Way is nothing more than a head and shoulders and a pair of feet affixed to a walking spray-painted negation.

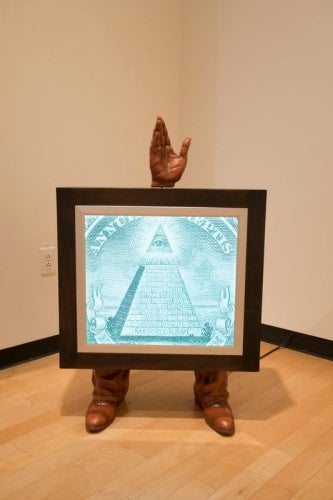

In Ascendency of Desire, a meaty hand wearing a “VIP” ring juts skyward from a lightbox mounted with a detail from a dollar bill. Five disembodied heads with their ratlike features make up the Quorum, which occasionally lights up in a blaze of orange light. These exaggerated, caricaturish faces resemble some of R. Crumb’s creations—consider Whiteman and other repressed, depraved businessmen.

Trotman, like Crumb at times, also has a blend of contempt and sympathy for his subjects. In an interview that accompanies the exhibition, he pointedly observes that “everybody thinks that they [the sculptures] are somebody else.” The implication is that viewers are often unwilling to recognize their own complicity with the bosses, or the craven passivity they share with the workers. Undoubtedly there is something to this, but the simple binary hierarchy Trotman imposes (boss or worker?) leaves little room for nuance or the kind of projective, humanizing identification he wants to encourage. In one way, the works in Business as Usual could not be more timely.

The movements gathered under the banner of Occupy Wall Street have rekindled popular interest in the critical discourse of class and economic inequality. Seen in this light, Trotman’s works might aim to be a lance in the side of the one percent. But in another way, they feel strangely displaced in time. The totalizing world of the office, with its rigid dress code and social hierarchies, its dark wood and potted plants, seems like more of a relic than a reflection of the contemporary reality of corporate work.

Today’s contingent, disposable workers can only fantasize about this kind of bygone world, where discarding one’s individuality in order to conform could at least bring the benefits of prosperity and security. Trotman’s barbs draw blood, but from targets that may, at this point, have vanished into popular fantasy and the past.

“Above the Fold” and “Business as Usual” are on view at the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art at the College of Charleston through March 8. Dan Weiskopf is an associate professor of philosophy and an associate faculty member in the Neuroscience Institute at Georgia State University. He is the author, with Fred Adams, of An Introduction to the Philosophy of Psychology, forthcoming from Cambridge University Press.