Earlier this year, Savannah-based independent publisher Aint-Bad released an open call for “photographs and essays from those who live and make work in and about the south. Particularly, how is it being defined, re-defined, undefined and co-defined within the contemporary conceptions of the American South?” The works selected from submissions were to be included in an upcoming issue of Aint-Bad dedicated to the American South, the second time the publication had focused on the topic since its founding by five photographers and writers associated with the graduate photography program at the Savannah College of Art and Design. Since 2011, Aint-Bad has published fourteen magazines and thirty-two monographs, primarily featuring the work of young, emerging photographers and recent graduates from prestigious photography MFA programs. The platform has amassed a significant following and has collaborated with festivals and institutions such as Atlanta Celebrates Photography, FotoFest, and the SCAD Museum of Art.

On Thursday, May 7, applicants to No. 15: The American South received an email from Aint-Bad thanking them for their submissions—which had required a fee of forty-five dollars to be considered—and listing the eighteen photographers who had been selected for the upcoming issue: Amanda Greene, Ashley Kaye, Cassandra Klos, Due South Co-op, Evan Perkins, Gabriel McCurdy, Jared Ragland, Jill Frank, Julianne Clark, Matt Eich, Matthew Jessie, Phillip Abbott, Robert Gordon, Rosie Brock, Shane Rocheleau, Susan Worsham, Virginia Hanusik, and Whitten Sabbatini. One of the applicants whose submission was declined shared the email with Brooklyn-based photographer Miranda Barnes on Friday, May 8. According to Barnes, the photographer expressed a suspicion that all eighteen of the selected photographers were white, which Barnes then verified through research. Likwise in No. 8, the first Aint-Bad publication dedicated to the American South, Tommy Kha appears to have been the only non-white photographer featured.

Later that day, Barnes posted a screenshot of the email from Aint-Bad overlaid with text in her Instagram Stories. Her text read, in part, “What does it mean when an open call is held for the ‘American South’ and the print finalists are all white? How many submitted photographs featured a black person and yet [were] not photographed by a black person?… [What] does that tell black photographers who look at this or who were denied?”

This post by Barnes on May 8 was in turn reposted by several Black photographers, one of whom shared the story with Burnaway. This critical response to the selection of all-white photographers eventually led Aint-Bad to release a series of updates on the upcoming issue over the past weekend. The original statement begins, “Aint-Bad recognizes that even sincere decisions made with the purest intentions sometimes fall short and require reconsideration. In that spirit, we are expanding the selections for the upcoming American South edition and will announce (in the days ahead) additional photographers to be included.” A revised statement released on Sunday, May 10, rescinds this expanded open call, instead claiming that “[before] any further call for entry, Aint-Bad will assemble a committee (of diverse individuals from the community) to directly address the issue of societal representation in curation.”

When Barnes spoke with Burnaway on Tuesday, May 12, she described long-running conversations about the erasure of Black photographers’ work and the pernicious effects of white supremacy within curatorial decisions were already taking place within Black photography communities. She also acknowledged—as she had in her Instagram Story on the previous Friday—that the long-delayed arrests of the father and son now charged with felony murder of Ahmad Arbery in Brunswick, Georgia, had heightened many Black artists’ sensitivity to the racist treatment Black people face in the United States. Barnes further noted that her response was also partially motivated by reports that Black Americans are dying from COVID-19 at drastically higher rates than their non-Black counterparts, particularly in the South. She said that she felt it was no coincidence that her negative response had garnered attention, noting that the work of calling attention to such structural abuses often falls upon Black women in particular.

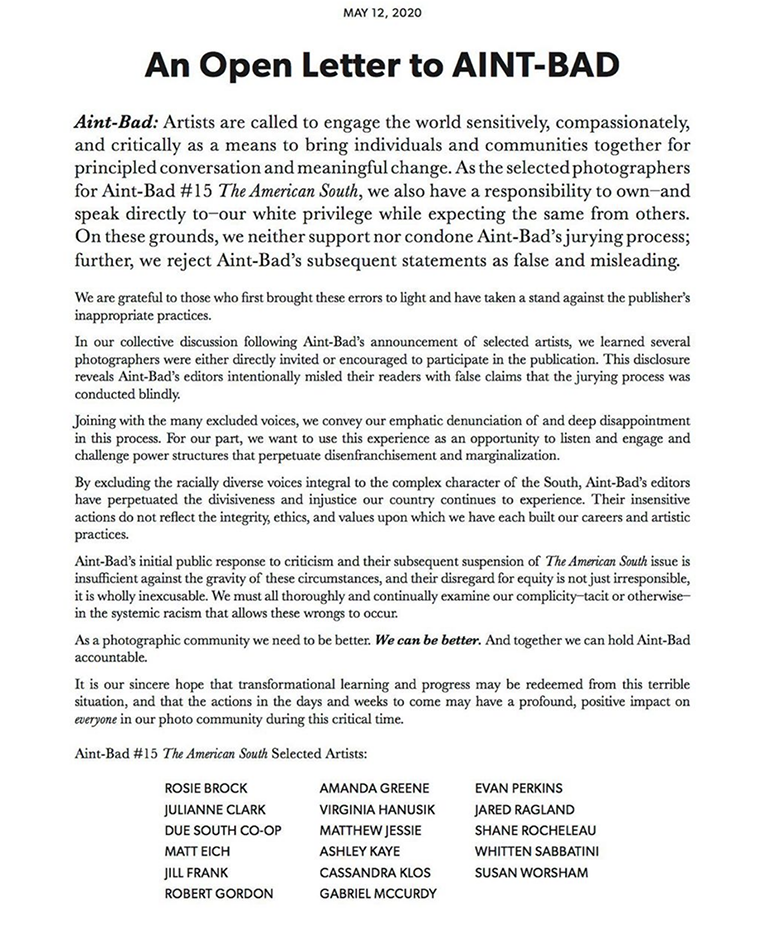

On the evening of May 12, seventeen of the eighteen selected artists released an open letter to Aint-Bad over Instagram. It reads, in part,

As the selected photographers for Aint-Bad #15 The American South, we also have a responsibility to own—and speak directly to—our white privilege while expecting the same from others. On these grounds we neither support nor condone Aint-Bad’s jurying process; further we reject Aint-Bad’s subsequent statements as false and misleading…

ADVERTISEMENTIn our collective discussion following Aint-Bad’s announcement of selected artists, we learned several photographers were either directly invited or encouraged to participate in the publication. This disclosure reveals that Aint-Bad’s editors intentionally misled their readers with false claims that the jurying process was conducted blindly…

By excluding the racially diverse voices integral to the complex character of the South, Aint-Bad’s editors have perpetuated the divisiveness and injustice our country continues to experience. Their insensitive actions do not reflect the integrity, ethics, and values upon which we have each built our careers and artistic practices.

As of 5 pm today, Aint-Bad has not responded to Burnaway’s multiple requests for comment on this story.