We continue our coverage of the Southern Prize finalists and winners with this studio visit with Masud Olufani, conducted well before the prize was announced. Click here to learn about the prize and see the work of top winner, Noelle Mason.

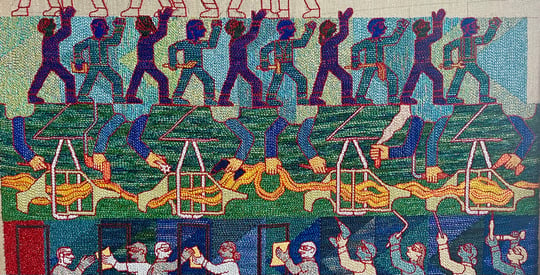

In 2016, Masud Olufani declared his arrival as a visual arts tour de force in Atlanta with his solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia (MOCA GA) titled “Poetics of the Disembodied.” It was his provocative video Blocked that held my prolonged attention. It featured the projection of an image created by the Atlanta History Center. On the left side is a well-known image by George N. Barnard of the Thomas Frazer and Company slave auction house at 8 Whitehall Street taken in 1864 during the Civil War. On the right side is a current view of the Five Points MARTA Station. Olufani then superimposed this image of the Frazer Auction House on images of other parts of the Five Points Station in a rotating sequence.

In late January of this year, I visited with Olufani in his studio to see what he’s working on. As luck would have it, Paul Stephen Benjamin was there when I arrived. Here is the discussion that ensued.

Carl Rojas: What drives your art practice?

Masud Olufani: My work is rooted in a kind of spiritual/historical place that I don’t really get into that directly. I’m not an artist who comments on contemporary political events. I guess the most political thing that I did recently was a piece in my last show [at MOCA GA] about mass incarceration. It’s a contemporary subject, but it has been going on since the end of slavery.

CR: African-Americans went from slavery to second-class citizens. I felt like we were beginning to make progress with Obama and the notions and possibilities of a post-racial America, and now here we are taking two steps back with the election of POTUS 45.

MO: I view these situations like a speed bump. The world is becoming smaller and more global. It is inevitable. We’re going to get to a point where there really is a sense of oneness among people, but it’s going to take time. In a piece of art, if I deconstruct it and take it from macro to micro, I have forward progress and then a step back. I come in one day and things are moving very well, and then I come in the next day and I’m like “dang … this sucks. Why do I keep doing this?” But you know, I keep coming in, because I know that if I keep doing this, it’s going to get better.

CR: I like the direction of your new work. What are these drawings?

MO: These are based on my Katrina Suite (2017) drawings. The African diaspora experience is conveyed in these iterations of water. So, water as destroyer, water as place of redemption, water as point of feeling, water as port of transport.

This pod piece on the floor is part of Snip/Hive (2017). I’ve put a sound device inside. It’s going to be covered in a translucent material so that you can see the interior structure, and on the surface I’ll make detailed drawings of slave families from the 1800s. When you get close to the piece, you will trip a recording of bees buzzing. That will play for about 20 seconds and then you’ll hear the Fisk University Jubilee singing the Negro Spiritual “Oh Freedom.” So the whole idea for the piece has been snipped from this branch.

CR: Tell me more about the dome piece.

MO: This dome form is part of a piece called the Unmoored (2017). The design comes from a dome form prevalent in Portugal and Brazil. I’ve made it into a trapping device to comment on the power of the religious church state and the way it traps cultures.

CR: That has a lot of meaning for me because I was reared Roman Catholic, so I appreciate the trapping element.

MO: I met this sister from South America. She was Catholic and we were talking about her religious experience. She flipped out because she is from the indigenous, native community of her country. She said, “we can’t stand them, the Catholic church, because when they came in, they decimated our community.” She had a visceral reaction to that narrative in her country. A lot of interesting connotations come out of it. There is the African interaction, but also the indigenous Brazilian …

CR: At what age did you become cognizant of slavery as a historical event?

MO: I used to live in Rockaway, Queens, and I was going to the arts high school in Newark, New Jersey, because I couldn’t get into LaGuardia [High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts] in New York because we didn’t live in the district. So I would get up at five every morning, take the bus to the train station in Queens, then take the train to Manhattan, then take another train in Manhattan down to the World Trade Center station, catch the train to New Jersey, then take the bus up the hill to get to school. So I had all of that time to read. It was during that time that I started reading Nikki Giovanni, Sonia Sanchez, Toni Morrison, Baldwin, etc., and developed an interest in history. Obviously seeing Roots as a kid … my parents sat me down every night it came on …

CR: I think Roots brought it home for all of us.

MO: They did a good job on the new one too.

CR: When was it for you, Paul, being cognizant of the history of slavery and black culture, the African diaspora …

Paul Stephen Benjamin: It was a little different for me, growing up on the South Side of Chicago. Chicago is very segregated. In my insulated community, I didn’t deal with it. It wasn’t a conversation we had to have in the house. Roots being the first and only.

MO: We weren’t taught about slavery in school. I think slavery was discussed, but as a footnote: “This happened, it was bad, let’s move on to Thomas Jefferson.”

CR: What was your work like when you were at SCAD-Atlanta?

MO: I went to grad school twice. I also went to Virginia Commonwealth University. Man, I hated Richmond. This was when they were trying to decide whether or not to put [tennis champion] Arthur Ashe’s statue up on Monument Avenue with all of the Civil War generals. They couldn’t agree if he belonged there because he wasn’t a war hero … The argument was, well, neither were these guys. For that and other reasons, I left Richmond. I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I started making art again and had a studio out in Marietta for a while. I was under the radar and no one knew what I was doing. I wound up at SCAD eventually. My work has always been real strong in material relationships—materials infused with their own kind of historiography that I like to point to but not really manipulate too much. I try to have a light touch with materials. Certain materials I think are already impregnated with this really rich history and all you have to do is show them and people start making these associations.

CR: Like chains?

MO: Yeah, like what else do you need to say? For me, grad school was about having a place to work, and I get a degree out of it. I had a clear direction of where I was going already, but I think my work has grown alot since graduating and doing some residencies. In grad school, I was trying to figure out these connections, the allegories, and how these materials speak to each other. Then things started to click.

CR: Let’s talk about Blocked (2016). It really caught my attention at your MOCA GA exhibition.

MO: I’m proposing a project called Blocked at Five Points, because Five Points used to be the site of a slave auction. It grew from a documentary project I did with Georgia Public Broadcasting called 37 Weeks Sherman on the March. I was the narrator. In the film, they show photos of Atlanta during the 1800s and then morph them into photos of the sites today. One showed this slave market at what is now the Five Points MARTA station. Overwhelmingly, black folks come to that MARTA station every day and very few people know what took place there. I think Atlanta is turning its back on a whole revenue stream because there is such a rich history here. If Atlanta were to embrace its troubled history, I think people would come here for research and for tours. It’s a whole revenue stream they could leverage if they would just embrace its history, like Savannah. But Savannah doesn’t have a choice because all of its buildings were left intact by Sherman, so the architecture speaks to the history. I don’t know what Atlanta is afraid of. Just embrace it. It happened.

The other irony of Blocked is that the Margaret Mitchell House is a mile up the road and one of the central figures in her narrative is a Mammy. So you have fictional slavery commemorated in a place a mile up the road, and you have real slavery that took place at Five Points that doesn’t even have a historical marker.

CR: Your proposal made me aware of something that I didn’t know about. It helps me understand who we are as a city. It doesn’t surprise me that that was where the slave auction was because that’s where all the railroads came together. When I saw that piece in your show at MOCA, I was dumbfounded. It really hit me hard. That’s when I started to ask other people if they knew that the slave auction houses were at Five Points, and most people didn’t. Whether we like it or not, I think it would be good for the community to see some evidence of it.

MO: Yeah, we have to wrestle with that history. It’s like a troubled family with a big secret. We all know what happened, so let’s just talk about it. Let’s stop pretending that it’s not there.

CR: There are a lot of places on the Westside that deserve historical recognition: Hunter Avenue Baptist Church, Paschal’s, and the influence of the HBCU schools in the movement. Why don’t we highlight any of that? What happened there help change the country, the world! Instead, we get Trump picking on John Lewis.

MO: But you know what? He picked on John McCain for being captured. I was like, dude, are you serious? The closest you have been to war is probably the Fourth of July. But you say that to someone who went to Vietnam and spent time in a POW camp … wow. This guy isn’t playing with a full deck. I was always taught when I was growing up, don’t argue with a fool—and he’s a fool.

PSB: Did you all get down to Columbus to see the dialogue between Kara Walker and her dad Larry?

CR:Kirsten Pai Buick, one of the Driskell Prize winners, isn’t a Kara Walker fan. She thinks that she is exploiting the same black experience that white people use to trap black people with. I found that very provocative. It made me look at her work differently.

MO: There was a lot of backlash to Kara’s work. Alison Saar came out against her. There was a whole group of contemporary black artists who had a problem with her work. It’s interesting because her work for me, it’s uncomfortable, but I think that is what she is trying to go after, intentionally.

If we are just looking at it from the terms of aesthetics, I think it is beautiful work, but I look at this stuff sometimes and I feel uncomfortable. I’m like, shit, really? That being said, she has the right to make whatever the hell she wants to make. I find one of the most interesting things about her is how different she is from her father.

CR: I know you’re also an actor. How does acting influence your art? Or does it?

MO: I think the recent inclusion of performance in the work comes out of that. Working with T. Lang dance on Katrina Suite (2017) is a nod to performance.

CR: I enjoyed the singer at your talk [at MOCA GA]. That was a nice surprise.

MO: I loved the way she walked into the space, mounted the block, and just started singing. I actually used her again for the project I did for SCAD, the film.

CR: What was that?

MO: The Visionaries Project. So, Jen Library in SCAD Savannah was the site of the first sit-in movement in Savannah, so SCAD wanted to commemorate that and they asked me to put together a film as part of it. So I did a performance piece/art piece. We picked the three people who were arrested during the sit-in in the library, which used to be Levy’s department store when that took place. So I had those three portraits lined up., and then the singer mounted a block and began singing. Then I entered from off camera, I look at the portraits, and then look at the camera and recite the Declaration of Independence. SCAD had a 50-foot screen, so you had a giant image of me reciting the Declaration of Independence—it was freaking crazy.

CR: Does anyone ever ask you if you’re angry?

MO: No. I don’t think anyone’s ever asked me if I’m angry. I don’t feel angry.

CR: I’m thinking of the machete. The trap. I’m thinking of possible connections to lynchings. I guess it just paints a picture of the violence of the past?

MO: I think so. Maybe there’s something there about the severing of connections that I find interesting. Maybe that goes back to experiencing the divorce of my parents. Some violence going on in the household. That might have something to do with it. But yeah, there’s something about the severing of family ties, connections, genealogy. The maintaining of that under severe stress conditions and also the severing of it. There’s something about that I seemed to be drawn to. How much of that is in my subconscious and how much of that I am aware of – I’m not sure. But yes, the violence of the past, I seem to just be drawn to.

Carl Rojas is an art enthusiast because he is married to BURNAWAY’s Executive Editor.