New Orleans is a city that bears the brunt of the country’s excesses. The oil industry’s indefatigable drilling has eaten away at the coastline’s natural barriers, which are increasingly battered by storms fed on the steroids of CO2–a byproduct of the quintessential American lifestyle. Other fuels of American excess, like sugar and alcohol, are ingested and expelled in nauseating abundance by visitors to the French Quarter, itself a microcosm of the venal foundations of U.S. history most likely to be repressed: genocide and slavery. Despite current revisionist attempts, the inequity at the base of that history will keep rising up like oil hemorrhaging from a shoddy BP well until it’s dealt with. Cuban American artist Luis Cruz Azaceta sees these upsurges of our inhumane history with the clarity of a prophet in exile, as evident from his retrospective, What a Wonderful World, on view at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art through July 24, 2022.

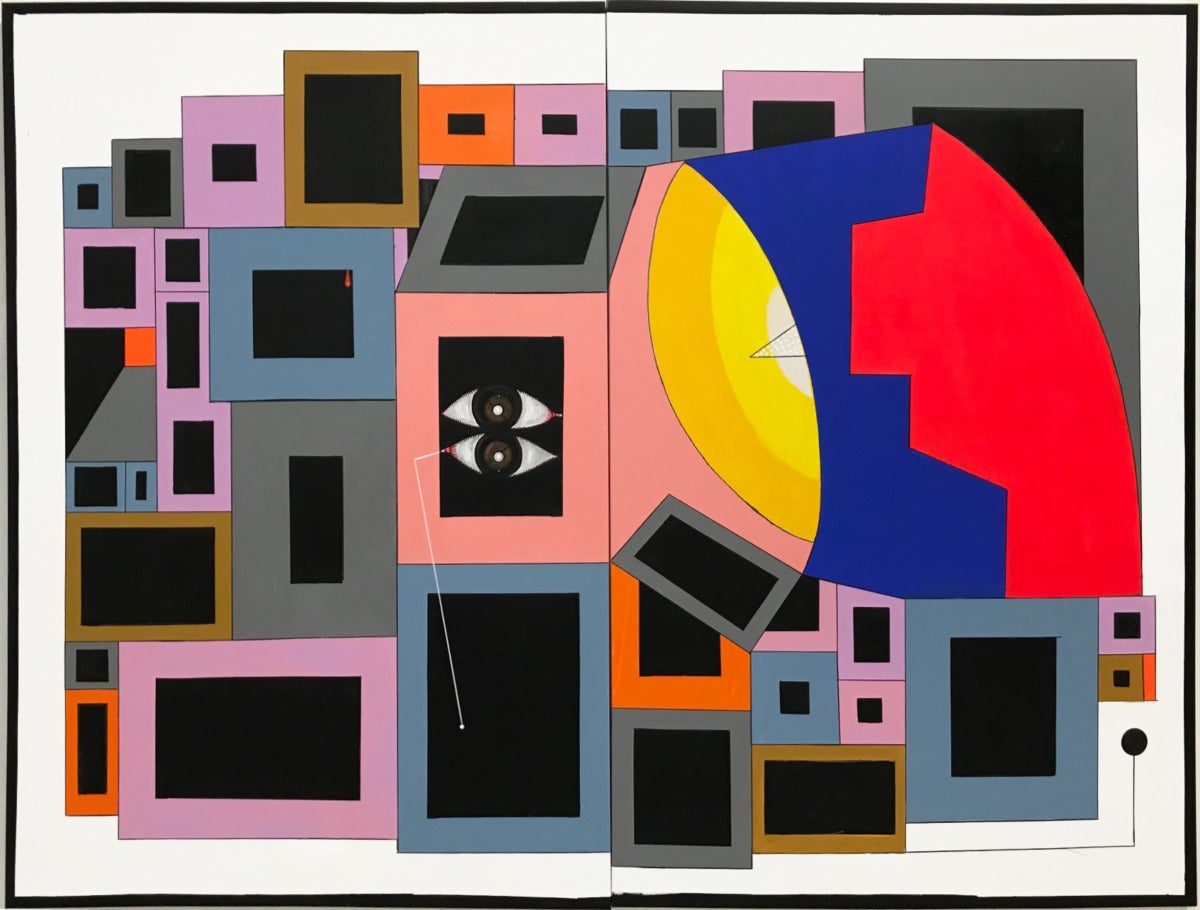

Born in Havana in 1942, where he came of age during the violence of the Cuban Revolution, educated in New York during the first bloom of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and based in New Orleans since the 1990s, Azaceta writes the “condition of being in exile is of being in two places simultaneously–physically in your place of exile, emotionally and spiritually in the place you left behind, your roots.”[1] This state of exile has made him a keen observer of American culture, and one could define much of the U.S., but certainly New Orleans, similarly—as having its spiritual roots elsewhere. Azaceta’s career began in the early 1960s during a blow to national morale: he was spurred into artistic action by JFK’s assassination and has been prolifically creating multimedia works since then.[1] Nearly a half century of this work is currently on view at the Ogden Museum, where one can walk through Azaceta’s multimedia responses to the precarious condition we find ourselves in. The survey includes earlier figurative paintings that hint at a subsequent enlivening hybridity of abstraction and figuration, such as the rueful triptych Los Misterios (1986). Azaceta’s move towards greater abstraction coincided with his relocation to New Orleans in 1992, when the city became one of his subjects. A perpetual tightrope of figuration on which Azaceta crosses the gulf of abstraction makes for daring paintings: in Hands Up, Don’t Shoot (2016), the harsh line of a divided highway evokes the straight path of a bullet and simultaneously incises the composition into triangular counterparts. Equally fragmented is the painting What a Wonderful World (1992), an homage to the birthplace of jazz, but the city’s real violence has also been a subject of the artist, as seen in the gruesome work, Real Fiction (1995), where a washed-out, vacuum-like version of the artist’s likeness is positioned to absorb actual photos of crimes and calamities.

New Orleans was mapped as an “an anti-America in which America invents itself,”[2] a brilliant delineation by the writers of Unfathomable City, A New Orleans Atlas, Rebecca Solnit and Rebecca Snedeker; as they point out, some think of that locale as the top of the Caribbean rather than the bottom of the states. Azaceta has noted the cultural continuity with his native Havana. Wherever New Orleans sits in one’s psychogeography, it’s a place that persists at the crosscurrents and polarities inherent to the project of American democracy. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 uprooted many tribes of the Mississippi River Delta; not far from the current city, descendants of the displaced and federally unrecognized Houma tribe still try to eke out a living fishing off an ecosystem decimated by pipelines and oil spills.[3] Azaceta calls to mind the continual state of displacement in the painting Evacuees (2009), where expressionistic figures drift alongside colorful, Mondrian-like grids inside of an anonymous, modernist shelter. The evacuees are marooned in a place without perspective, cast shadow, or any indication of normal physics. Instead, they are rendered from a disorienting perspective, stranded in an abstracted purgatory. Layers of historical displacement, human bondage, resource pillaging in the form of oil and sugar refining, segregation, despoiled lands and waterways, racist city planning and breached levees all intersect in New Orleans[4], and yet heartening vibrancy and cultural multiplicities that evade simplistic categorization–in short, signals of the highest potentials of the American experiment–abound there.

Azaceta has cited Francisco Goya’s “Black Paintings” as one of his references. The Spanish, Romantic-era painter also lived through war and revolution, but his darkest paintings come from a period of personal as well as political turmoil and were frescoed onto the walls of his farmhouse near Madrid. Saturn Devouring One of His Children (1819-1823), depicts a fearful god consuming his son in order to forestall the prophecy of being dethroned by his offspring. The absence of reason and intensity in Saturn’s gaze have haunted viewers across two centuries. While there are some aesthetic parallels among Azaceta and Goya–for instance in their sinuous figuration–the artists certainly align thematically: one could categorize Azaceta’s paintings as depictions of America’s annihilation of its children. I Can’t Breathe, a painting from 2020, leaves the viewer in the presence of another gaze evoking the cruelty of unjust death that has remained rooted in this country.

While a microcosm of the country’s complexities, in its oversimplified form, New Orleans is also where the frat boy next door goes to see free titties and black out on hurricanes, unaware of the jubilation to be found a block away at Preservation Hall, where the region’s jazz heritage, passed down through generations, intoxicates, edifies, and makes one feel hope for America after all. Walt Whitman, fired from a Brooklyn newspaper for expressing his opposition to slavery, lived near the offices of the Crescent; his vision of democracy persists in our collective imagination, and thankfully, in the sprawling second lines and the beautiful amalgam of cultures in New Orleans. In that city, the most celebratory and most brutally scarred layers of the American legacy survive: “the bright blessed day,” of the sleepers under the singing oak in City Park, and “the dark sacred night” of the drunk homeless kid playing Hendrix with prodigious ease on a Marigny street corner. To truly see the country’s wounds and scars, to call them out like Azaceta, is to call into being the potential to heal. Until then, this history will keep coming back to haunt us—maybe it will come in the form of a hurricane pummeling the coastline near America’s beautiful sinking city, of bayou homes tossed like tumbleweeds, or maybe it comes as the highest incarceration rate of Black men in the country. Maybe it comes in the overdosed, forgotten body we tourists turn away from in the Quarter. Our history is speaking to us in these forms and will keep rising up until we answer.

[1] Luis Cruz Azaceta. “Artist Statement.” Accessed April 13, 2022. https://luiscruzazaceta-art.com/artist-statment.

[2] Rebecca Solnit and Rebecca Snedeker. Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press, 2013, 4.

[3] Antonia, Juhasz, “Oil and Water: Extracting Petroleum, Exterminating Nature,” in Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas, ed. Rebecca Solnit and Rebecca Snedeker (Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press, 2013), 52.

[4] As seen in the creative cartography of Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas

What a Wonderful World is on view at The Ogden Museum, New Orleans thru July 24.