It was always suspicious to me that so many of the most famous narratives around gay liberation and gay rights in the United States occurred either in New York City or San Francisco. Surely, there were also gay people in New Orleans, in Nashville, in Orlando, doing the work of gay liberation, living their queer lives in communion with others. Without diving down a Wikipedia hole, the only major queer events I could name in the South were Bowers v. Hardwick, which in 1986 upheld Georgia’s sodomy laws, and Lawrence v. Texas, with the former being considered one of the worst decisions in U.S. Supreme Court history, and the latter undoing its damage in 2003. Beyond these instances, there hasn’t been much of an acknowledged queer history for the region. Two artist projects, one based in Texas and the other in Alabama, have addressed this gap by presenting queer histories, intimacies, archives, and lives across the American South with tenderness, care, and rage.

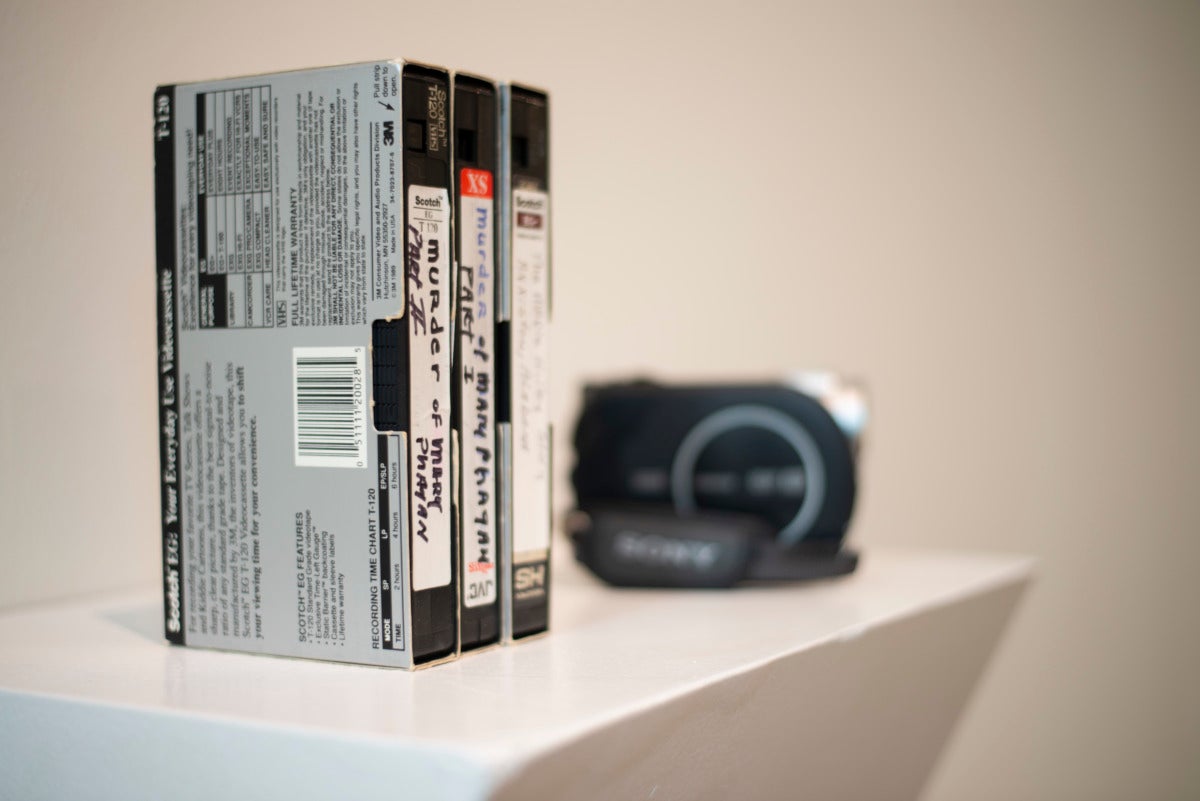

In the summer of 2021 curator Jackie Clay and filmmaker Bo McGuire mounted The Invisible Histories: See Glitter in All Black Everywhere, A Disruption by Jackie Clay and Bo McGuire at the Alabama Contemporary Art Center in Mobile. Using materials from the Invisible Histories Project (IHP) repository – created to “locate, preserve, research, and create for local communities an accessible collection of the rich and diverse history of LGBTQ life in the U.S. South – “[Clay and McGuire] are extracting hidden histories and themes within the archive, and intervening in a hope to bring visibility and recognition to the spaces created for and by Southern queer folk of all stripes.”1 Domestic objects, photographs, ashtrays, and so many of the bits and pieces of a life form the core of the exhibit, almost painful in its intimacies.

Based in Houston, without architecture, there would be no stonewall; without architecture there would be no “brick” comprises performances, installations, and other artist interventions that interrogate the relationship between politics and the built environment. A recent performance used a paved parking lot, the last remnants of Mary’s Naturally, a pillar of the LGBTQ community and one of Texas’s oldest gay bars before it closed in 2009. According to records of the ongoing AIDS crisis, some three hundred people designated Mary’s Naturally as their final place of rest. By reclaiming these spaces, without architecture, curated by Junior Fernandez and S Rodriguez, without architecture refuses the neoliberal declawing of queer activism and queer spaces and refuses to let queer riots be re-framed by late-stage capitalism into anything other than obstructive acts.

In a recent conversation with Jackie Clay, Bo McGuire, Junior Fernandez, and S Rodriguez, I spoke with them about secret queer libraries, architecture, networks, archives, and the Southern rites of queer mourning. This interview was conducted via Zoom and has been edited for clarity and publication.

Jasmine Amussen:

I’d like to start off with the broad idea of “invisible” architecture and how it relates to the built environment around us. How do you think about the relationship between built and invisible structures in your projects, and also in your understanding of queerness?

Bo McGuire:

I think it has to do with inserting my own personal family objects—which aren’t queer except for how I see them—into a larger queer archive. I see my family objects as queer because of the way they functioned in the narrative of who I am and the impossibility of archiving that sort of queer and imaginative sense. Jackie and I went to the actual physical archives [at IHP] to gain inspiration, and we had to go through all these buildings and down into this basement and go through all these people just to get a box and go through it. I don’t think queerness is compatible with having to go through these buildings and all these gatekeepers. Queerness resists being put into a basement. That’s what I think I see in y’all’s show [referring to Fernandez and Rodriguez’s series]: even though these spaces have become un-queer on the surface over time, for example Mary’s in Houston, you can still go back there and, through the spirit of queer imagination, think about what it was once there and how still lives and exists there.

Junior Fernandez:

How we begin to understand the archival juncture with queerness is through absences. In Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, the late José Esteban Muñoz theorizes queer evidence as evidence that stands against the logic of the laws of what counts as proof. There are archives in Houston that we use to inform the work in without architecture. But even within that, we came to realize a lot of this archival material was tied to white-oriented bars and gay press. These absences point to the fundamental struggle in queer representation that these works attempt to work with that rather than against it.

Bo McGuire:

Jackie and I were dealing with the physical objects that could be curated. Yes, drag queen gowns are fabulous and I love them and always will, but how do we speak to the queerness that is not known to other communities? It’s about trying to find a way to hold the contradiction that archives are of the state and are meant to be kept in-house, while also feeling a surface-level joy that queer stuff is being kept and preserved. But it’s still just going to be put into a box. When you put anything into a box, it loses its power to speak in a multivariate way.

Junior Fernandez:

That’d be my critique of Stonewall as monument, as historical theater. How do we resist this impulse towards historicity in architecture?

Jasmine Amussen:

Once it’s a monument, is it radical anymore?

S Rodriguez:

Absolutely not. Monuments are very state-sanctioned and serve a certain purpose. You can point to it and say, “Oh, this was radical way back then.” We don’t have that anymore. This encourages stagnant, non-imaginative versions of queerness. Once something is monumental, it inherently becomes a nice, little time capsule.

Junior Fernandez:

Stonewall is marked as the tipping point of the gay and lesbian civil rights movement, but when the movement becomes a monument, it’s assigned to the past and what can still be achieved is obscured. Thus, the archive is rendered a fiction. It wasn’t a brick that they threw at Stonewall. I want to say it was a shoe or a drink. There is meaning in architecture becoming a signifier of this radicality.

Bo McGuire:

The brick, the shoe, whatever is the object, the swing is where the radical queerness comes in. How do you capture that throw? I think about my grandmother’s cedar chest, which is not a queer object at all. But the cedar chest always felt queer to me because it was this special place that was always closed. No one was ever able to go into it. So, in my mind, I could only imagine the glittering things, the glittering treasures of my history that were in there, my personal history. My grandmother trusted me to go through it after her death, as if she saw my queerness and knew that I would be precious with her memory, but also be radical with it and take on her own stubborn radicality. That’s the swing for me.

Jasmine Amussen:

I want to ask about mourning because mourning is one of the things that I find defines Southern-ness. Our relationship to death and relationship to loss, whether that be a person or a story or land, I wonder how much of the queer rituals of mourning, how those appear or disappear within the archive?

S Rodriguez:

I think engaging with death, both in the built environment and through queerness is a very anti-linear time action. This reminds me of Angel Lartigue’s piece [for without architecture2], because one of the core features of their piece was collecting bacteria from the building itself. That bacterium is currently growing in petri dishes, it’s still alive. It’s one way to reanimate a corpse, take the bacteria and let it grow. A lot of the way that we engage with death doesn’t necessarily lend itself to mourning as an aesthetic practice either. Thinking of death as mutable allows for an ongoing mourning practice rather than a funeral for a life that has now ended.

Bo McGuire:

I also think about [curator] Chaédria LaBouvier. She gave a great closing speech at the 2021 South Summit in New Orleans, talking about how Southerners have always been forced to live with their dead. This is something that Southerners must deal with daily because of our proximity to the lived realities of those pasts today. She talks about how it serves the state to make the South the scapegoat, when we are the ones forced to live with these pasts, with our dead.

Junior Fernandez:

As Saidiya Hartman might put it, “How might we understand mourning when the event has yet to end?” Interestingly, there is a group of older gay men who are interested in repurposing the “Spirit of the Confederacy” statue as the guardian of the former Mary’s Naturally in Montrose; where patrons’ ashes were scattered in the early AIDS epidemic.

Jasmine Amussen:

These are symbols that have not moved. They’re extremely solid. I have yet to meet anyone who’s like, “You know what? I’m going to end the confederate flag!” There’s so much violence in it that I’m not even sure if it’s possible, but we should start thinking about it as possible. How else are we going to end this?

Bo McGuire:

One of the things I have in the show is this scrap quilt made by my great-grandmother and one of my great-aunts installed in front of the TV where my uncle John and I would watch To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar [1995]. My uncle John is a drag queen. We’ve watched To Wong Foo every Christmas while we wrapped presents together. In the beginning of that film RuPaul drops out of the ceiling in a cameo in a confederate flag gown as the character Rachel Tension.

Jackie Clay:

I have felt kind of like an interloper in this conversation so far because I’m someone who appreciates archives and I’m grateful they exist and as a curator, use them quite often. I am also very withholding personally and don’t like the idea of my objects visible. Part of what was exciting to me about working with Bo is his use of the personal object, but then making this false history.

I like duplicity and “clandestiny” in how tools around queer history contain both myth and lie. Physical spaces are vessels because they’re actively peopled and they’re pleasure centered. After the opening, Bo, some of the staff at Alabama Contemporary, and I went to Herz, which is a Black lesbian bar in Mobile, where history was made, but not documented. I think there is an undeniable need for that space, but I don’t think the space always has to be what we call a bar right now. I think it’s been all these different spaces over time, such as a radical organizing space, or labor organizing [space]. I think what y’all’s show [referring to without architecture] really brought up for me is that so many of the artists were just engaging in both ritual and labor.

S Rodriguez:

Yeah, I totally agree. And I want to also interrogate this idea of the gay bar as a place for history to be shared. Because I think a lot of the time that can be a huge myth. I’ve been out for fifteen years, since I was a young teenager. I didn’t really have gay friends. I just did gay things. I got older and met more gay people both in bars and outside of them, but I didn’t learn history from older people. I learned it from like digging around in the library. The first time I read José Esteban Muñoz was in 2011, two years after Cruising Utopia came out.

These ideas are present far beyond the gay bar or the archive, or even just older queer people. It’s a useful myth to say that you are queer, and you meet older people, and they pass down knowledge to you but… I don’t know many people with that experience. I think that’s something that maybe does happen but, in the South, for example, it’s way harder to meet older people without apps and without bars and without a transit system, without being able to go to other cities easily. I think these things are very Northern-centric ideas.

I think these physical spaces are deeply important. I just don’t necessarily think of them as being the primary exchange for knowledge or information now. They’re important because it’s important to go somewhere and be comfortable around a bunch of people that theoretically think like you or have a lot of overlapping experiences. But I don’t necessarily think that they’re these pillars of exchange anymore.

Junior Fernandez:

I think this architectural turn also provides some vocabulary that might help with such distinctions. You go on the internet or sneak out to the club at age fourteen because you’re looking for a place where you can safely rehearse and enact the self. There is an architectural longing that denotes queer space for me. It opens up a space of desire that allows us to be at home while remaining always incomplete, cruising an irreducible horizon.

Jackie Clay:

When I was first working with Josh Bradford [from Invisible Histories Project], one of his areas of research was around park design in the Southeast and how that helped or hindered gay men meeting. In Mississippi, we have all of these truck stops that were big meeting sites, and church rec centers began to function that way. There’s a whole oral history around that. A few weekends ago I was in, upstate New York, in this part of the state called the Borscht Belt where there’s a lot of practicing Orthodox Jewish communities. The folks that I was with were describing how their driveways have become these clandestine spaces, like the minivan becomes a site for radical sex acts in the middle of the Borscht Belt. This is why I like the idea of “clandestinity”; mapping that in a community is thrilling and naughty, which is my favorite ways of being.

Jasmine Amussen:

There are impact studies architects use to fight against how “criminals” use their built space in the design process—like how to get people to stop skateboarding on your corporate plaza. “This place is really, really accessible for burglars and why is that? How do we fix that?” It’s a known constant that the criminal will figure something out. The architect must address it; the burglar gets in, back, forth, back, forth forever. Because if you really want to get into a building, you’ll get into a building.

S Rodriguez:

I think that a lot of people, when they think of hostile architecture, immediately think of anti-homelessness features like spikes under a highway. But it also applies to what Jackie is talking about, and what Jasmine, you’re talking about in terms of park architecture. Homosexuality was also a criminal offense until recently. That often gets lost in the conversation about hostile architecture.

Junior Fernandez:

I like that in relation to Alejandro Penagos and Juan Betancurth’s work [for without architecture3], except here the queer body is the tool through which this hostility can be unbuilt.

Jackie Clay:

I did want to ask S and Junior about your process because I was really impressed with the real variety of types of performance. Some folks had very durational and endurance works and then some folks are completely irreverent and naughty. How did you kind of enter into the process?

S Rodriguez:

We only had a loose idea of what the artists would do, and we stayed in touch and kept having conversations with them. Most of the artists had certain pieces that weren’t relevant, but they created new ones for this show that were either tangentially related to some of their old work or fed off older pieces of theirs. We didn’t ask people for certain work, in terms of having them create things for the show.

Bo McGuire:

Yeah, I was just thinking about that. That how do you hold space? How do you still do the work of archiving or of attempting that? Of whether you’re preserving something or trying to capture the energy of something? I guess it’s just the… I want to hold space for revering the part of us, as archivist or whatever, as curators, as makers, about everything that you can’t get. Everything that inevitably will fall through the cracks or not be spoken about. And yet we labor at it anyway—that feels very queer and very Southern to me.

1Exhibition text for The Invisible Histories: See Glitter in All Black Everywhere: Archiving Southern Queer Histories, Alabama Contemporary Art Center, July 9 2021 – October 9 2021.

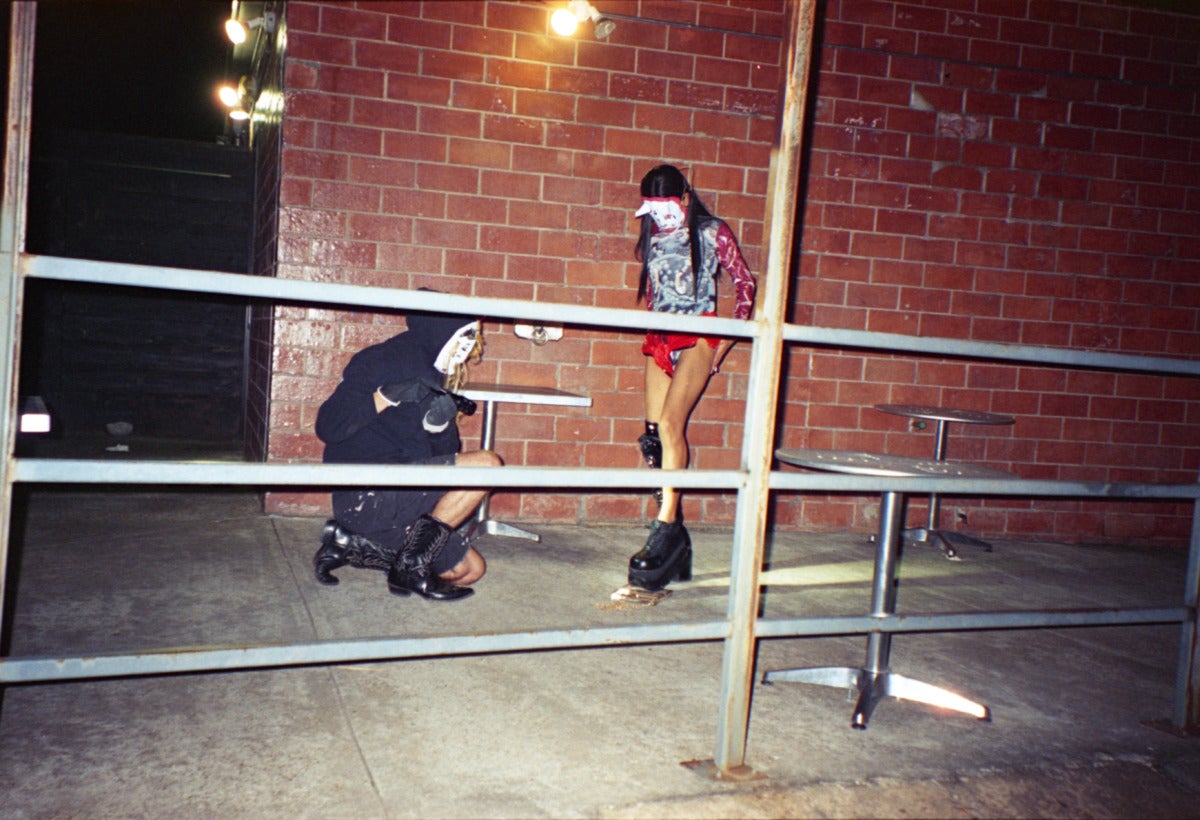

2The title of Lartigue’s work to excavate is to destroy “refers to a phrase used in archaeology, in which the act of excavating the past is at the same time always destroying it in some shape or form. This phrase inspires the performance as a type of burglary at nighttime, where a team of burglars enter the site of what was once Mary’s Naturally. The burglars are not interested in breaking inside the building but instead ‘steal’ the microorganisms living on the surface of it.” See Angel Lartigue, “to excavate is to destroy,” Angel Lartigue, 2021, https://www.angel-lartigue.com/to-excavate-is-to-destroy.

3 For without architecture, there would be no stonewall; without architecture, there would be no “brick”, the Betancurth and Penagos chose to work with the sonic elements of a bell, with the bell functioning like a call or an alert that invites people to congregate. In PARÁBOLA II, the artists appropriate the bell, a common symbol within many cultures, to gather the voices that have been and continue to be systematically silenced.

This essay was part of Burnaway’s yearlong series on Nodes and Networks.

This essay was originally published in our 2021 print annual, Treasure. You can purchase Treasure on our shop.