“Therefore, good Brutus, be prepared to hear.

William Shakespeare, Julius Caesar: Act I, Scene 2

And since you know you cannot see yourself

So well as by reflection, I, your glass,

Will modestly discover to yourself

That of yourself which you yet know not of.”

Vivian Maier was not Mary Poppins with a camera. Nor was she “the mystery woman” or “spy” that she sometimes claimed to be. Vivian Maier was a serious and dedicated photographer, plain and simple.

In the brief span of time since the 2007 discovery of Vivian Maier’s abandoned cache of thousands of photographs, most in the form of unprinted negatives, she went from total obscurity to being the object of significant media attention, cultural speculation, and artistic controversy. Her images have been published as books, exhibited in galleries here and abroad, and featured in at least three films, most notably the recent release Finding Vivian Maier, a pseudo-documentary directed by real estate agent John Maloof, principal owner of the Maier trove. He is also the person with the most to gain. Maloof appears in and narrates the film and functions as its chief propagandist. He creates a mysterious character out of Maier’s eccentricities, and dances around the fact that the photography establishment, especially major museums, has shown little interest in her work. He touts her work’s popular appeal, and avoids anything that may question the integrity of his venture. Another Maier documentary, The Vivian Maier Mystery, was made by the BBC. After seeing the first, I downloaded and watched the second, which is rather different and raises points glaringly absent from the Maloof film. For starters, it’s not about John Maloof, it’s about Vivian Maier. It led me to consider Maier not as a nanny with a camera but as an American urban photographer in the middle of the 20th century. It’s a more interesting story.

Little is known about Maier’s private life, which would be just fine with her. She was obsessively secretive and kept her private thoughts and personal artifacts hidden from view and locked tightly away. The obituary facts that are commonly used to explain an ordinary life are missing. She relished anonymity and solitude, preferring to take her secrets to the grave. In death, however, she is being haunted by the unwelcome specter of public scrutiny and fame. Her emotional crypt has been wrenched and pillaged, a schizophrenic mythology concocted from the shards: Weird Child-Choking, Man-Hating Nanny May Be Greatest 20th-Century Street Photographer. Maier would have hated the prying eyes of intrusion brought about by her disinterment. But it appears that the cloistered life that she preferred is today seen as an outdated lifestyle foreign to the 21st-century selfie-obsessed, wannabe star-fuckers that we have become. So rather than letting Maier rest peacefully, we have resurrected the secluded hermit as a celebrity brand.

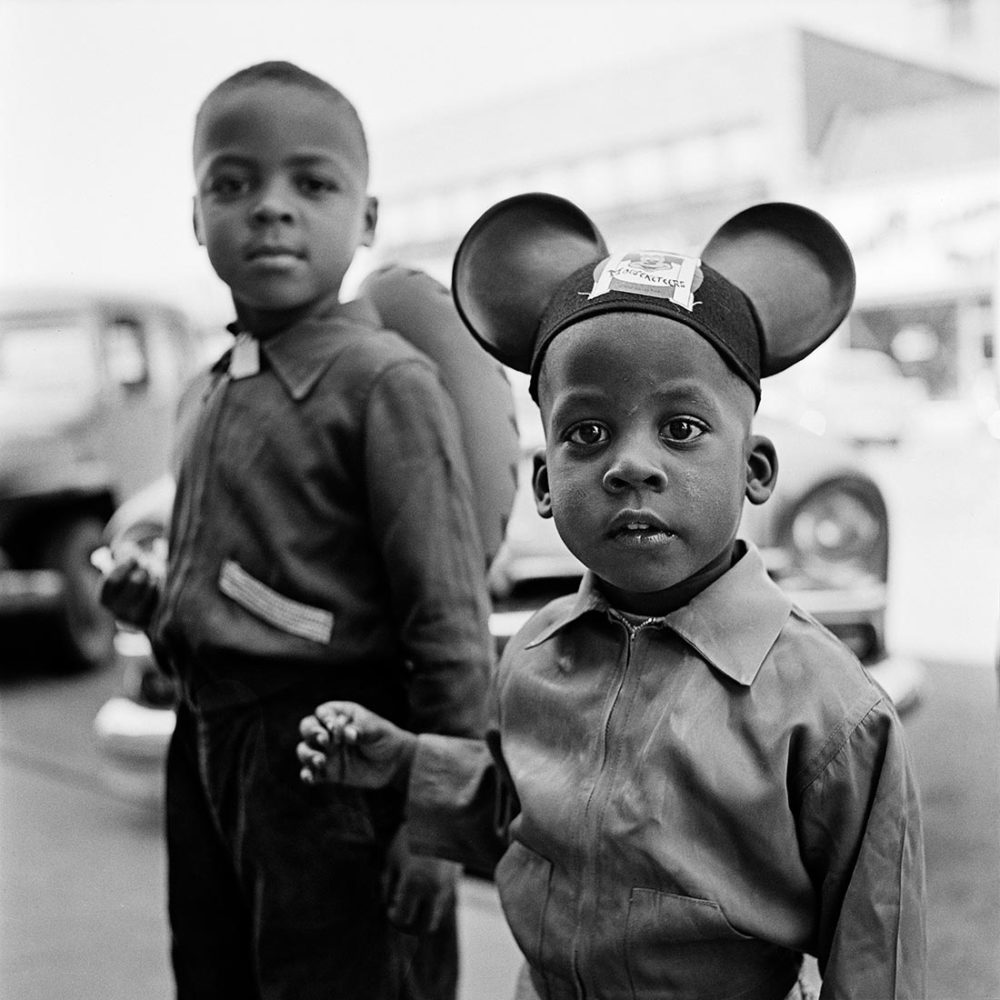

Maier came to photography at, or near, the apogee of classic street photography in the ’50s and ’60s. In many respects, it was among the more interesting periods in the history of photography in America. In the years following WWII, there was an explosion of creative energy that challenged the status quo in the arts, including photography. The streets were already fairly crowded with photographers when Maier took to them. This emergent community included a number of photographers who gained considerable recognition, many whose reputations have endured: Robert Frank, Lisette Model, Aaron Siskind, Diane Arbus, Harry Callahan, Imogen Cunningham, and W. Eugene Smith. Photojournalism had been the dominant model, but a number of photographers like Siskind, Sommer, and Callahan, turned the camera inward and chose poetry over prose.

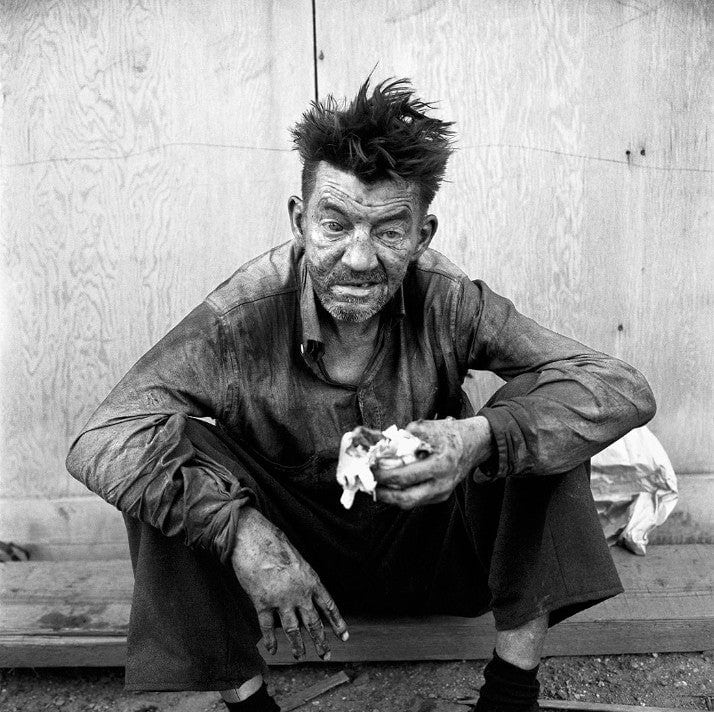

Maier’s photography was not sui generis. Today, her images feel familiar and have a populist appeal. Many of them echo the work of well-known women photographers from the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s, notably Lisette Model, Diane Arbus, Bernice Abbott, Ruth Orkin, Margaret Bourke-White, Marion Post Walcott, Rose Mandel, Lotte Jacobi, and Helen Levitt. It is fair to assume that some of the images made by these women would have become known to Maier, who, by the late ’50s, was seriously committed to documentary photography. Similarly, the need for solitude may have seemed out of character among nannies, but it is practically a requirement for a street photographer who works in isolation, anonymously and invisibly. Maier’s eccentric ways and antisocial attitude shouldn’t be allowed to define her. I’ve known many artists over the years, myself included, who have demonstrated behaviors not wholly dissimilar from Maier’s.

By the end of her life, Maier had produced more than 100,000 film negatives. A reclusive and eccentric nanny leaving 100,000 photographic negatives behind would indeed seem oddly mysterious. But to a photographer like Maier who walked the streets of great cities like New York and Chicago for decades, shooting 100,000 frames of film is more like a good start.

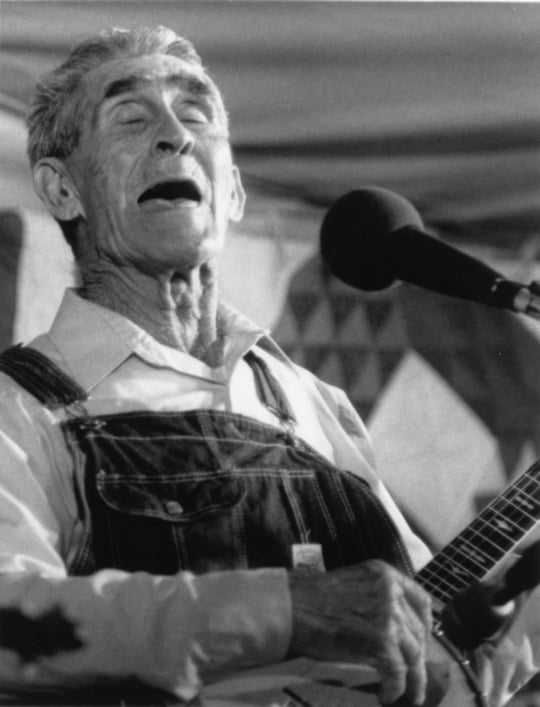

Street photography is broadly defined to include highly personal and unconventional artistic expression drawn spontaneously and impulsively from observing daily life. Think Robert Frank, Diane Arbus, or Harry Callahan. Strict documentary photography, on the other hand, has a premeditated agenda, intended to bring attention to human and social conditions, hoping to improve conditions and change society. The two approaches are similar, but the driving impulses are quite different. A survey of the Maier images made public to date places her work handsomely in the social documentary genre. Her images are often artfully seen, some to very powerful effect, yet they reveal minimal interest in the modernist experimentation of their day. In general, her images conform predictably to the prevailing aesthetics seen in period publications such as Life, Look, and US Camera, or books from the 1950s like the famous Steichen survey The Family of Man.

There is also good reason to believe that Maier had opportunities to visit influential exhibitions, such as “Five French Photographers” at the Museum of Modern Art in 1951, which included famed street photographers Cartier-Bresson, Brassai, and Doisneau. I learned from Pamela Bannos, distinguished senior lecturer at Northwestern University, who is writing a book on Maier, that she photographed Salvador Dalí in front of MOMA while that exhibition was up. Over the years, Maier purchased a Rolleiflex, a Leica, an Exacta and a Zeiss Contaflex, all professional level, expensive, top of the line cameras, carefully chosen. In the late 1950s, that took a considerable commitment of resources. Even being aware of these brands is telling.

Vivian Maier didn’t work in a vacuum, but we’ll never know just how aware she was of goings-on in photography circles during her productive period. Certainly, selecting fine cameras would have required research and consultation. And we can tell much from the images that she made. Her photographs were historically informed and done in an established style. She seemed aware of the ethos of working the streets. Her choice of subject matter was eclectic and unambiguous. She had very good instincts and saw things photographically. And somwhere, somehow, she found photography and it changed her life. So, why wasn’t her photography noticed? That answer is a bit complicated. In the 1950s, there was very little interest in serious photography outside of the pages of photo magazines—collectors and exhibition opportunities were few and far between. An amateur with no connections had little chance for recognition.

To whom would Maier have shown her work? She’d have to have found someone knowledgeable and sophisticated about photography. The Fort Dearborn-Chicago Photo Forum has existed since 1895. The Art Institute of Chicago began collecting photography in 1945. No one knows if she was aware of these entities. There was a new photography gallery in NYC in 1954 where she might have gotten a hearing, if they’d have granted her one. Called Limelight, the gallery was already inundated and turning down requests for portfolio reviews from across the country. By the mid-’50s, the secluded Maier had serious company on city streets; “stalkers” with cameras, seduced like her by the urban hum, each one invisible to the others.

In 1954, Limelight gallery opened inside a Greenwich Village coffee house. At the time, it was the only one in the country. The owner, Helen Gee, was well informed and knew all the leading photographers of the day: Steichen, Imogen Cunningham, Stieglitz, HCB, W. Eugene Smith, Strand, and Weston, legends all. She exhibited a “who’s who” of midcentury photography. Some even sold prints for princely sums ranging from $10-$40 (Ansel Adams’s went for $60!). A disheveled Robert Frank hung out there, said Gee in her memoir Limelight: A Greenwich Village Photography Gallery and Coffeehouse in the Fifties : A Memoir, carrying his Leica in a crumpled paper bag and fretting over the Guggenheim Fellowship application that (thanks to Walker Evans) eventually enabled him to travel across the country and produce his landmark book The Americans. The influential New York Times photography writer Jacob Deschin advised Gee. Stieglitz’s lover, Dorothy Norman, exhibited portraits she and Stieglitz had done of each other during their time together, hoping to piss off Stieglitz’s wife, the painter Georgia O’Keeffe. Photographers from across the country sent unsolicited work hoping for a show. A list of her exhibitions reads like a history of photography. In the 1950s, this was the environment for those like Maier who had discovered in photography a means to better understand the world they lived in. We cannot assume that Maier was the only dedicated photographer whose work went unnoticed in a dank basement or dusty storage locker.

For some photographers, the 1950s were a dangerous time. Those were the days of the House Un-American Activities Committee and the Army-McCarthy hearings trying to flush out commies, real or imagined. Artists with accents and foreign-sounding names, like many photographers, were highly suspect. In the 1940s, a controversial group, the Photo League, was founded to encourage photographers to document social ills and inequities in American society. Many top photographers became members. But the league had been started by the Communist Party and in 1947 was blacklisted as a subversive organization. It cost Siskind a teaching position years later. Adams belonged but smooth-talked his way out of trouble. During his Guggenheim trip, Frank was arrested in Arkansas. He had a foreign accent and a camera. They thought he was a spy. The league promoted the kind of socially conscious photography that Maier preferred. Could she have been aware of the Photo League’s history? Might she have thought that the US Government was suspicious of people who did what she did? Was that why she sometimes called herself a spy?

Vivian Maier has entered the popular culture. Some version of her story has now been told worldwide, on CBS, CNN, and BBC TV, in Time and Smithsonian magazines, as well as Maloof’s big-screen infomercial. In its coverage of the Maloof film, the Daily Beast asks, “What exactly makes (these photos) great, or how singular or imitative are they? … The film almost bullies us into accepting their greatness.” Despite the best efforts of a marketing campaign that is trying to convince the buying public that Maier was an unknown genius whose discovery puts her near the top of a list of photographers that includes Atget, Robert Frank, Joel Meyerowitz, Diane Arbus, Lisette Model, Harry Callahan, Leon Levenstein, Ruth Orkin, Aaron Siskind, Cartier-Bresson, Walker Evans, Robert Doisneau, and Brassaï, just to name a few, the jury is still out.

Most of the Maier materials are owned by Maloof and Jeffery Goldstein, a Chicago collector who owns approximately 12,000 of Maier’s negatives. He is also making prints for purchase from his portion of the negatives. The new owners are eager to have their trove accepted into the photographic canon. A blessing from the establishment would complete the alchemist’s ritual and turn the silver-halide into gold.

Where Maier fits in the canon of street photography, if she fits at all, is not agreed upon by curators or serious collectors. And though the public has been smitten by the colorful tale of a crotchety nanny who turns out to be an artist in the rough, scholars and historians see things differently. The curators and collectors who agreed to be interviewed for this article did so only if they remained anonymous. Each was familiar with the work and the campaign to market the prints. None expressed interest in adding Maier’s work to their holdings. Most find distasteful the aggressive and dubious PR campaign intended not to celebrate Maier but to create a market for posthumous prints of unproven worth. The prints are being made by strangers with no knowledge of which images she valued most, or of how she would have wanted them printed, both ethically questionable acts. The quality is inconsistent; the prints, impersonal.

I spoke to one collector who scolded a dealer for offering for sale such a glaringly poor print. Others feel that prints being made without her notes, or her voice in any form, will never accurately represent her personal vision, issues of great import to a collection. Nothing is known about her feelings regarding these critical print-making issues. In Maier’s day, print quality mattered. It still does. We can never know which images she felt were her most successful efforts, or if she felt she succeeded at all? We don’t know why she started, or why she stopped. The new owners have had to make up a story, a compelling yarn that will distract us from their inability to speak authoritatively about the photographs they are selling for $2,000 per. Maier has been turned into a cartoon character so we can be entertained and distracted by the backstory while not being told the real story of Vivian Maier, photographer.

If Maier’s work had been found thirty years earlier, this wouldn’t be a story. In 1977 there was no internet, few photography galleries or college programs, some workshops, no FotoFest-style portfolio reviews by prominent gallery owners, and no tightly wound high dollar photo-marketplace hungry for the next big thing. It is unlikely that unclaimed negatives found in a local storage locker in 1977 would have gotten much notice.

What we know about Maier we know from her pictures. Her messy eccentricity didn’t prevent her from being a disciplined photographer or from making good pictures. And if you think she was strange, remember that photographer Arthur Fellig, a.k.a “Weegee, the Great,” slept in his clothes … in his car … and didn’t often bathe.

Perhaps someday a competent person will search gently through her images looking for the soul of Vivian Maier. It will be found where it often is, in her most personal and intimate images, and in those places that show us where she looked when no one was watching. She deserves at least that much.

An exhibition of Vivian Maier’s photographs, Summer, will be on view at Jackson Fine Art in Atlanta, July 10 through August 30.