Stacy Lynn Waddell’s artwork was hiding in plain sight when I visited with her at Elsewhere in Greensboro, North Carolina, which occupies a three-story former thrift store owned by Sylvia Gray, grandmother of co-director George Scheer. We sat on a vintage couch in a worn yet genteel upstairs room teeming with artwork. For the residency at Elsewhere, artists create work for the space using things they find within the building, drawing upon the inventory left behind when the thrift store closed. Other than being loaned out for temporary offsite exhibitions, their work remains at Elsewhere as a part of its permanent collection.

Projects often have improved the space or catered to its inhabitants, such as window shades titled Memory Catcher by Densie Driscoll (2011), made from the loose pages of old books, folded into lovely, elaborate panes. Elsewhere is a stronghold of whimsy in an arts-friendly city. The building’s exterior blends into a neighborhood of one- and two-story brick commercial buildings, yet working swings hang in the front display window that can open to function as an on-street stage. Inside, elaborate collages made by former artists-in-residence and other artists embellish the walls and old books fill worn shelves in inviting stacks.

Waddell, who earned her MFA at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill in 2007, says she felt lost for the first week of her month-long residency in October. As she acclimated from working in her solo studio space in downtown Durham to the communal atmosphere of Elsewhere, her self-reliance loosened, opening up to the intimacy that develops between residents, staff, and interns.

Six residents at a time (totaling 50 each season) work, sleep, and prepare communal meals in a centrally located kitchen behind the main entrance. Their production becomes framed, on multiple levels, by their surroundings, and the tenor of their daily lives revolves as much around community as art. It brings social practice and decorative art on a par with fine art, as many projects improve the living space with repairs to the crumbling walls and organizational devices, such as the Wood Library designed and built by Paul Howe and Colin Bliss (2013) to both organize and display wood scraps.

In a room as enchanting as a Wes Anderson film set, I had no idea what Waddell made until she pointed it out: a small, square, wooden table at the center of the room. If it had been placed on a pedestal and professionally lit in a white gallery space, the piece would have had a different effect. But here, her work integrated seamlessly into the setting.

Appropriately for Elsewhere, indistinct divisions between artistic form and function parallel meanings that lay at the center of Waddell’s practice. Waddell leverages decoration and content to question tidy understandings of social and artistic points of American history, such as Manifest Destiny and the slave trade. She redoes landscape paintings by Hudson River School painters, such as Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) and Robert Duncanson (1821-1872), meditating on how the utopian scenes, constructed so that we can’t help but enjoy ourselves, romanticize a nation established by violence and white supremacy.

Waddell recreates the sublime scenes through burning, usually a destructive action. The works have relatively muted palettes because, rather than applying pigment, Waddell systematically and carefully damages the paper to make her marks. Her recreations are both tributes to 19th-century styles and criticism of their contrived nature and glossing over, literally, of historical facts.

Her work is subtle, and decoration is one of her consistent devices. The magnetic pull of of glittering surfaces and calligraphy comments on American culture, both historic and popular. One of Waddell’s primary instruments is a brand, a tool that was used to mark human property. She uses the letter “b,” choosing it for the emphatic role it plays in language and and for the sound it makes as we say it. To create effects, such as receding space, shadow, and light, she also experiments with acid, burns holes in or tears the paper, varies the pressure of the brand on the paper, and directs the heat from a blow dryer onto the paper to burn the paper. At times, she leaves the focal point of a painting—a mountain range, for example—as an empty void, by leaving the outline in place but omitting what shadows or trees may have been in the original work. She may fill it with shimmering, delicate gold leaf that also has a flat effect. Her alchemy leads to sensitively rendered scenes that retain the beauty of the originals, rendered entirely in tones of brown.

Waddell’s body of work also includes installations exhibited in group shows at the North Carolina Museum of Art (0 to 60, 2013) and the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Southern Constellations, 2011). In both locations, she wallpapered the gallery walls with a lush tropical backdrop. The clear blue sky, sandy beach, and palm trees are inviting in a trite way, especially as the same scene repeats insistently over the span of two walls, stressing its manufactured quality.

On top of that, she then hung her framed works of recreated 19th-century art, including the landscapes. Her works interrupted the coastal vistas, operating as points of entry, or exit, and referring to the Middle Passage of the slave trade. The result expresses both her admiration for 19th-century paintings and what subjective historic records they are.

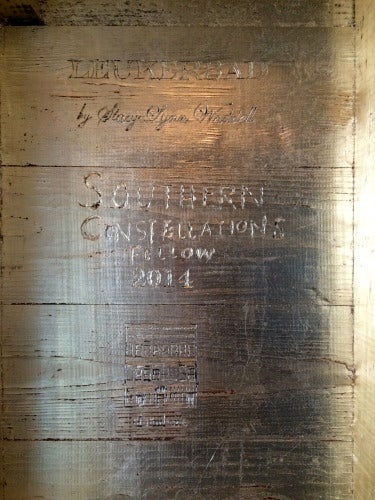

At Elsewhere, Waddell transformed a worktable by covering it entirely in gold leaf. As hinted earlier, in subtle lighting, the worktable still appears to be a simple space on which to work. Upon closer examination, the rich, lovely glow of gold leaf is visible, but the table retains all of the scuffs, dents, and other marks it had when she found it. On the bottom of the table, she used a wood-burning tool to carve her ornate signature, the date, and the title, Leukerbad.

Leukerbad is a village in Switzerland that James Baldwin visited in 1951. There he found refuge, made progress in his writing in a way he hadn’t for years, and had a profound realization about racism. He was the only black person in an all-white village, a big shift from his usual New York City milieu. He experienced a bald, direct form of white supremacy where people openly stared and children shouted at him as he walked down the street. Relations between whites and blacks in America were by contrast more complex and nuanced. The contrast and distance from his familiar experience helped crystallize Baldwin’s understanding of racism, and he wrote about it in his essay “Stranger in the Village.”

By aligning her work with an author, Waddell acknowledges her emotions, but the specifics remain opaque. Her inspiration for Leukerbad is also deeply personal. She brands her works on paper at a tabletop surface in her studio, and the wood bears the residue of many marks. Also, when reading the book Pilgrimage by Annie Leibovitz she was struck by an image of Virginia Woolf’s writing desk, as it appears remarkably similar to her branding board. Woolf made many ink and perhaps tea stains over time, and the marks do not tell us what Woolf wrote, but how often she wrote. It is endurance and creativity made visual.

Waddell’s Leukerbad similarly refers directly to the creative process, the vulnerability involved, and to the precious gift of being in a position to make things. The thin sheaf of gold is delicate; it will be damaged when it returns to the collection and is used. In preparation for its use, the artist made a repair kit with instructions to accompany the table.

Waddell acknowledges the importance of the collection to Elsewhere by covering her offering in gold, a material of inherent value. The fact that projects do not leave the building makes the place, over time, seem “dear” or precious and intensely self-referential. The layer of value on a simple, small worktable pushes this point.

Tables are communal; we circle around them to eat, work, socialize, and relax. They help define interior landscapes, and our memory of time spent in a specific place. Leukerbad references racial relations, but it also speak to hope, to renewal, to the rhythms that bring us together again.

Waddell’s work is currently included in “Area 919,” a group exhibition of Triangle-area artists at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, January 24-

April 12.

Shana Dumont Garr is a writer, contemporary art curator, and the director of programs & exhibitions at Artspace in Raleigh, North Carolina.