The name José Antonio Aponte is little known; Aponte, the man, was a force of nature or, perhaps more appropriately, a force of humanity. A free Black man in Cuba, as well as a carpenter and former soldier, Aponte was publicly hanged and then beheaded in 1812 by Spanish authorities on the charge of fomenting a rebellion against the slavery that enabled Cuba’s lucrative sugar plantation economy. Aponte’s execution and the subsequent display of his severed head in a cage posted outside his home sent a clear message from the colonial rulers: insubordination or the threat of such from subjugated populations in the Caribbean would be met with swift, violent retribution.

In searching Aponte’s home, the Spanish found an astonishing object, what they described as a “book of paintings”: a bound compendium of sixty-three densely illustrated pages that depicted dark-skinned people as kings, warriors, and philosophers across a breadth of eras and contexts, from the garden of Eden to ancient Greece and Ethiopia. Where Aponte, who almost certainly could not read or write, gleaned this vast historical and cultural knowledge remains a mystery verging on a miracle, explained Edouard Duval Carrié, artist and co-curator of the new exhibition Visionary Aponte: Art and Black Freedom at the Vanderbilt University Fine Arts Gallery, which has traveled to NYU, Duke, Havana, and Santiago, and will continue on to Harvard before heading back to the Caribbean. At the opening, Carrié gave context for how the exhibition came to be.

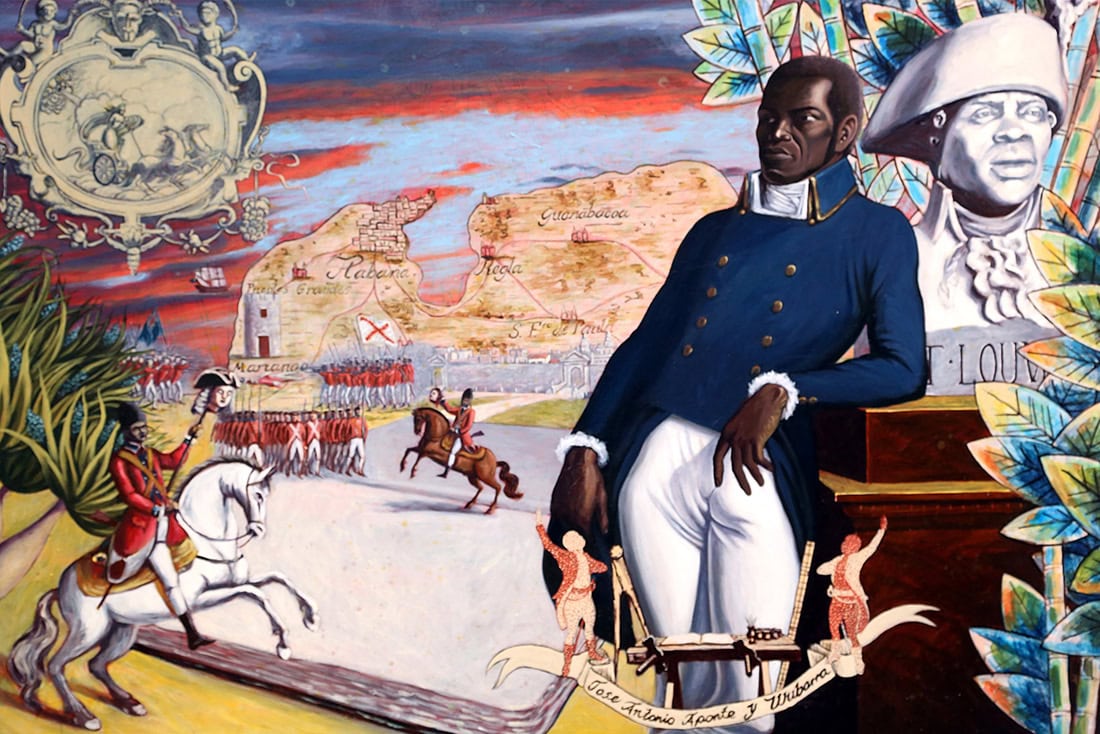

Just before his murder, authorities forced Aponte to explain each image, so though the actual “book of paintings” is lost to time, it lives on in the ekphrastic transcription of that interrogation, which can be found in full at Digital Aponte, an accessible repository of scholarly research conducted by NYU Professor Ada Ferrer and art historian Linda Rodríguez. Today, twenty artists, most of them Afro-Caribbean, have further amplified the book’s—and Aponte’s—power by resurrecting some of its pages (or láminas) in their own artworks based on self-chosen passages from the transcription. These artists have honored Aponte’s vision of a world defined not by totalizing elite whiteness, but by a social structure and cosmology that reimagine history and the present through the lens of Black power.

When asked, Aponte cheekily claimed the book was a present for the king of Spain, Juan Carlos I, to educate him on his Black constituents. But we also know that Aponte intended it as a kind of pictorial instruction manual for his fellow slaves to rise up and overthrow the conditions of their servitude. One work in Visionary Aponte, Júbilo de Aponte—a monumental, multi-panel, altar-like piece in mixed media by major Cuban artist José Bedia—portrays a procession of slaves marching together in the same direction toward freedom. The piece employs black geometries and arcane symbols to gesture toward some of the many belief systems Aponte incorporated into his book, woven together with black ribbon in a dark take on the white ribbon that authorities were said to have confiscated from Aponte’s home. Vanderbilt curators affixed Júbilo to the full wall it requires to be viewed properly, though a couple of other paintings were given short shrift in corners or behind the entryway desk, presumably due to space constraints.

El Roble Noble, a stark, textural sculpture by the Cuban-born artist Emilio Adán Martínez, depicts Aponte’s ideals more simply. The artist uses a hefty cross-section of an oak tree sealed on top by perpendicular steel bars to evoke captivity and the darkness of being unfree. “I used oak because it symbolizes strength,” said Martínez. “That’s my feeling of who Aponte was: a pillar, even through the darkness.” Peer down into the tree trunk and you’ll see a floor of glittering black sand, reminiscent of the sugar that drove Cuba’s economy.

Several pieces incorporate Aponte’s fascination with the stars and the cosmos, like Aponte, a series of wood panel paintings by the Brooklyn-based artist Teresita Fernández, who uses pyrite, oil, graphite, and gold to evoke West African alchemy traditions with which Aponte may have been familiar. Aponte saw the planets and their environs as places exempt from colonial oppression, where personal power and expression could be reclaimed. Renée Stout’s Book of Paintings, a series of recreated pages, foregrounds a glowing, red moon-like orb, and several mystic symbols that resemble spells or invocations to gods, summoning their power for Aponte’s radical ends.

Other works engage more explicit portraiture. The Guadeloupean artist Joelle Ferly’s mute digital video, Revealing Aponte, resurrects Aponte via a chaos of small black dashes that gradually assemble into the contours of Aponte’s face, then dissolve back into abstraction. The forceful, mask-like visage in Juan Roberto Diago’s Terraco looks fearlessly back at the viewer; its blunt black-and-white palette mocks Fidel Castro’s notorious claim that racism in Cuba had been solved. Alexis Esquivel, a Cuban painter, reimagines one of Aponte’s self-portraits onto a famous 1797 painting by Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson, Like fire burns in living flames. Here Aponte’s face is placed onto the figure of Jean Baptiste Belley, a former slave from Sainte-Domingue who served as a member of the National Convention during the French Revolution, the first Black deputy to do so. Aponte reclines in a relaxed pose, confident of his power, surveying the realm, watched over by the shade of the Haitian revolutionary Toussaint L’Ouverture. The large scale of the painting imposes itself upon the viewer, transmitting Aponte’s self-assured gaze. It is one of the exhibition’s most arresting displays.

The exhibition also highlights a contribution by María Magdalena Campos-Pons, the Cornelius Vanderbilt Chair of Fine Arts at the university, whose Five Apparitions from her series “A Peace of Sea” resembles a watery blue wash in which abstracted figures are held up by root- or thread-like structures, their mooring in the great sea of history, a poignant metaphor in Caribbean lore and memory.

One final, striking fact about Aponte: he fought in the American Revolutionary War, on the side of the colonies. His history is our history, not because he fought for us, and not to be subsumed within a greater narrative, but rather to remind us that revolutionary movements in the Caribbean, particularly the Haitian Revolution, define American history as much as those within our borders. Aponte himself embodied a mind without boundaries, imagining liberty for the oppressed through his ideas and actions. The exhibition devoted to his vision itself constitutes an act of justice worthy of bearing his name—and a testimony to the unkillable spirit of freedom.

Visionary Aponte: Art and Black Freedom continues at Vanderbilt University’s Fine Arts Gallery (1220 21st Avenue South, Nashville) through March 8.