A home takes up a role much more precious than just shelter. It is a place for recreation, for pleasure, for creativity, for safety. In 1927, Le Corbusier designated it a practical “machine for living in,” while his contemporary Eileen Gray rebuffed this and termed it a “living organism,” perpetually adapting along with its inhabitants.1 Both key figures of modernist architecture, their pedagogies are melded in the designs of another vanguard in their field, Amaza Lee Meredith. Meredith’s best-known design, an International-style home called Azurest South, is minimal and without ornament, but its interior is sensual and intimate, ripe for a luxurious, well-lived life. The house, constructed in 1939, sits on the edge of campus at Virginia State, a historically Black university in Petersburg, Virginia. With an asymmetric, curving facade painted stark white and trimmed with bright blue-green piping, it stands out as peculiar in an area populated by Colonial Revival houses, credited as one of the state’s earliest modernist homes. Meredith lived there with her partner, Edna Meade Colson, for forty-five years. For a Black queer couple finding its footing at the onset of the twentieth century, such a space would offer a near fantasy; Meredith’s innovation made it a reality.

The pair met in 1915, on the same campus where they would later share their life, when the university was called the Virginia Normal and Industrial Institute.2 Meredith was pursuing her elementary school teaching certificate, and Colson, seven years her senior, was an instructor. Afterward, unable to enroll in graduate programs in the Jim Crow South, they both matriculated to Columbia University’s Teachers College in pursuit of advanced degrees, each relocating to New York City at the apex of the Harlem Renaissance.3 During her years in New York, spent perusing galleries, attending lectures, and painting, Meredith kept in close contact with Colson, testing the waters of their affections. As they navigated queerness in the early twentieth century, their early exchanges paint an image of confusion and trepidation about the implied intimacy they shared in their early meetings. (“I wanted to be with you yet I was ashamed, I went to your room so often . . .” Meredith wrote.)4 Letters from Meredith’s archive elucidate a slow-burning romance as the two explored their feelings on paper. “I wonder if any girl has thought or rather felt towards another as I feel towards you,” Meredith pondered. “Perhaps you do like me some, do you? Our friendship has been a strange one, and it may seem strange to you if I were to write and tell you how I feel, but I shall not do that. But Edna, have you the least idea how much you mean to me?” Sweetness drips off the pages, a relic of queer intimacy told in private.

As I perused these snippets while researching Meredith, my fascination with her artistic accomplishments became inextricable from my awe over her great, groundbreaking love. I became familiar with Meredith in 2020 and immediately began researching and writing about this undersung designer with whom I felt an instant affinity, finding connectivity to her legacy as a Black woman artist. But it was not until this summer that her letters began to mean so much to me. Queer, in love, and attending my first residency away from home while researching and writing about Meredith, I pored over their letters, relishing in their tenderness. I shared them with my partner as we maneuvered the early months of a new relationship and found parallels to our own romance. I was both heartsick considering how much Meredith and Colson sacrificed to be together in the face of fear and potential alienation and spellbound peering into their near-lifelong romance. Alongside all they accomplished as trailblazers in their communities, their union was extraordinary.

After decades of correspondence, coy flirtation turned boundary-pushing innuendo, and a broken engagement with a man on Edna’s part, the pair decided on cohabitation. Meredith returned to her alma mater in 1935 to establish Virginia State’s fine arts department, and Colson joined her later to serve as director of its education department. In 1938 the couple jointly signed the deed for a one-and-five-eighths-acre plot on Boisseau Street, twenty-three years after their first encounter as student and teacher.5 The construction of a home to share solidified something rare at the time: a private space for two women to be in love, shrouded from public scrutiny. This materialization of their affections demarcated their independence as modern, working women living together in lieu of heteronormative domesticity.

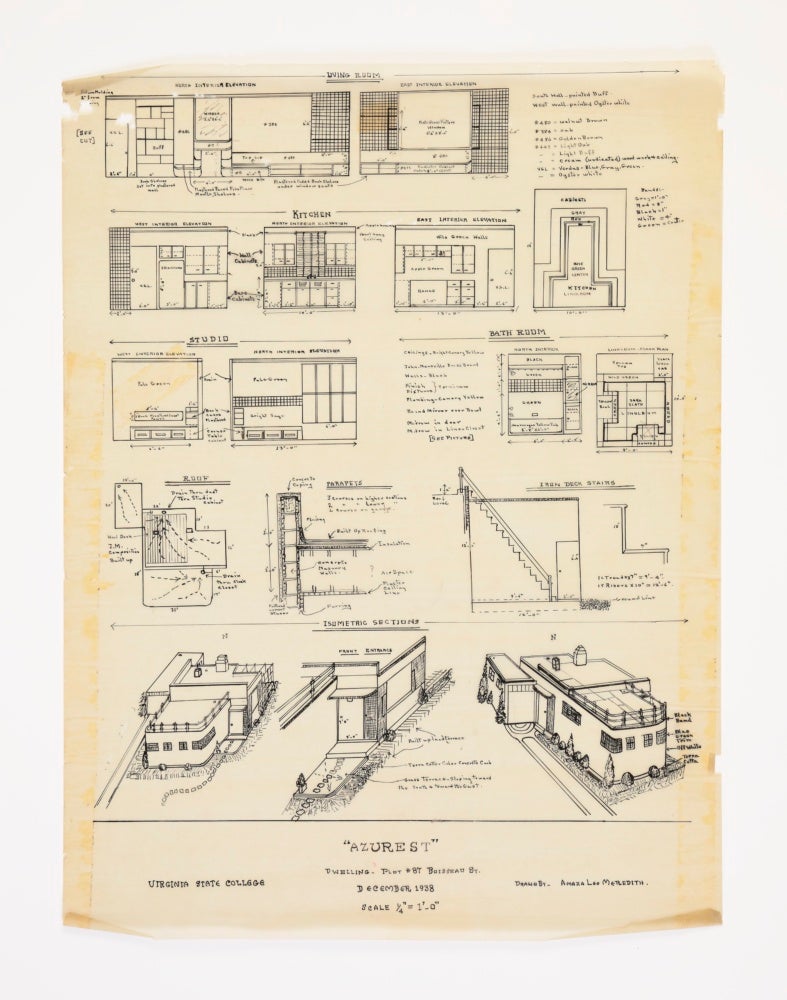

Meredith drafted exhaustive plans for the home, noting vibrant paint and tile colors like “apple green” and “bright sage,” and mapping a comprehensive drain system for its flat roof, open floor plan, and commensurate bedrooms for each woman. Meredith, not permitted to train formally as an architect, was nevertheless a zealous student of design. Her introduction of International architecture to Virginia State’s campus subverted both the dominant stylistic trends in the region and the strict masculinist codes of modernist architecture—marked by its promise of futurity in spite of women’s by and large exclusion from participating in shaping the world’s developing landscape.6 Meredith’s innovation amalgamated her formal education as an arts student and visits to significant exhibitions on modernist architecture in New York.7 She had learned draftsmanship from her father, Samuel Meredith, a white man who worked as a carpenter in her hometown, Lynchburg, Virginia, where their interracial family faced intense scrutiny. The relationship between Samuel and Emma Kenney, Amaza Lee’s Black mother, was illegal, forcing them to live separately for years until they were able to marry out of state. In 1915 Samuel committed suicide after years of financial stress, likely bolstered by the impact of social alienation on his job prospects.

Amaza Lee Meredith’s fraught family history made her pursuit of a relationship with Colson all the more daring in the face of severe cultural intolerance, as she was intimately aware of its consequences. Their home was a reprieve, and Meredith treasured it as such. She left behind fastidious records, including a scrapbook depicting Azurest South and their life in it. Its interior was meticulous, fashioned after the most modern trends in interior design. Meredith had taken inspiration from popular home magazines and department stores, turning an eye toward color and shape. She photographed it artfully, taking care to depict sunlight streaming in through windowpanes and art objects decorating the mantel. Her images illustrate the space and its emotionality, including annotations in her own hand: “A seat before the fire,” “Window seat/Rest & Peace.” Of the exterior: “A silence deep and white.” There are also photographs of Colson, of a guest on the sundeck, and implications of other social occasions: “A lawn party,” “Refreshments.”

Sweetness drips off the pages, a relic of queer intimacy told in private.

What especially stands out amidst her archive is a photograph marked “My Lady’s Boudoir.” The room, originally intended as a studio for Meredith but converted into a den for Colson, is shown as decorated with satiny fabrics and artwork of a female nude designed by Meredith’s student Cecilia C. Scott.8 The room and image are imbued with a manifestly sensuous energy. Meredith’s choice to entitle it a boudoir is a marked affirmation of femininity in a space shared by two lovers. Not only was home a private reprieve for the paramours, the dedicated educators opened their doors to students, faculty, family, and friends. In the book Amaza Lee Meredith Images Herself Modern (2023), architectural scholar Jacqueline Taylor explains that the couple hosted women’s groups for their church, while students utilized it as a space to study.9 Archival images show a home economics class taking place in Azurest South in 1939, the very year it was erected.10 In spite of its illegality, their relationship status was known to most of their loved ones and colleagues on campus and at church, and Meredith and Colson welcomed their community into Azurest South.11 In May 1939 Meredith’s sister Maude Terry wrote to the couple: “Dear Girls, So happy that you are ‘safe,’ happy and really beginning to live . . . we are rejoicing in your success and aims . . . I know you are having a wonderful experience with your homemaking. May you get many wonderful thrills from it all!”12

The relationship between Meredith and her sister Maude was one dear to both of them, as evidenced by their affectionate letters. Just after Meredith and Colson broke ground on Azurest South, Terry embarked on her own innovative endeavor in New York. She began securing undeveloped plots on the east end of Long Island, crafting a plan to circumvent discriminatory real estate practices that had kept the area inaccessible to Black buyers. It was here that the name “Azurest” was born. Terry’s poetic rumination on its sandy shores—“This place became ‘Heavenly Peace, Blue Rest, Blue Haven, Azure Rest,’”—inspired the name used to christen this unique locale. Meredith would adopt the moniker in naming her and Colson’s home down South as a tribute to the resort town where she would commune with her cherished sister, neighbors, and lover.13

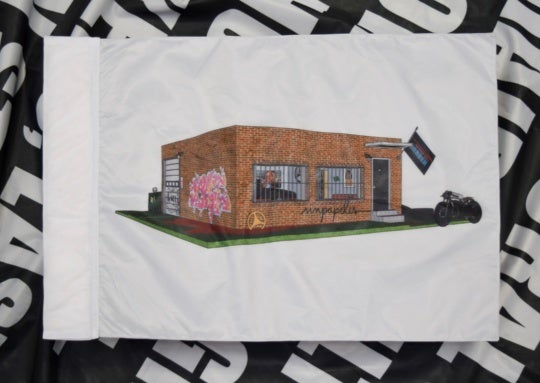

Meredith quickly got to work on designing residences for the beachfront haven. She first designed Terry Cottage for Maude Terry and her family, which included a room for herself and Colson. It was complete with a small drafting table where she likely produced some of the blueprints she dreamed up for other domiciles in the neighborhood. While most of the houses were never constructed, the avant-garde modernist style she introduced to Virginia was reiterated in her Sag Harbor designs; her imagined beach cottages employed asymmetry and geometric exteriors.14 As more homes cropped up near the shore, they were designed similarly, with minimalism and modesty in mind, likely inspired by Meredith’s first constructions. Blocks away, outside of the small, historically Black syndicate that Terry had created, the majority of Sag Harbor architecture is quaint and traditional, in Federal and Queen Anne styles.15 But Meredith’s dynamic modernist influence in Azurest is everywhere.

My paternal family members were among some of the neighborhood’s early residents. The historically Black community, now part of the New York State Register of Historic Places, was integral to my upbringing and sense of identity. It was there I found community among other young Black children, my summertime neighbors, during a period of adolescence in which I otherwise felt deeply isolated. In Azurest was my first example of the shield a home could provide, that a community could offer. As I aged, it became the place where I brought newfound friends, who marveled at the sight of a beach populated by mostly Black crowds despite the Hamptons’ reputation. In learning about Meredith and her role in developing the syndicate, my relationship to it wildly transformed; I envisioned her life there, creating and sharing space with her family and lover. In the shadow of Meredith’s legacy, Azurest became the place where I solidified my own queer relationship, endearing me more deeply to the woman whose legacy had entranced me. It felt as though Meredith had paved a path forward, forging new ways to feel at home.

She and Colson traveled between their northern and southern townships for the rest of their lives together. The two remained heavily involved in their professorial pursuits and campus life, innovating the possibilities for education on the campus of their HBCU.16 Upon her death in 1984, Meredith endowed her half of Azurest South to the university with the intention that it would become the “Alumni House,” fulfilling a goal of hers to secure space for students and faculty to convene, even in her absence. Azurest South was an opportunity for Meredith to innovate, an opportunity to connect with her community, and a material affirmation of her affections for Colson. Her deviation from expectations in the space of architecture, of art, of education, can be understood through the lens of a unique subjectivity informed by her Black queer identity. She was fearless in her subversions, transferring aesthetic sensibilities between regions and genres to build a life for herself and her partner, as well as transforming education in her Southern home state, introducing newfound access to arts curricula. The story of Meredith’s identity and history evaded me for years. In spite of annual visits to Azurest, I came to know about Meredith for the first time as an adult. It felt fated; she enthralled me. Exploring her legacy has made me ruminate on the possibility and expansive parameters of dedication, of family, of romance, of design, of home. It has enforced my affection for her and strengthened the invisible strings I feel between myself and this woman, whose legacy offers a roadmap for Black, queer artistry.

* These archival images shared in this theme feature were generously provided by the ICA at VCU. Dear Mazie, a group exhibition inspired by the life and work of Amaza Lee Meredith is currently on view at ICA at VCU through March 9, 2025, as curated by ICA VCU curator Amber Esseiva.

[1] See Keshav Anand, “How a Nude Le Corbusier Vandalised Eileen Gray’s Modernist Icon,” Something Curated, March 23, 2020, https://somethingcurated.com/2020/03/23/how-a-nude-le-corbusier-vandalised-eileen-grays-modernist-icon/. Gray disagreed with Le Corbusier’s assessment of the home, insisting upon the importance of intimate relationships in considering architecture’s purpose and saying, “A house is not a machine to live in. It is the shell of man, his extension, his release, his spiritual emanation.” Gray is quoted in Irene Sofia Comi, “Eileen Gray,”domus, March 24, 2024, https://www.domusweb.it/en/biographies/2023/03/24/eileen-gray.html.

[2] Virginia Normal and Industrial Institute was founded in 1882. Its name was changed to Virginia State College for Negroes in 1930, and finally Virginia State University in 1979. See “History of VSU,” Virginia State University. https://www.vsu.edu/about/history/.

[3] Meredith received a BA in art studio and art appreciation in 1930 and an MS in art education in 1935. Colson received a BS in 1923, an MA in 1924, and a Ph.D. in 1940. See Jacqueline Taylor, “Amaza Lee Meredith,” Pioneering Women of American Architecture, https://pioneeringwomen.bwaf.org/amaza-lee-meredith/; and “A guide to the papers of the Colson-Hill Family Number 1965-13,” https://ead.lib.virginia.edu/vivaxtf/view?docId=vsu%2Fvipets00050.xml.

[4] Jacqueline Taylor, “Biography,” in Amaza Lee Meredith Imagines Herself Modern: Architecture and the Black American Middle Class (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2023), p. 79.

[5] Taylor, Amaza Lee Meredith Imagines Herself Modern, p. 19.

[6] “For Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier, two leaders of the radical avant-garde, architecture was an instrument for cultural transformation, the reconstruction and formation of a new society, liberation from nineteenth century bourgeois culture, and the renewed spirit of modernization. . . . Accordingly, for Mies van der Rohe architecture was the materialization of the conscious and deliberate transformation of society expressed through the process of the physical construction of the state as manifested in building. Hence, the liberative promise of the modern project was a generalized, free (namely, patriarchal) collective production.” See Mario Gooden, “Architecture Liberation Theology,” in Dark Space: Architecture, Representation, Black Identity (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2016), pp. 24–25.

[7] While studying art at Columbia University’s Teachers College, Meredith “visited the Museum of Modern Art’s Modern Architecture: International Exhibition of 1932 for which Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock had assembled images and models of the new European architecture,” which they dubbed the “International style.” This visit is credited as a significant influence on Meredith, as evidenced in her design for Azurest South. See Taylor, Amaza Lee Meredith Imagines Herself Modern, p. 222.

[8] “Azurest South,” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form (Petersburg, VA: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1993), https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/VLR_to_transfer/PDFNoms/020-5583_Azurest_South_1993_Final_NRHP_nomination.pdf.

[9] Taylor, Amaza Lee Meredith Imagines Herself Modern, pp. 221, 282.

[10] Nicholas Som, “The Colorful Past and Bright Future of Azurest South, Home of a Pioneering Black Architect,” National Trust for Historic Preservation, July 14, 2021, https://savingplaces.org/stories/the-colorful-past-and-bright-future-of-azurest-south-home-of-a-pioneering-black-architect.

[11] See Taylor, Amaza Lee Meredith Imagines Herself Modern, pp. 283–84; and “Queer History Research in Virginia,” Library of Virginia, https://lva-virginia.libguides.com/queer-history.

[12] Taylor, Amaza Lee Meredith Imagines Herself Modern, p. 41.

[13] The Sag Harbor community is often referred to as “Azurest North” by scholars.

[14] While Meredith drafted designs for a number of homes intended to be built in Azurest, the only definitively known completions were Terry Cottage and Edendot, for friends Dorothy C. “Dot” and James Edwin Spaulding. See Sarah Kautz and Andrea Hart, “The Visionary Women of Sag Harbor’s Historic Azurest Community,” Preservation Long Island, March 8, 2021, https://preservationlongisland.org/the-visionary-women-of-sag-harbors-historic-azurest-community/.

[15] “Cornices And Pilasters: Sag Harbor Architecture,” Sag Harbor Partnership, accessed July 19, 2024, https://www.sagharborpartnership.org/cornices-and-pilasters-sag-harbor-architecture.

[16] At Virginia State, Meredith organized student exhibitions and introduced new courses, like photography. See Taylor, Amaza Lee Meredith Imagines Herself Modern, pp. 199, 209.

[17] Colson’s half was purchased by the university from her estate after her death the following year. See Jacqueline Taylor, “Designing Progress: Race, Gender and Modernism in Early 20th-Century America” (thesis, Online Archive of University of Virginia Scholarship, 2014), pp. 272–73; and “Amaza Lee Meredith (1895–1984),” Virginia State University Alumni Association, https://www.vsuaaonline.com/azurest-south/amaza-lee-meredith-1895-1984.

This essay is a feature release of Burnaway’s 2024 theme series Knock Knock.