There was never any symbolism or any real idea. I just went back to looking, which I guess is a theme that runs through my work. Looking at stuff and sort of regenerating something in me that keeps wanting to live.

Vija Celmins, in conversation with Robert Gober, 2002

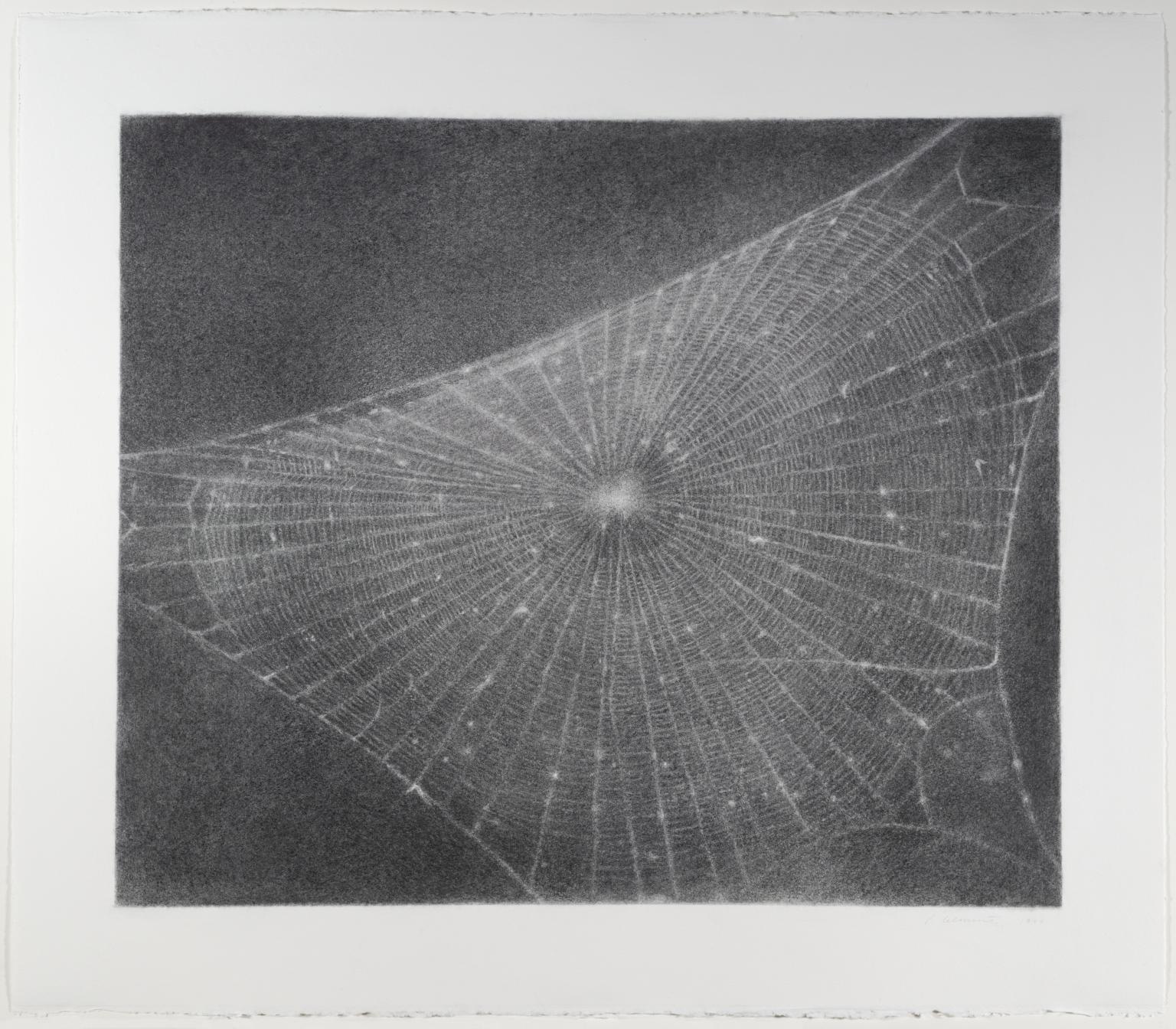

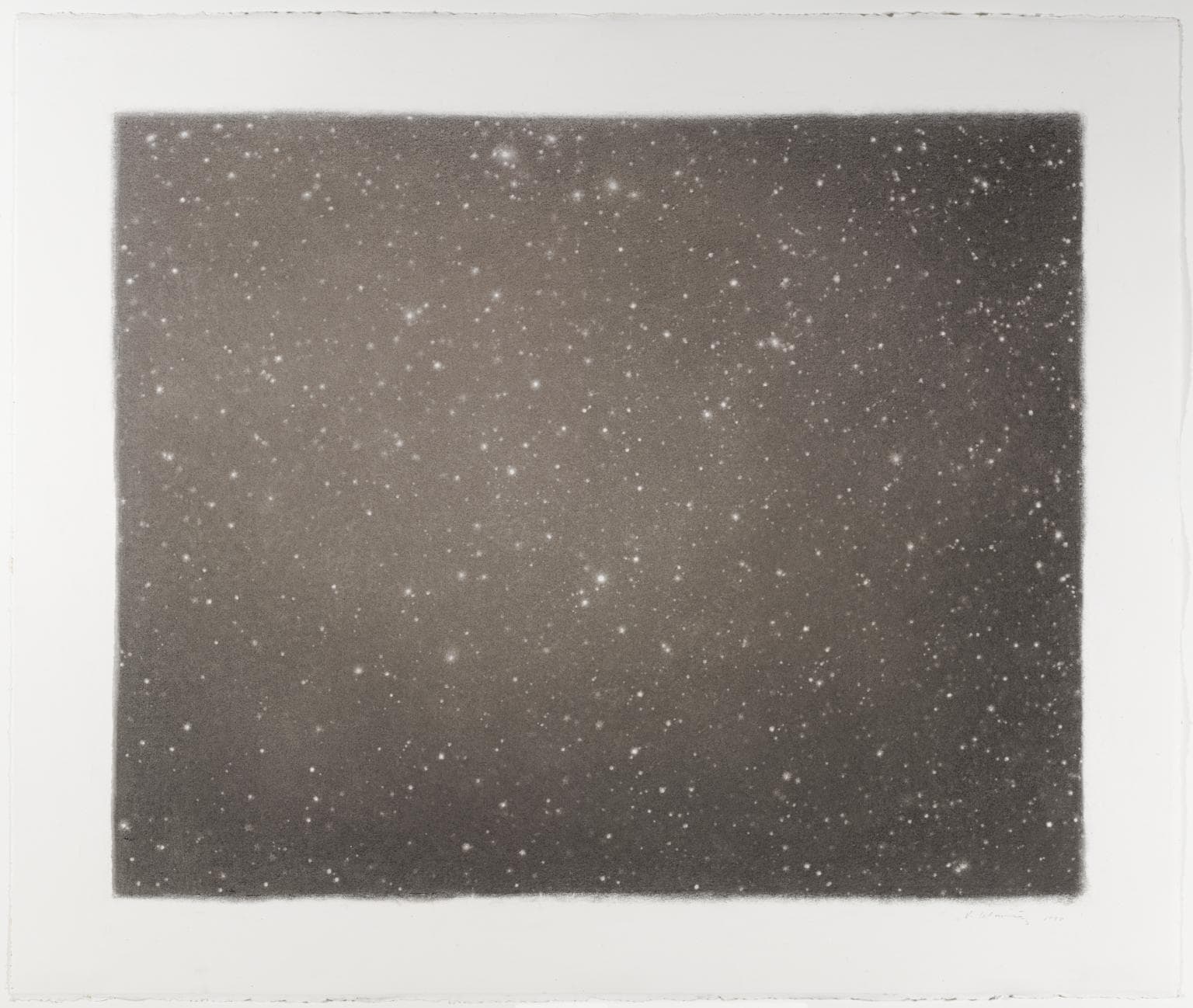

We may feel inclined to project onto Vija Celmins’s artwork — be it a meticulously drawn starscape, seascape, or webscape; or a series of desert rocks each presented alongside its precisely sculpted twin — a vision of artistic compulsiveness, of the artist’s possession by an eccentric technical commitment. Perhaps we perceive a struggle between Celmins and the rock that she would, with such exacting effort, attempt to reproduce in sculpture. And perhaps onto the later work we project an evolution of this struggle: Scrutinizing the many fields of sea surfaces, we may imagine that it is no longer such a fierce battle between them, but that the artist and the work have both achieved some semblance of comfort in their relationship, that they have grown together and that they have begun to grow a bit fond of one another. Looking to the charcoal spider webs, perhaps it seems that Celmins has finally warmed toward her subject — her subject: the spider web … the photograph of the spider web … the dialectical interplay of the photograph and the spider web … the armature which is this dialectical interplay … the formal intensities articulated across this armature — warmed such that where we once perceived austerity in the artist’s commitment, we now perceive contentedness, even luxuriation.

The viewer’s perception of Celmins’s procedure of meticulous reproduction provokes some projection of an exchange between artist and image — not only of the technical but also of the psychical or desirous terms of this exchange — a projection which is then relayed back to the painting, drawing, or sculpture and is felt to inhabit or haunt it. Celmins’s is a delicate, vestigial pointillism, with each touch of the pencil point “like a point of consciousness,” she says, “like a record of having been there.” The image is an armature for an articulation of formal intensities, yes, but the image — and the represented object, which must, we feel, be related to desire in some way — nonetheless serves to delimit these intensities. The purely formal relation between the white speck among other white specks upon a layered field of black always remains indexed to a relation between star and space, yet again between the artist’s process and her desire.

A cascading of relations: first, the relation between the projection of a perceived method of composition, and second, a perception of the object of representation. Our projection may or may not be accurate, but whether the artist uses eraser or pencil to create the stars ultimately does not matter. What matters is that we imagine a meticulousness that has as its source a desire, a yearning so powerful to compel the artist to engage with such tedium time and again. Where do we look for this object of desire? Of course we look to the image, perhaps to what the image represents, but the answer cannot be found there: the image is merely the occasion for an articulation of formal intensities. So do not look to the waves, then, instead look to the relation between the drawn waves and photographed waves. Imagine it as a mnemonic relation, for the artist cannot look at the photograph and the drawing of the photograph at one and the same time: “When I was looking at the rock and painting the bronze, I had to remember what it is I saw even though it was only five inches away.” This entanglement of memory and desire — the poverty of human memory in relation to the wealth of human desire — is the primary subject of Celmins’s art.