The current survey of Barthélémy Toguo’s work at the SCAD MOA gives space for repetitious expansion and reflection. Toguo’s work is often oriented by his French-Cameroonian nationality, and this exhibition is additionally contextualized by our shared present moment of pandemic, genocide, and environmental degradation

Urban Requiem gives time and space for avenues of inquiry to congregate and tangle with one another. Repeating banana boxes on the floor and stamped messages on the gallery wall provide a sense of sacredness to the exhibition space. There is a universality to the objects, meaning that they could be installed almost anywhere with a similarly profound impact. Akin to Duchamp’s Air de Paris, Toguo asks us to question the illusion of difference which defines the borders of geography. During an interview for FIAC, an international fair of contemporary art, Toguo said that “the final form is the outcome of my discourse, so I have to use everything available to me.”

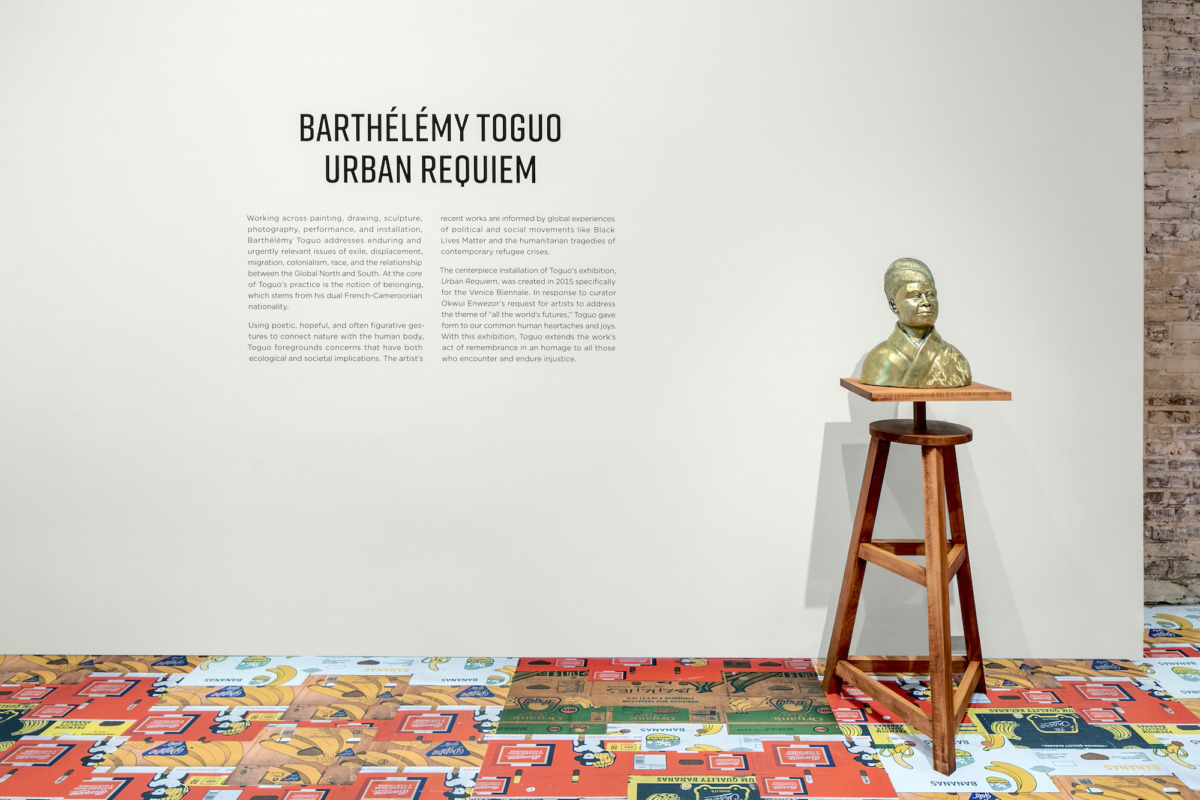

Urban Requiem is maximalist in medium and thematically interwoven. Portraits of individuals who were murdered by police officers (Black Lives Matter series) are situated in front of wooden revolvers (Don’t Shoot II), while light shimmers off a bust of civil rights leader Ida B. Wells-Barnett, who exposed the cruelty and terror of white lynch mobs in her investigative journalism. It is no coincidence that Toguo has commemorated Wells-Barnett in a dialogue protesting police brutality, as her work was seminal in documenting and contextualizing the violent deaths of hundreds of Black Southerners in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Tonal harmony plays out as well, with inadvertent connections to local dialogues, such as those led by Sistah Patt & Sistah Roz’s Underground Tours and the Pin Point Heritage Museum on white supremacy and the preservation of Black history, particularly that of the Gullah/Geechee people. While viewing Urban Requiem, I remembered Sistah Patt’s multifaceted effort to urge the City of Savannah to recognize that ballast stones, which were first used in the ships that brought enslaved Africans to the city and later operated as street pavers, were being stolen daily from beneath security cameras. Toguo, like Sistah Patt, reminds us that historical and spiritual ramifications exist materially.

The stamps of Toguo’s titular piece Urban Requiem were originally made for an installation at the Venice Biennale in 2015, organized by Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor. The stamps rest on several steel pyramidal stands, like giant mushrooms. After a first-glance, the stamps shift to an almost uncanny figuration, as if they have been worn down and smoothed by the hands of giants. With mythic proportions, these objects speak to the magnitude of human impact on each other and on nonhuman life. Toguo reminds us with this work that humans are creatures of disturbance — nurturing, stacking, tilling, killing. These stamps also convey the ways in which the scale of our hubris can lead to the overlooking of our relations with each other. Stamping is a common art class exercise in elementary schools and daycares but it is also a mundane act of the state via passports, visas, and postage. To be stamped or to stamp is to label, categorize, and surveil. Stamped phrases such as “LIVES STOLEN”, “HOPE”, and “TIBET” politically dissolve the line between printmaking, propaganda, and capitalist commodification. Towards the bottom corner of each print, a thumbprint acknowledges the human printer, calling to mind the imperialistic optimization of thumb-printing. In a 1980 essay, Carlo Ginzburg locates the institutionalizing of the fingerprint.[1] While Toguo does not explicitly address this imperial past, the inclusion of various printmaking techniques together serves as a type of unified reclamation. These wall hanging prints, with simple black ink, serve as signposts to protest chants of the past and present.

A site-specific piece, The Disasters of War, carries the eye through red ink coming from the wrists of an outstretched, gasping figure in a life-size drawing. At abstract expressionist scale, this ink work imposes a temporal reverence. While a wailing figure has a nail-like object piercing their left hand, harkening to the crucifixion, the flowing lines with a wet finish reminds me of the Lakota protest charge “Mní wičhóni” (“Water is life”) heard at Standing Rock. Savannah is a city of and by the water, and it is likely that Toguo mixed water from the local tap with his ink to create this work.

The same red ink flows like whispers of blood or spilt wine into other works, such as the postcards exhibited in a grid-like fashion. These works are part of Toguo’s Head Above Water series, and the cards are addressed to the artist from various places in Mexico and Nigeria, with brief messages about life, current events, and aspirations. Toguo’s choice of self-address speaks to the extractive explorations and limitations of Alan Lomax in the American South. I’m also reminded of the affirming documentary work of Agnes Varda, particularly her 1975 Daguerréotypes.

Toguo incorporated Savannah into this practice of documentation by leading a postcard making workshop for teens at SCAD that centered around themes of belonging and exile. This connected workshop speaks to how representation in the archive can affirm life and educate future generations. Urban Requiem localizes, personalizes, and critiques broad cultural themes while Toguo also addresses mechanisms of remembrance, using similar methods aligned with theorist Ariella Azoulay, who states in Potential History that archives, “[are] predicated on the destruction of existing worlds.”[2] While requiems are masses for the dead, Urban Requiem purports that destruction is not eclipsing. In tidelands, the passage of time, of life and death, is a continuum. Toguo’s Urban Requiem rouses an already spiritually charged place to address the frayed edges of our collective soul.

[1] “In 1860 Sir William Herschel, District Commissioner of Hooghly in Bengal, came across this usage, common among local people, saw its usefulness, and thought to profit by it to improve the functioning of the British administration.” From Carlo Ginzburg and Anna Davin, “Morelli, Freud and Sherlock Holmes: Clues and Scientific Method,” History Workshop 9 (1980): 5–36.

[2] Ariella Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (New York: Verso, 2019), 174.