“Get on the ground! Roll over, Mardi Gras!”

I stood in a clearing with a hundred others. On an outdoor stage, a man dressed in vermillion long johns and a Napoleonic hat projected broken Franco-English through a microphone. This dialect—both foreign and familiar—waltzed between my ears as I mentally approximated the vernacular Cajun French of my childhood into English. Draped in patterns, costumed in flowers, a caravan of revelers yawned and stretched while bringing hip flasks of liquor to their lips. It was 7 a.m. in rural South Louisiana. Costumed and curious, I stood with other first-time runners of the initiation ceremony, listening as the speaker prepared the procession’s commencement. Our tall, conical hats pierced the morning fog.

Every year, on the day before Ash Wednesday, a prairie speckled with farmlands and familial cemeteries three hours west of New Orleans becomes the backdrop for an anachronistic, vernacular tradition. The Cajun and Creole folk bacchanal known as Courir de Mardi Gras (“Fat Tuesday Run”) populates the landscape with figures in grotesque, carnivalesque, handmade costumes.

A few weeks before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, I traveled to my hometown of Lafayette, Louisiana, to experience the Courir for myself. Rural towns across the Acadiana region celebrate their own versions of the event, with some more traditional than others. I chose to attend a younger sister of the Courir tradition on the outskirts of Eunice, Louisiana: Faquetigue Courir de Mardi Gras.

Standing in the dense assembly, I fidgeted with my mask while waiting for further instructions. The night before I had called my partner and expressed my nervousness and apprehension. Visiting my hometown always puts me slightly on edge as it stirs up unresolved tensions, particularly the ones I felt as a child while grappling with my queerness. My partner reminded me of my original intention: to participate in a tradition of my ancestors while keeping the observant distance and perspective of an anthropologist. I would be operating much as I always have in my hometown: as both an insider and an outsider.

Cajuns have historically been outsiders in the American South: culturally distinct and proud to portray their otherness through traditions such as Courir. They are descendants of Acadians (the word “Cajun” a corruption of “Acadian”), themselves descended from seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French settlers of the Canadian Maritime provinces and the region’s Indigenous peoples, specifically the Mi’kmaq. The forced removal of the Acadians from Nova Scotia by Great Britain in the mid-eighteenth century divided families and exiled them to decades of displacement and nomadic roaming. Most port cities rejected their entrance; their arrival in New Orleans led them further west to a region known as Attakapas, later called Acadiana.

Mostly seen as an alien, lower-class ethnic group, the Acadians remained removed from mainstream cultural assimilation until the 1920s. Their provincial isolation met its end with government mandates that schools teach English exclusively. With rural Cajun French as their only tongue, children were shamed and reprimanded for speaking their vernacular dialect. The cultural world of Acadiana, its folk practices, and its language gradually became closeted in response to the typical pressures of Americanization. The “irregularities” of Acadian customs were displaced, though never completely forgotten. It wasn’t until the sociopolitical movements of the 1970s that regional advocates were inspired to embrace cultural preservation and resilience. This cultural revival marked the decade as the Cajun Renaissance, a period of resurgence in Acadian traditions and customs. Courir, or “the run”—a mutation of medieval French Catholic traditions, specifically a fête known as the “Feast of Begging”—became a social institution, reenacted annually to uphold these cultural legacies.

The rules of the Courir are simple. There are no observers or tourists, only participants. There are no beads. The “run” refers to the chasing of a chicken, and runners must remain full costume with their faces covered the entire time. It feels strange, months later, to reflect on a mask requirement for a bacchanal only days before the onset of a global pandemic. Mentions of the virus were relatively infrequent then, with few infections nationwide at the time. I recall revelers jubilantly toasting Mexican bottled lager and exclaiming, “Fuck Corona!” unbothered by a threat they couldn’t foresee. Joviality was contagious in the reckless spectacle.

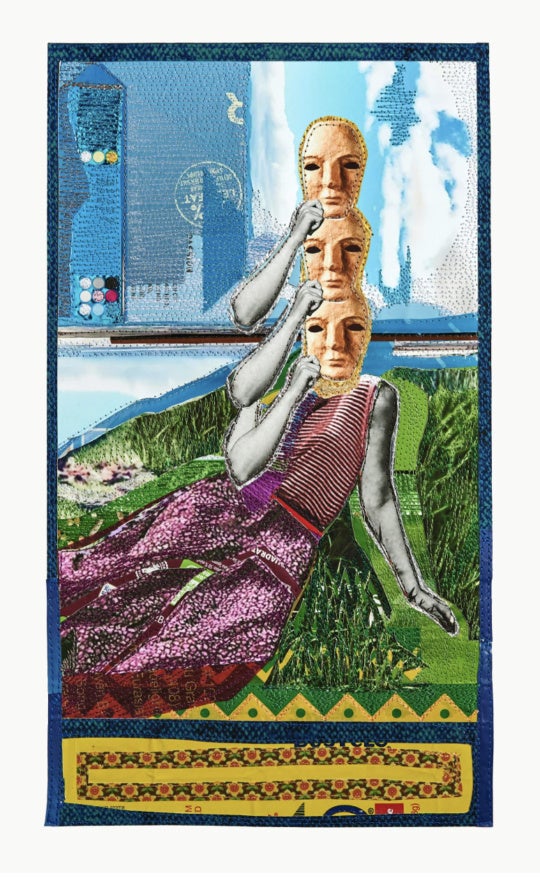

Mardi Gras succeeds when social structures have been reversed. Men and women appear in drag, the old become young, the poor parody the rich. In Courir, the runner embodies a kind of third space—one based in liminality, transformed by costuming, and masked in anonymity. The mask allows the wearer to shed inhibition, providing an outer cocoon for inner transformation. Binaries become altered, modified, and collapsed. Lacking urban polish and bedazzled props, Courir calls upon rugged resourcefulness while upholding medieval fascinations with the grotesque. Masks have eyes made of buttons and noses made of stuffed stockings that pop out from the face, while the body is disfigured and re-proportioned through ragged scraps. Youthful boys appear as haggard nuns. Costumes enable both anonymity and parody: conical hats called capuchons mock noblewomen, mortarboards poke fun at scholars, and miters make fun of the clergy.

The figures of Le Capitaine and Le Depute ruled over this melee. Silently processing on horseback, wearing a purple cap, and bearing a white flag, Le Capitaine upheld an illusion of order amid the chaos. The man who had spoken onstage earlier was soon revealed as Le Depute, a more theatrical version of his stoic counterpart. Le Depute explained to the crowd what the day would entail: we would traverse across prairieland, parading from one rural house to another. Le Capitaine, the intermediary between the costumed merrymakers and the surrounding community, would approach each home first and calmly ask its tenants if they were willing to bear witness to the performance of Le Mardi Gras. If the residents agreed, he would raise his white flag, signaling us runners to surround the home and perform a begging ritual consisting of groveling, dancing, and singing in Cajun French. If satisfied by our collective performance, the homeowners would give us pennies and ingredients for a communal gumbo to be prepared later in the evening.

Encircling the crowd, a band of women wielded burlap whips and bourbon was introduced as La Force. Their male counterparts, Les Villains, stood even further outside of the circle, each wearing black and red vestments emblazoned with a scarlet rooster. A horn sounded and these enforcers moved in, issuing orders of buffoonery and referring to all of us as “Mardi Gras” in the Cajun tradition. “Get on the ground! Roll over, Mardi Gras!” they exclaimed. After this initiation, we collectively stood up to receive a baptism by bourbon. “Drink, Mardi Gras!” I gulped down a warm mouthful before the crowd pushed me toward the ensuing madness of the day.

We funneled into a caravan of devilish tricksters as the spring sky opened, revealing a long, narrow dirt road lined with pickup trucks. In contrast to the better-known, urban Mardi Gras parades in New Orleans, Courir traverses across the rural landscape. How surreal to witness these vaudevillian Stations of the Cross! The farmlands became the backdrop for us exiled and banished misfits to taunt, steal, dance, and chase.

When we arrived at the first of many prairie homes, Le Capitaine approached its residents, a family crowded on the front porch. Small children peered from behind their mother’s thighs, gawking frightfully at the bizarre scene. When the white flag hit the sky, we stampeded across the yard, our debauched dance intensifying as the group groveled for ingredients. Cracking their whips, La Force commanded us all to dance “for the Mardi Gras!” With open palms, we lunged forward on our knees in hopes of receiving small tokens of recognition.

Suddenly, the matriarch on the porch retrieved a terrified chicken from a cage. She threw the chicken into the air, and it squawked frantically above us as the crowd attempted to follow its arc. A chase ensued as the spastic bird fluttered about until it was caught by a boy disguised as a werewolf. The fiddlers accompanying our parade picked up right where they had left off when approaching the house, and the crowd delightfully cheered, propelling ourselves onward toward the next home. As we traveled on, I struck up a conversation with a reveler dressed in red and blue. I soon learned that when he wasn’t chasing chickens, he was a young Catholic priest. Guzzling down the contents of a nondescript flask, he mentioned that he had to conduct morning mass the next day.

Off in the distance, runners standing on the backs of horses approached a twenty-five-foot greased pole topped with a caged chicken. Fringed bodies gathered at the base of the pole and began to mass atop one another—attempting to reach the chicken, repeatedly failing, and sliding down the oily stake. An adolescent boy eagerly scurried to the top of the heap and reached for the cage but fell short. He fell to the base of the pole empty-handed and dazed by the tumult of his descent, and the prize was obtained by another runner.

We departed from the field and approached a small rural cemetery that included the grave of legendary Cajun musician Dennis McGee. As we reverently crouched around his tomb, some musicians began to play one of McGee’s melodies.

As a child, I was fascinated with gods, myths, and the supernatural—all of which provided me with symbolic entry points to the mysteries of the world. Now, as an artist, I often attempt to recode or hack these myths, to repopulate their stories with figures and symbols whose hidden meanings are my own. Courir is powerful precisely because it plays with notions buried in the collective unconscious: its characters, stories, and poetic substance form a latent secret knowledge.

Le Depute stood to address us. “We’re all brought to the Mardi Gras to have fun and joke around. But after this, think of that begging ritual, being on your knees, with palms out, asking for help. Think of the shame that it symbolizes. Most importantly, think of your neighbor or a stranger in need, with their hand held out, and think of what they must be feeling. Extend a hand to that person, because we’ve all needed help at one point or another.” The music swelled in the afternoon air, filling the graveyard with ghostly chords and French lyrics of longing. I grew up with this music, but I felt possessed by the song in a way that I hadn’t before.

[1] Ancelet, B. and Edmunds, J., 1989. “Capitaine, Voyage Ton Flag”. Lafayette, La.: Center for Louisiana Studies, University of Southwestern Louisiana.

[2] Bernard, S., 2003. The Cajuns. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi

This essay is part of Burnaway’s yearlong series on Exurbs and the Rural.

It originally appeared in Laws of Salvage: The 2020 Burnaway Reader.