Life—at least in my experience—weaves itself in a comical, cyclical way.

I wrote this line a year ago after attending School of the Alternative (SotA), an unconventional art school / residency / summer camp. According to the mission statement, SotA is “a learning space that is equitable and caring and radical in response to a world that is not.”1 Every May, artists learn, work, and live in Black Mountain, North Carolina, on the historic first site of Black Mountain College (BMC). Faculty, staff, and students cohabitate in one lodge, and all help sustain the temporary community through work and service. Instead of a traditional classroom environment, the school applies a collectively built and self-directed approach to learning. This means faculty and staff attend classes, and students also teach pop-up classes. When I attended in 2023, the youngest students were nineteen, the oldest in their late sixties. I know it as a haven for misfits and queer people in the Blue Ridge Mountains.

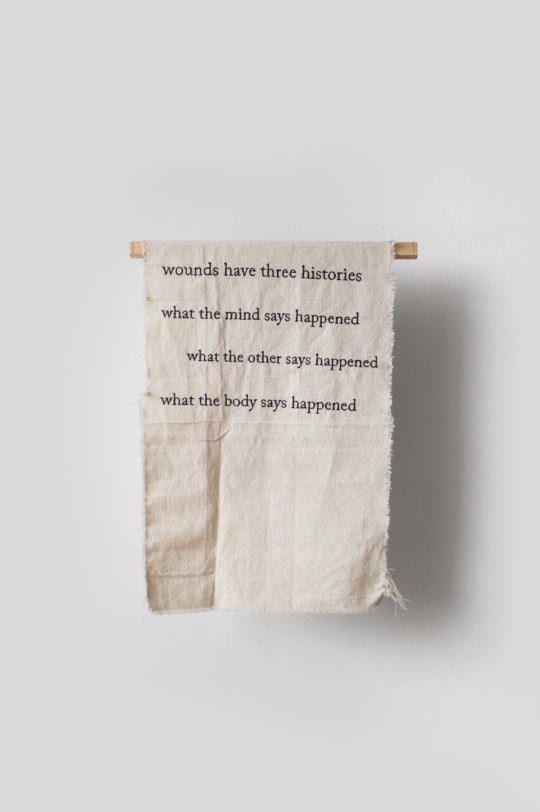

I returned in 2024 as a student once again and as a teaching faculty member. I knew the moment I left my first encounter with SotA that I needed to come back. It felt like a vibrational pull to a fleeting period of time where I could abandon my own expectations: of myself, of what I must do with my time, of how I show up in the world. When I left SotA both times, I left in a dream state. I can only recall vignettes of my time spent on that YMCA campus and Weatherford Hall. The experience is all-consuming and addictive with bouts of pink-tinted romanticism; it’s like a crush.

I remember the angry tears I shed when I feared my pretreated cyanotype fabric was mistaken for YMCA bedsheets. I also remember being comforted by fellow participants. I remember the cold midnight air on my skin that surrounded those of us who laid our bodies down and faced up towards the sky, screaming as we saw the geomagnetic storms that caused the aurora borealis to make a surprise appearance in the North Carolina mountains. Yet, I can’t remember the fruitful conversations I had in the art room at 2AM with fellow insomniacs. I can’t quite remember the meals I tasted from the communally run kitchen during the two weeks I was there.

As I begin to unpack the box of supplies and personal artifacts from this past year, I find myself encountering a form of psychometry. SotA has been my only in-person residency, and it feels like a sacred first relationship that I maintain in devotion to its infectious power through my returns, my communication with residents after the sessions end, my homage to it in written recollection, and my own teaching artist work in nontraditional educational spaces.

Black Mountain College

BMC began in 1933 by John Andrew Rice—a former Rollins College professor from South Carolina who was dismissed from the Florida university for his unorthodox way of teaching and misalignment with the school’s ideals.2 Rice’s return to the Carolinas emerged out of his desire to prioritize experiential learning, artistic expression, and democratic governing among its teachers and students. Just prior to BMC’s official start year of 1933, the Nazi regime in Germany forced the Bauhaus to close. Josef Albers, a former Bauhaus educator, was invited personally to head the art program at BMC, leading his wife Annie Albers and other Bauhaus-affiliated members to relocate to the American South in search of a new future for their teaching visions.3 Across the twenty-four years it took place, initially on the YMCA Blue Ridge Assembly for the first four years and then Lake Eden for the remainder of the school’s tenure, those who attended shaped the arts education and pedagogy into one that was reflective of the attendees’ souls: revolutionary in creative thought and a willingness to experiment with teaching.

While BMC is often still spoken about as if it was a paradise, it’s vital to contextualize the time in which the school began and who it really served. Research reveals the progressive actions taken by BMC were far ahead of the timeline in terms of how the rest of the world viewed social justice, but it was still founded by a white male body of scholars and supported a primarily white student body. Recruited based on vocal testimony of her teaching work at Spelman College in Atlanta, Alma Stone Williams was the first Black student at BMC’s Summer Music Institute of 1944. The decision to integrate in a time of segregation was met with resistance—as evidenced by the departure of a student and the college’s assistant treasurer upon the announcement of Williams’ arrival.4 It is an unshakeable truth that is reflective of that rose-tinted lens I mentioned earlier in regards to crushing: Racism and sexism in the wider world could still be found at BMC. Things were not as ideal as they seemed.

School of the Alternative

Birthed out of the visions of the artist couple Chelsea Ragan and Adam Void—who are originally from South Carolina and Georgia but both moved to western North Carolina after being in New York City—SotA was originally founded as the Black Mountain School in 2015. Its founding was borne out of a convening of eighteen colleagues on the Lake Eden campus that cemented a two-person idea into an actualized collective framework.5 While the Black Mountain School “positioned itself with its predecessor,” a cease-and-desist letter by the well-funded state university program that now holds the rights to BMC forced the school to change its name to School of the Alternative in late 2016.6 Declaring in this shift that they were “better focused on the fight for alternative education,” SotA resides at the mirrored nexus of BMC in creating an independent reinvention of traditional arts education.

SotA features a multitiered curriculum, the inspiration for which was three of the four states of matter found in nature. “Solid” classes are built on sequential learning, “Liquids” function as stand-alone workshops, and “Gas” classes are ephemeral in nature.7 Through an application process, faculty are selected to lead solids and liquids within set dates and times, while gas classes take place anytime outside scheduled class time. In essence: You choose from across the three categories of classes and can determine how much each structure your days and nights. At SotA, students and teachers are intended to be equal. Any resident is eligible to present their particular gifts, skills, and knowledge to the cohort at any point throughout the session.

The final night of the annual residency is called Activate the Space, during which ideas are never too big or wacky to be executed. The program was inspired by the Happenings of Allen Kaprow and John Cage at BMC in the 1950s, and I believe more and more that SotA picks from the creative heights of BMC’s history and adapts them into contemporary quirks. Everything from Big Bed—a dorm room filled with mattresses that cover every inch of the floor to create a big bed—to an 11:11 basement haunt that could only be entered when the clock struck that time or a prom that turns into a silent disco had woven itself into the emotional high of the residency’s end. These finales left me with so many tears and contagious laughter as I realized that I would soon leave this brevity of freeness and radical living, that I ended up staying up all night to relish in those finite conversations and moments.

For an artist who never attended summer camp growing up, it’s the closest thing I can call and return to as an adult trying to navigate the weight and pain of this world.

I recently reread diary entries I had written while at SotA. They are all found in a journal that was gifted by a fellow resident, Jameo, who has stayed in touch across the bicoastal distance and time difference between Miami and Los Angeles. As much as I try to summon the immediacy of what I experienced, these text memories are my best grasp at the feelings and sensations of being there, especially the sleep delirium and body highs I experience from being around affirming presences that reminded me of the vitality of being “too much.”

There’s a tenderness to the all-nighter spent in your bed, to the budding sweetness that begins with threading string in an art room and then flowers into creature comforts I can’t and don’t want to leave. So I stay up and tell you my troubles. I ask you to prom because why the fuck not? I guess I’ve missed crushing on humans and the rush of adrenaline I feel for when you listen and make me feel held.

In coming back to the same place in the cycle of an entire season, I miss the souls that are absent and am grateful for fresh faces. It is full circle but not complete, as those who comforted me a year ago are not here to comfort me today. I allow myself to feel grounded on this earth, instead, laying my head down to rest on the grassy hill that has not moved since the last time I was here.

In resonance, I felt a heart in my gut, at the bottom of my stomach, it was big and red and juicy. It felt like it was ready to explode, but maybe it was just pumping blood by routine. In dissonance, I feel it at the bottom of my feet. I feel like when I hear this kind of music that clashes and crashes, I wanna move my feet as they itch to be rubbed against the ground.

The Spirit of Intimacy, This Appalachian Land, and These People

I found ritual practice in the fellow residents I’d meet at SotA and their personal offerings to our time together in Appalachia. I found ritual practice in the rocking chairs found on the porches of Eureka Hall, where I stared out at the peaks of the Seven Sisters as I witnessed Solid and Liquid classes play out in the distance. I found ritual practice in the common ground of collective care created by complete strangers and familiar faces, of holding space for those that were processing the grief tied to the loss of loved ones, pets, and broken relationships. I found ritual practice in dismantling individual hierarchy.

These memories are now framed and altered by the active aftermath of Hurricane Helene on the towns of western North Carolina, ongoing as I write this. I witnessed remotely how flooding ruined the homes and work studios of my SotA community, destroyed their gardens and safe spaces, and sent them to live elsewhere in order to drink clean water, as recuperating became too much to deal with as life moves on. Images of mudslide destruction on the YMCA campus punched me in the gut, as questions of what’s to come for SotA’s future sessions crept into my thoughts. It is a looming unknown that remains unanswered but countered by the clarity I feel that the stewards who sustain SotA can keep it nourished.

On the cusp of its tenth year, I struggle to contextualize SotA even after attending twice in back-to-back years. It’s not quite a residency in the traditional art-making sense but it’s also not quite an art camp in the rigorous sense. What I do know is that it is a space to resist performative acts of care and false promises, where genuine interest and excitement for the arts is accepted as the emotional baseline. Queerness and transness are intrinsic identities that uphold the ecosystem, seen in the top surgery fundraisers posted on the community board and the callouts to partners vocalized live on the residency radio station. A Palestinian flag greets you as you enter Weatherford Hall and a grief altar with a tarot deck is left for anyone to pull from. For an artist who never attended summer camp growing up, it’s the closest thing I can call and return to as an adult trying to navigate the weight and pain of this world.

[1] “Our Mission,” School of the Alternative, accessed October 22, 2024, https://schoolofthealternative.com/mission.

[2] Jennifer M. Ritter, “Beyond Progressive Education: Why John Andrew Rice Really Opened Black Mountain College,” Rollins Undergraduate Research Journal 5, no. 2 (Fall 2011): pp. 2–4. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1044&context=rurj.

[3] “Bauhaus to Black Mountain: Josef and Anni Albers,” North Carolina Museum of Art, accessed October 22, 2024, https://ncartmuseum.org/exhibition/bauhaus-to-black-mountain-josef-and-anni-albers/.

[4] Micah Wilford Wilkins, “Social Justice at BMC Before the Civil Rights Age: Desegregation, Racial Inclusion, and Racial Equality at BMC,” Journal of Black Mountain College Studies 6: Progressive Education, Graphic Design + Women on Craft (June 2014). https://www.blackmountaincollege.org/6-17-micah-wilkins/.

[5] Isaac Kaplan, “At the Site of Black Mountain College, a New Residency Program Aims to Continue Its Legacy,” Artsy, June 6, 2016, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-black-mountain-school-is-building-on-the-foundations-of-its-predecessor.

[6] “Black Mountain School Changes Name to School of the Alternative,” School of the Alternative, accessed November 28, 2024, https://schoolofthealternative.com/namechange/.

[7] “Class Structure,” School of the Alternative, accessed October 22, 2024, https://schoolofthealternative.com/class-structure.

This essay is a feature release of Burnaway’s 2024 theme series Crush.