Nuveen Barwari and Beizar Aradini’s two-person exhibition Third Culture Kids at VERSA in Chattanooga reflects both artists’ experiences growing up in Nashville in largest Kurdish community in the United States. Some third culture kids grow up in a different culture from the one in which their parents were raised, and others grow up somewhere different from the the native land specified by their passports. In either case, such children are exposed to a broad array of cultural influences during their developmental years, resulting in an identity that combines two expressions into a distinct third culture.

Aradini is still based in Nashville, but Barwari recently moved to Knoxville, where she is pursuing an MFA at University of Tennessee. I chatted with both of the artists about Third Culture Kids and their experiences as Kurds in Nashville. Our conversation took place over the phone in September 2019 and has been edited for print.

Joe Nolan: Do you feel like the concept of “third culture” comes across to viewers whose families have been part of American culture for generations?

Nuveen Barwari: I think a lot of people can relate to it—that’s something we saw at the opening. For example, skateboarding has been an underground third culture of a kind. Some parents have never skateboarded, and they’re against it. One thing about a third culture is that it’s kind of like its own language. This whole project started with me and Beizar having a conversation about growing up here [in Nashville]. Language barriers are just one experience we’ve shared in common.

Beizar Aradini: There’s a continual shift between language and culture. I was always taught about the importance of not losing our native language. If we never lose our language, our Kurdish culture will always be alive.

JN: Nuveen, rugs are making regular appearances in your recent work, and there are a number of them in this show. In one work, you’ve added the word LIT to a vintage rug that using some shimmering gold fabric. It’s a fantastic clash of materials and patterns.

NB: When I cut those letters into the rug, I was like “This is a word my parents would never understand.” But some older Americans don’t know what that means either. It’s cultural, but it’s a generational thing too.

BA: With art, making becomes another language for us outside of Kurdish or English. We’ve both found ways to connect back to our parents through art.

JN: So language and generation gaps create barriers, but so do history and geography.

NB: I’ve been in Knoxville for like a month, and I feel myself doing this geography lesson before I can explain my work to my peers. We have extra explaining to do as first- or second-generation immigrants from the Kurdish diaspora. I’ve been a geography expert my whole life because this story is so complicated.

JN: Religious traditions are also a part of this story.

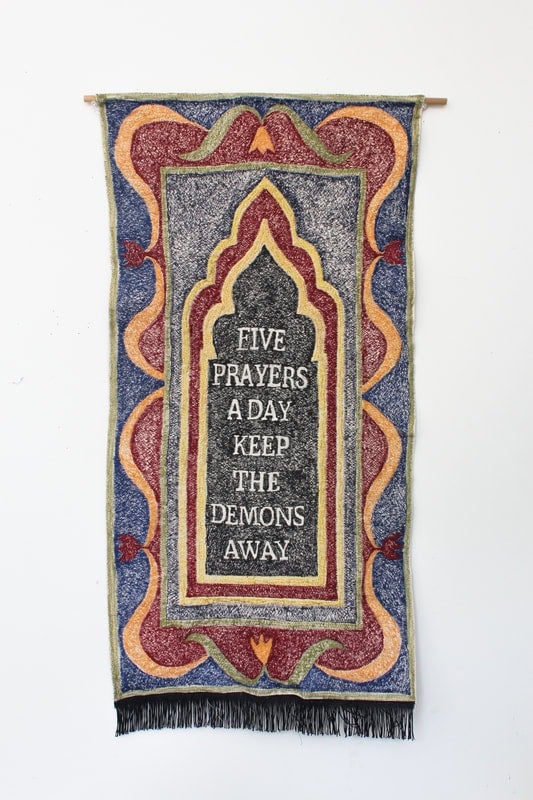

BA: Daily Routines is a tapestry that I sewed: it’s a prayer rug that says “Five prayers a day keep the demons away.” Of course I stole that phrase from the idiom “An apple a day keeps the doctor away.” It’s about bringing the two together. I grew up as a practicing Muslim, and I did my five prayers everyday with out questioning. I’m not practicing that now, but it’s still a big part of who I am today. When I was a kid I really felt that by praying I kept the bad things away—that’s the mentality that I had. Daily Routines is about bridging English language and American culture together with the things I was raised with and taught to believe.

NB: I was born in the US but lived in Kurdistan from sixth grade through eleventh grade. What’s funny is the one thing I would ask for from American visitors was Cheetos. You need to take a needle and poke tiny holes in the bags to get the air out of them and make room for other things in your luggage. In Red Hot Melting Pot, I’m cutting out these arches from traditional rugs and replacing them with Flamin’ Hot Cheetos bags, trying to merge the two cultures.

I’m heavily influenced by the way [Nashville artist] Marlos E’van uses food in his art. One thing I noticed at the opening was that people thought the Hot Cheetos were representing hell, and I was like “This is Kurdish-American art. This is not Islamic art. As Middle Eastern artists, we shouldn’t all be lumped into contemporary Islamic art.

JN: Third Culture Kids is arranged with each of your works alternating along the walls, but it’s not difficult to tell your work apart. For instance, all of Beizar’s embroidered pieces are clearly by the same artist.

BA: Those are the more sculptural pieces that hang down from the ceiling. This is an ongoing project I’ve been doing of embroidered photos of my family—the whole project is made of thread. When I’m working from family photos, it’s usually the first time I’ve seen these images. My family left for America with nothing. For the people of the Kurdish diaspora, images represent so much more than just the image in the photo. It’s about my family’s own story about coming form Kurdistan. It’s something they don’t want to talk about. It’s too painful. I found this as a way to rediscover my family’s past. There is a cultural barrier between me and my parents. This project became a way to communicate with and better understand them as well as my genuine self. Southern culture and Kurdish culture actually have a lot in common, but it’s not always recognized by either side. Southern culture is about bringing people together over food, and that’s very much the same as Kurdish culture.

JN: Nuveen, you also use old photographs in your work.

NB: We lack documentation not only in our homeland but even more when we left Kurdistan. Reusing these images is important because there’s so much history that’s been lost because we don’t have a country. When I go to a museum and see artifacts from Turkey or Iran, I think “These might have been made by a Kurdish person.” But you never see that. We’re juggling two cultures here, but in other places they’re also considered Turkish or Iranian. Kurds are truly a fucking displaced people.

BA: Nashville has the biggest Kurdish population in the US, but that’s not something I expect everyone to know. Kurdish people mostly live along Nolensville Road and in Antioch because they want to live together to preserve this community.

NB: The Kurds in Nashville are even more traditional than the Kurds in Kurdistan. Leaving their home has made them hold on even tighter to certain aspects of the culture.

BA: Yes! At weddings in Nashville, everybody wears traditional Kurdish clothing. But back home, in Duhok, Kurdistan, everybody wears Western suits and gowns and dresses.

Beizar Aradini and Nuveen Bawari’s two-person exhibition Third Culture Kids is on view at VERSA in Chattanooga, Tennessee, through September 7.