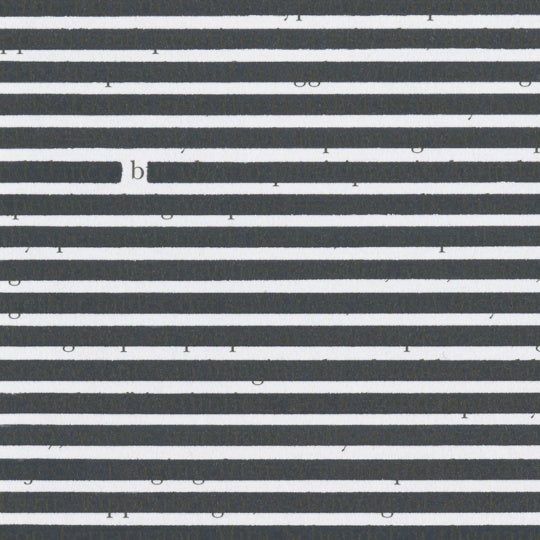

Like the celluloid reels which predated the ever-briefer bites of video that now share the same name, the modern phenomena of “scrolling” has its linguistic origin in the long, thin strips of fabric that were once used to record and pass on information.[1] Unlike a book chopped and stitched back together into separate numbered pages, a scroll unfolds non-hierarchically and continuously; within its length, the reader’s position in relation to any opening or concluding chapter or thought is lost. Instead, an endless stream emerges; there is no beginning or end.

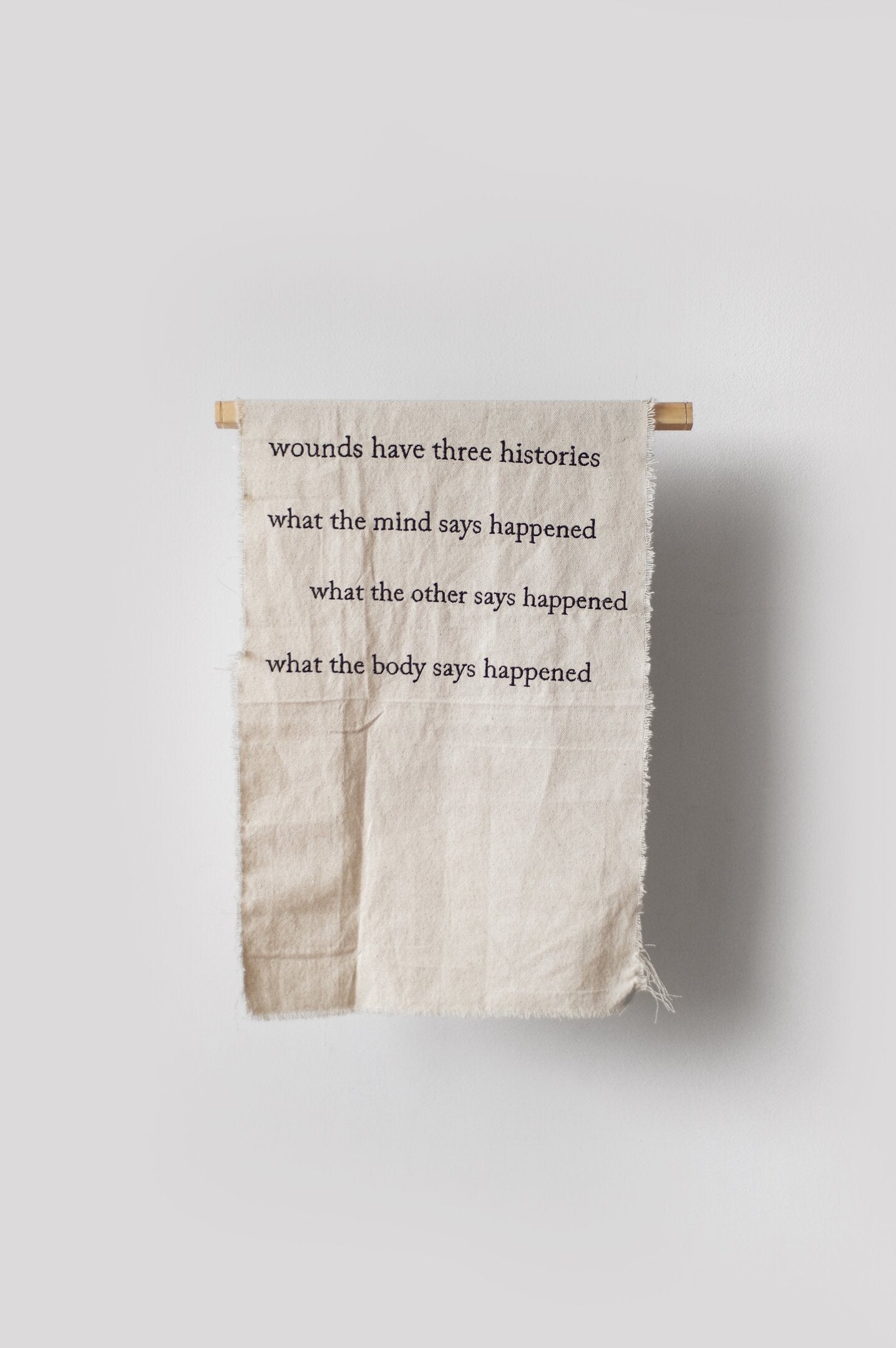

Nadia Tahoun’s textiles hang off the wall like linen waterfalls dropping off short wooden cliffs; they gather on the floor of the gallery or trail off into shadowy nothingness at the end as if to imply that the scribe has just stepped away and will return to the project momentarily. They gesture to the position of history writers while insisting that they have not arrived at the end of writing history, because surely there is more fabric to be filled, and more hands reaching resiliently each day to do the work of filling it.

Tahoun calls the series Szmatas (2022-2025), which comes from a Yiddish word meaning rag or towel.[2] “I like that word because it’s kind of a word that has no precious meaning,” Tahoun shared in an interview. “It’s art that’s been on walls and everyone cares for it very preciously. One showed last week in upstate New York at Harana Market, and it started to rain and someone was running inside to protect it, and I said, ‘No, leave it outside, I want to see how it looks wet!’ and they looked at me like I was crazy. It’s cloth. I really like the idea of the continuous flow, and not being too precious with it.”

In 2023, Tahoun worked with Amnesty International and the Circle of Brotherhood to host a workshop in the Brownsville neighborhood of Miami for students not served by the county’s public schools. The workshop was transformative for Tahoun, who was inspired to pursue her Masters in Social Work and advocate for more trauma-informed curation practices that better serve all artists. For the artist, this meant creating spaces that can support storytelling around histories of violence without re-traumatizing those who hold these stories in the first place. “Since I’ve graduated college and gotten older in the space, it’s just more and more visible that there are so many shows and practices where the nervous system is not at all considered. I mean even myself, since the genocide kicked off in a more severe way in Palestine, I’ve been to so many shows where a Palestinian has not even been considered in the curation, and it’s a pro-Palestinian show,” Tahoun shared in an interview. “What if this healing or trauma-informed framework is brought to art spaces, to places that have way more access and privilege? Why can’t it be everything? I’m sick of walking into white wall spaces, and seeing a nice essay about something horrific, but there’s not a lot of care in the space about the bodies moving through it.”

Tahoun’s family is Palestinian American, and she credits her interest in history keeping and archive making to the practices she observed in her family growing up. Partially in response to the silence and lack of support mechanisms provided by large arts institutions in the wake of October 7, she developed “an archive is a space for gathering.” The recurring online workshop and support space aimed at helping artists and creative practitioners reckon with their positionality as culture preservers in a time of staggering change. “Naturally, I always end up talking to artists about being the archivist of their family because they almost always are. They’re the ones collecting things, who see things differently. It wasn’t important for my siblings to do that until my grandfather died. My grandfather was a part of the Nakba, and he was forcibly removed from his land in Palestine. There was a lot of regret after he died, like we could have done more. I think so much about how the Palestinian resistance exists because we are a people that hold onto our traditions so strongly. We are hard to erase,” Tahoun shared.

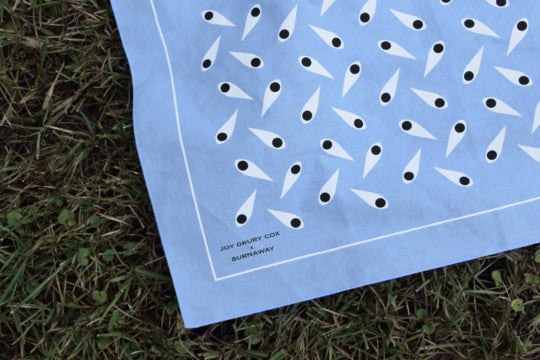

In 2019, Tahoun and her partner Cesar Castro started Flower Shop Collective (FSC): a studio, gallery, and general support space for artists from the Global South that is based between New York and Tahoun’s hometown of Miami. The name came from their first show, which was held on Valentine’s Day. Reflecting “the bouquet of experiences” that different members brought to the space, which often partnered with other BIPOC-owned spaces like Storm Books & People near their physical location in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, both spaces were abruptly forced to close their doors earlier this year in May due to rent increases, with just a few weeks notice.[3] When I met with Tahoun for the first time, shortly after she had received this news, she still felt excited for the collective’s future. She expressed how this change would help them be more nomadic and serve artists in different locations and circumstances. “I’m proud of what we did with that space but excited for what is ahead,” Tahoun shared. “I would love to be able to support artists outside of New York more and bring this work back to places like Miami.”

Like the scrolls which Tahoun constructs out of long strips of cloth, her organizing work speaks to a belief in collective histories and futures which resist the discontinuity and linearity of a cut page.

At their former location, FSC was known for providing artists with both the physical tools and space to fabricate work in different mediums. Community guidance on navigating the commercial and organizational aspects of the art world was also provided to those in the community. The studio regularly hosted Critique Nights, where members were encouraged to share and provide feedback on each other’s work. This practice encouraged learning and collaboration across disciplines, as well as reflection about the shared experiences that bind and inform a greater critique of institutional power and censorship.

Flower Shop Collective has worked with artist-run spaces in Miami to show work in a trauma-informed and uncensored way. During Miami Art Week 2023, they hosted a week of programming at Tunnel Projects in Little Havana that tackled the ongoing violence in Palestine and the intersectional needs of Miami’s creative community through a poetry reading and bilingual curatorial tours of an exhibition featuring four Palestinian artists. Tahoun remains connected to collectives working there, and would like to establish a physical location there in the future. “It kills me what our people have to go through right now in Florida. There are people doing great work, but they lost their NEA funding. What sucks is that I’ve seen so many organizations post the letter that they lost that funding and then they raise way more privately. Then there are the people that have non-profits but who don’t have access to that privilege. Who can’t go to Miami Beach or Park Slope brownstones and raise a bunch of money in one night to replace that loss. What happens to them now?” Tahoun shared. “What happens in Miami and Florida is just the start of what is coming everywhere else. I’ve always believed that, when it comes to immigration policy and everything.”

Like the scrolls which Tahoun constructs out of long strips of cloth, her organizing work speaks to a belief in collective histories and futures which resist the discontinuity and linearity of a cut page. Even in difficult moments, like the loss of Flower Shop Collective’s physical space in May, the work resists the temptation of an easy ending, and continues on.

[1] “Definition of Scroll.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Accessed September 29, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/dictionary/scroll.

[2] Nadia Tahoun, interview by author, Zoom, August 6, 2025.

[3] Nadia Tahoun, interview by author, live, May 6, 2025.