“The people who created Guede needed a god of derision. They needed a spirit which could burlesque the society that crushed him.”

ADVERTISEMENT– Zora Neal Hurston, Parlay Cheval Ou (Tell My Horse)

Prologue

History is not as simple as genres or borders, nor is it kind. Much more like the bracts on a boll of cotton, sharp and prickly, the razor-sharp leaves of sugarcane, a pricked finger on a banned spinning wheel, a queen’s poison comb, and later, the apple that attempts to put her rivals, Sleeping Beauty, Snow White, and their histories to sleep. Thorns draw blood, its victims enticed by the rose’s fragrance. Just what were those silent, deposed princesses dreaming about all those years? And what do they and their descendants have to show for their scars, generations of cultivating those brutal plants in the land of happily ever after?

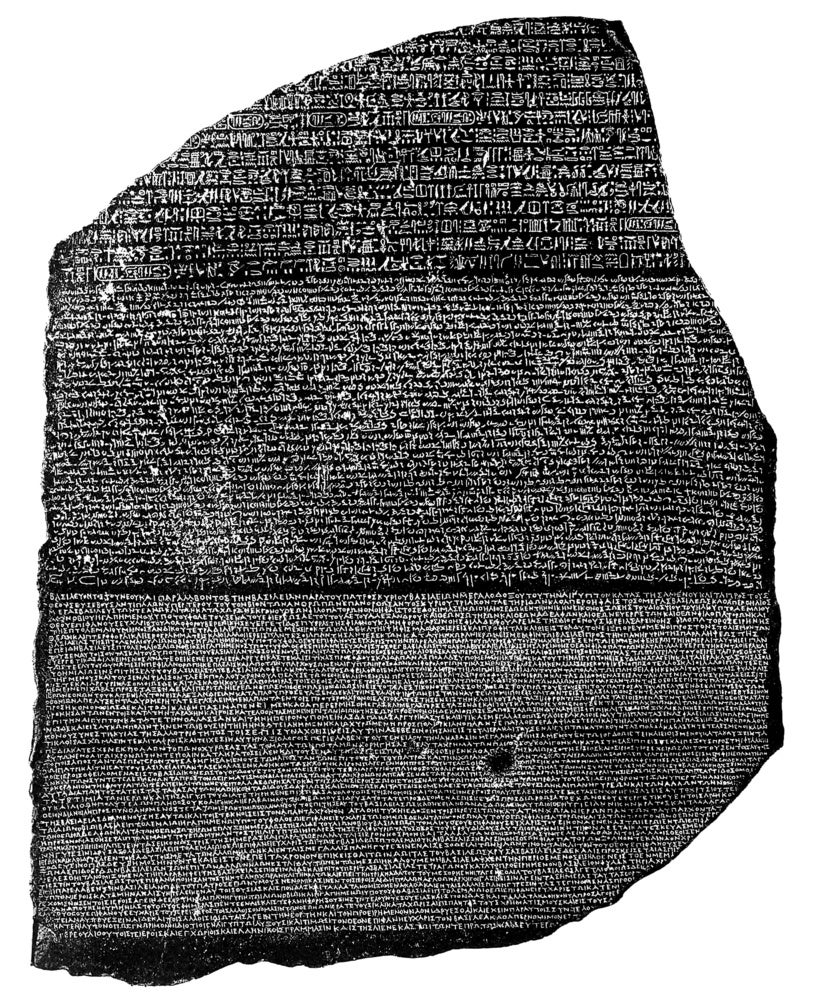

The year 1799 was auspicious. Nearly a decade into the Haitian Revolution, the French Revolution came to an effective end with Napoléon Bonaparte’s coup. (Born Napoleone Buonaparte in Corsica, he later adopted the French spelling of his name. His birth year, 1769, coincided with Corsica coming under French rule.) During his ultimately failed campaign into Egypt in 1799, Bonaparte’s officers discovered a black granodiorite stone near the village of Rosetta on the Nile Delta. Etched into the stone was a text written in three versions—in Ancient Egyptian in hieroglyphic and Demotic script and in Ancient Greek. Famous for being the key to the translating of Egyptian hieroglyphs, the Rosetta Stone was one of several carved stelas placed throughout Egypt during the “Great Revolt” (206–186 BC), in which native Egyptians rebelled en masse against the Greek rulers of the Ptolemaic Kingdom. Detailing the Ptolemaic victory, the stone served as Hellenistic propaganda for a volatile ancient world in which Indigenous people and the desires of an empire clashed.

Less than five years after the stone’s discovery, Bonaparte, approaching loss in Haiti, approved the sale of the Louisiana Territory to the United States of America. It was a sale that would double the size of the fledgling nation and encourage and engender the belief that westward expansion was a divinely ordained inevitability—commonly known as Manifest Destiny.

I.

Cowboy Carter (2024) is the second installment in Beyoncé’s planned trilogy of albums, which began in the summer of 2022 with the release of the euphoric Renaissance. Act II however commences with a funeral. Organ playing in the sanctuary, “American Requiem” begins with an avalanche of sitars, guitars, and synths. The tracks that follow on Cowboy Carter are autofictive, historical phantasms with multiple plots and possible outcomes presented simultaneously. A quarter of the way into the album, listeners are told that they’ve been tuned into the fictional radio station KNTRY Radio Texas. KNTRY Radio functions as an alter-archive of music history: the track “Smoke Hour ★ Willie Nelson” contains snippets of Son House’s “Grinnin’ in Your Face” (1965), Sister Rosetta Tharpe with Lucky Millinder and His Orchestra’s “Down by the Riverside” (1944), Chuck Berry’s “Maybellene” (1955), and Roy Hamilton’s “Don’t Let Go” (1958). The radio station’s “programs” are hosted by country veterans Willie Nelson and Linda Martell, the first Black woman to play the Grand Ole Opry. The next song on Cowboy Carter, “Texas Hold ‘Em,” follows this compact history lesson and features banjo scholar Rhiannon Giddens. A separate bounce remix of the song was released concurrently with the album, expanding, bending, and reconfiguring categories like dance, country, roots, and Americana.

At once a critique of the business of country music, whose own storytelling has been predicated on the erasure of its Black American origins, Cowboy Carter is also laden in its symbolism. I thought about Beyoncé posing sidesaddle on the album’s cover. Of the nine limited edition vinyl covers, one is a homage to Beyoncé’s mother’s maiden name, Beyincé. Tina Knowles recounted in an interview with InStyle magazine, the careless act of racism that resulted in the name’s misspelling on her own birth certificate and her choice to give that name to her eldest daughter. The accompaniment to looming and past cultural catastrophes, the songs consider the results of many of history’s accidents, tragedies, and plot twists—the silver spirit horse turns living steed on the wide release cover.

Alongside online debates about the album cover’s use of the American flag were the cyclical adjudications of what exactly it means to be Creole. Recalling stories about sore knuckles from speaking our outlawed language in the river parishes of Louisiana, I grew up learning to listen for understanding, to value it over comprehension. Forgive the contradictions and exasperations of old people who shouted instructions in a language they had been burdened with not passing on to their children and grandchildren.

II.

Years before I went to Cuba myself, I saw a picture of Beyoncé standing on a balcony there and wrote a poem about it. In 2016, I wrote an essay for The Nation, about the dissonance I experienced seeing people in Havana wearing American flag apparel. Among those wearing the stars and stripes with whom I had direct or third-party exchanges, I found a range of views about the empire that the flag represented, from ambivalence to indignance. There were some who found their clothing less an endorsement of the United States itself and more a dig at the bureaucrats in their own country. Revolution is a process after all. While there, a man cutting weeds nearby let me know that no Black person had ever stayed in my temporary host’s home before, further contextualizing the host’s incredulousness as she had been expecting two “Americans.” My strong conversational skills in Spanish had weakened in the years following Hurricane Katrina. While the population of Latino people had grown in the New Orleans metro area, the social fabric of which I had been a participant had faded. I could really only acknowledge that I had understood what he meant, but could not respond adequately. Yo entiende pero mi español es terrible.

Later I walked and walked, letting music quiet my nervous system. Exhausted, bewildered, and disconnected from the internet, I had Beyoncé’s Lemonade (2016) downloaded to my phone. I sang along to “Hold Up” through elation and disappointments on the island. There’s a callback to it in Cowboy Carter’s “Flamenco,” an echoing of both the mystic’s and the lover’s ecstasy, and their fatigue. Después del huracán estoy en la fluga . . . was that right? I ask the priestess I met outside La Virgen de Regla. Exhaustion made me almost cry. I had not slept well in days. I had spent the night before I arrived to Havana in a hostel in Cancun watching CNN crews pouring into Baton Rouge. National news cameras had not been in Louisiana in such numbers since Hurricane Katrina. Though others had been murdered by police in national silence before and since Trayvon Martin, Alton Sterling’s death in the Louisiana’s capital began a rupture, an onslaught, a turning loose of a host of hungry eyes, that once released could never be called back to its home. The second-by-second updates of Instagram and Twitter’s algorithm also grew in its cultural relevance alongside the highly publicized murders of Black Americans by the police.

Forgive the contradictions and exasperations of old people who shouted instructions in a language they had been burdened with not passing on to their children and grandchildren.

Before leaving Havana, I had been writing about the changing cultural landscape of New Orleans, its gentrification and confederate monuments. As a child in the nineties, I had watched the public-access debates that had removed most slaveholders’ names from New Orleans public schools and integrated Mardi Gras krewes. As an adult, I learned that the statue Peace, the Genius of History at Gayarré Place, just as Bayou Road forks into Esplanade Avenue, is a relic of the 1884 World’s Fair. That year, one third of the world’s cotton passed through New Orleans. One of several “peace” monuments in the South meant to represent reconciliation between the North and South after the Civil War, it was built for what was known then as the Cotton Centennial Exposition. The statue was constructed to show the world that the South was back in business and Reconstruction over. Atop it sits the Greek goddess Clio, one of the nine daughters of Zeus born to the goddess Mnemosyne (Memory) and the muse of history. The statue was gifted to New Orleans for the cotton centennial by the nephew-in-law of confederate general P.G.T. Beauregard. Like those granodiorite stelas erected by the Ptolemys of Ancient Egypt, it was meant to shape, in this case through aesthetics, society’s recollection (or not) of war, of revolt. Who was meant to rule and who must comply.

III.

I learned to love opera from my grandmother, who watched whenever one aired on our local PBS station and played cassette tapes of arias on her kitchen radio. My grandmother said that her aunts had explained the plotlines of French operas to her when its grammar failed her. The first documented staging of an opera in New Orleans, of André-Ernest-Modeste Grétry’s Sylvain, took place in 1796. Since, people of African descent have played a critical role in the development of opera and classical music in the city. As such, the inclusion of the aria “Caro Mio Ben” on Beyoncé’s “Daughter” feels apt within the album’s exploration of the music that formed the sound of American, yes, but more specifically Black Creole Southern identity. The back half of Cowboy Carter feels decidedly rooted in the Gulf South. “Alligator Tears,” “Desert Eagle,” ” Riverdance,” and “II Hands II Heaven” are sensory, romantic, and ecstatic. It sounds like an audio play and recalls my grandmother’s stories about how, in the country, they would dress nice and listen to the radio on Sunday. How having a radio was so special because it made their house a place to be on those Sundays.

Pines Village in New Orleans East smelled like bread and coffee every morning because of the factories nearby. The elementary school I attended there, Immaculate Heart of Mary, had a beautiful grotto on its grounds filled with statues of saints and virgins, some dedicated to neighbors we lost to murder or suicide. One had ended their life at their home across the street—so close to that classroom windows that students heard the shot. Or our dear friend’s parents, who were lost in a combination of both. We threw rocks at the sky when an airplane came to write “DUKE” in the horizon when the former grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan campaigned for governor. It was in my childhood friend’s older sister’s bedroom nearby that I heard Nirvana and Stone Temple Pilots for the first time and learned about a child rapper named Dwayne, who everybody knew would be a star.

When the longtime priest who had led the church associated with Immaculate Heart of Mary was accused of child sexual abuse almost three decades later, I argued to the point of tears with a friend who couldn’t accept the possibility. I was angry with her and she was angry with me. Both clinging to the sanctity and violence of our memories.

***

Allison “Tootie” Montana, Big Chief of the Yellow Pocahontas Mardi Gras Indian Tribe, died on June 27, 2005, of a heart attack he suffered in New Orleans City Council Chambers. He was there to advocate on behalf of Black Masking Indians disappointed with their poor treatment by police and city officials. This was just months before breached levees unleashed a wall of water that would subsume and destroy everything and everyone in its path, before all public-school teachers were fired and mental health facilities shuttered, and a few years before the housing projects would be torn down. In the years since, the confederate monuments of Jefferson, Beauregard, and Lee have been removed. A year shy of the twenty-year anniversary of Katrina, empty stone plinths and grassy neutral grounds have become valuable real estate.

The sixth edition of Prospect New Orleans’s triennial art exhibition will be preceded this year by the public art commissions of Louisiana-based artists and collectives under the auspices of its Artists of Public Memory program. I visited two of these commissions: kai lumumba barrow’s Abolition Playground (2023) and Chandra McCormick and Keith Calhoun’s Memoirs of the Lower 9th Ward (2023). I ask barrow if she thinks the structure of the triennial has the capacity to hold her ideas about carcerality. Struggle is protracted, barrow said to me, but each action contributes toward moving that struggle forward. We all must do the thing that gets us out of the bed in the morning and leave the rest to history. I listen with a lump in my throat, but I am attentive to her point.1

On my way to see Memoirs, I recalled Wangechi Mutu’s Ms. Sarah’s House, created in 2008 for Prospect New Orleans’s first iteration, then a biennial, just three years after Hurricane Katrina. A glowing structure in the form of a house, McCormick and Calhoun’s work is constructed from the pair’s black-and-white photography of Black communities in the Lower Ninth Ward in New Orleans. The couple’s photographic archive illuminates the structure and I search the photos for the faces of people I recognize and see a few. I recognize the white-clad women of the Ninth Ward’s spiritual churches, which at one time dotted its landscape, so much so, that almost no street was without a sacred space. I was called back from the waters that submerged our pasts. It was hard to leave them. I walked away heavy hearted that the structure would not stand through the duration of the exhibition.

***

Cowboy Carter ends the way it begins—in the sanctuary. “Amen” is an elegy set in a future time that imagines both destruction and survival. “The statues they made were beautiful, but they were lies of stone.” A fairytale, a myth, a fable, legend, patake, or parable, a religion, “a practice with no stable cosmology,”2 as a so-called expert once categorized the beliefs upon which I was raised—differences of category predicated on the faulty parameters of human belief, esteem, and regard.

And they crumbled.

Infants may be the wisest of humans. Certainly, the most honest, unencumbered by the concern for benevolence, they say frankly and plainly with their wailing, “I need.” Babies don’t care to be brave, only satiated. Babies believe that they disappear when they close their eyes. When I traveled to Cuba years ago with a friend, I left without one. The priestess had said a few things, but I had only been able to take it in partially. Family and friends can make you sick, that I had understood. Heartbreak gives way to me closing my eyes and vacating the past or the future for an ephemeral, aural present. Give me this feeling, give me music, to hell with all that or what may be, let me hold what I have.

Beyoncé’s “Freedom” has been leant for its official use to presidential candidate Kamala Harris’s campaign. The video of Sonya Massey’s murder by police in Springfield, Illinois, has gone viral and I find myself thinking about “Champion of the World,” a widely anthologized chapter from Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969). The excerpt depicts heavyweight champion Joe Louis’s victory over Italo Mussolini’s favorite Primo Carnera. Angelou recounts how those who had traveled from out of town to her grandparent’s store to listen to the bout on the radio made arrangements with others to stay the night. History had taught them that the road was not safe, especially in victory, Pyrrhic or otherwise.

Those are just stories that your granny told you, the white, self-identified expert on Haitian Vodou said to me from the audience of a panel on which I was speaking3. She was insistent on drawing a hierarchical contrast between spiritual practices in New Orleans and Haiti, all while speaking Kreyòl to the Haitian panelist, who pointedly answered exclusively in English.

This story is too large and complicated for heroes. Villains, though, abound.

Epilogue

Along with the discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799 was Bonaparte’s unrealized declaration of Palestine as a French protectorate and a homeland for Jewish people. It would be the British who would ultimately claim both ownership of the ancient stela and the initial carving up of Palestine, where a conservative estimate says more than forty thousand Palestinians have been killed in just ten months. Who is to rule, who must comply? Who is remembered, who is made to be forgotten, and how will this happen?

In 1849 Haitian President Faustin-Élie Soulouque, commissioned an investigation of reports of apparitions of the Virgin Mary in the palm trees at Sodo, Kreyol for Saut d’Eau in Haiti. Its name meaning waterfall, it is the island’s most visited pilgrimage site and was formed following an earthquake in 1842. A blue chapel was built for the Vièj Mirak (Miracle Virgin) a short time after the reports of the sightings4. The waters of Sodo are also home to the ancient and primordial lwa, the serpent Danbala Wèdo and his rainbow wife Ayida Wèdo, Lasirèn, and many, many others in Vodou’s spiritual system.

Water, the great constant of change. The sky, an abyss, space, or the sea, stretched out before us; there is no difference between the expanse of the clouds or the waters of the gulf. A sea of darkness, Sun Ra said.

Who is to rule, who must comply? Who is remembered, who is made to be forgotten, and how will this happen?

In Greg Tate’s text “Kalahari Hopscotch Or Notes toward a Twenty-Volume Afrocentric Futurist Manifesto,” he evokes Sun Ra’s philosophy that “as a Black American, you live on an existential and extraterrestrial world way off the coast of the place where America’s most paranoid and demonic live.”5 Some days I wake up in New Orleans and I feel trapped; other days, free. Every time it “threatens rain” as my great grandfather used to say, I remember how low and heavy the clouds hung in Havana before it rained. How so often it wouldn’t rain, despite feeling like I could reach up and touch the storm cloud above my head, the sphere-like wonder of an island sky. In Zora Neale Hurston’s Tell My Horse, in which Hurston recorded accounts of daily life and sacred practice in Jamaica and Haiti, she describes the ceremony of Tete L’Eau (Head of the Water) that she is allowed to attend in Haiti. At the ceremony, held while the moon is full and white, Hurston describes the gunshot fired that calls all of the houngan’s assistants to bow before he begins a liturgical song:

Maitre, Maitre, L’Afrique Guinin ce protection

Nous Ap Mande, ce d’lo qui poti mortel, protection

Maitre d’lo pour toute petites li.

Master, African Master of Guinea, we ask your protection. The water which is able to hear mortals, we ask your protection for all us children.6

[1] barrow, kai. Personal Interview. 14 November 2023.

[2] Comment from audience member. Panel: Bondye: Between and Beyond, New Orleans Museum of Art, 2018.

[3] Comment from audience member. Panel: Bondye: Between and Beyond, New Orleans Museum of Art, 2018.

[4] Elizabeth McAlister, “Sacred Waters of Haitian Vodou: The Pilgrimage of Sodo” in Celeste Ray, ed., Sacred Waters: A Cross-Cultural Compendium of Hallowed Springs and Holy Wells. Routledge Publishing, 2020, pp. 259-265.

[5] Greg Tate, “Kalahari Hopscotch Or Notes toward a Twenty-Volume Afrocentric Futurist Manifesto,” in Flyboy 2: The Greg Tate Reader, Duke University Press, 2016.

[6] Zora Neale Hurston, “Parlay Cheval Ou (Tell My Horse),” in Hurston: Folklore, Memoirs, & Others (New York: Library of America, 1935), pp. 500–501.

This essay is a feature release of Burnaway’s 2024 theme series Crush.