It’s 12:30 a.m. on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C., and there is a surprising amount of foot traffic six blocks from the Capital Building. I’m standing in front of this narrow mint green storefront, which once housed a beloved dive bar called Lil’ Pub, watching a Vito Acconci video piece through the glass. People milling up and down the street, making a late 7-Eleven run, stop to join me before heading back into the night. This enigmatic twenty-two-square-foot gallery, tucked into the façade of the adjacent CVS, has been the home to Triple Candie since 2021. Visitors are greeted by an understated sign; the gallery consisting solely of a shallow display window filled with cryptic arrangements of objects that provoke curiosity but offer little immediate explanation. A locked door beside the window bears the message, “Sorry, no entry.”

For those who stumble upon it, the gallery presents more questions than answers, and that’s exactly how its founders, Shelly Bancroft and Peter Nesbett, have always liked it. It’s difficult for me to stay objective or balanced as I’ve been a fan since my first visit to their old space in Harlem, NY, back in 2006. To have watched Triple Candie’s more than two decades and counting history of curatorial experimentation and intellectual play had long ago convinced me that they have the world’s most exciting, thought-provoking, unconventional curatorial program.

Since their start in 2001, Triple Candie began as a research-oriented curatorial agency run by two art historians who set out to explore the possibilities of exhibition-making as a critical, alternative practice. At the time, its mission was to present rather than produce exhibitions, inviting other nonprofits to curate exhibitions in its space, in order to contrast market-oriented institutions. The founders envisioned the organization as a nearly autonomous system, controlling as many aspects of conceptualization, production, and promotion as possible within their limited means. However, the recession that followed 9/11 made this strategy less viable.

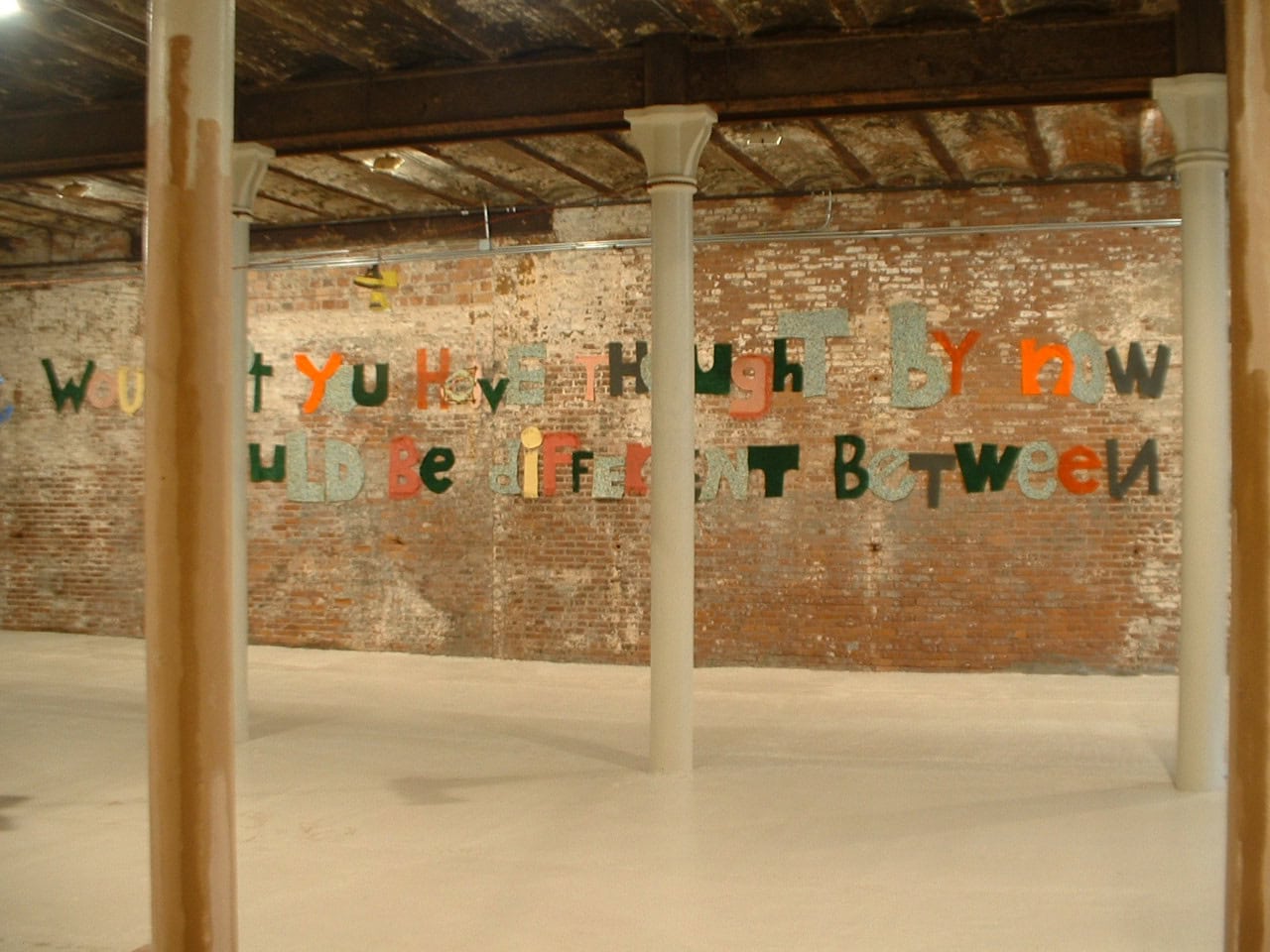

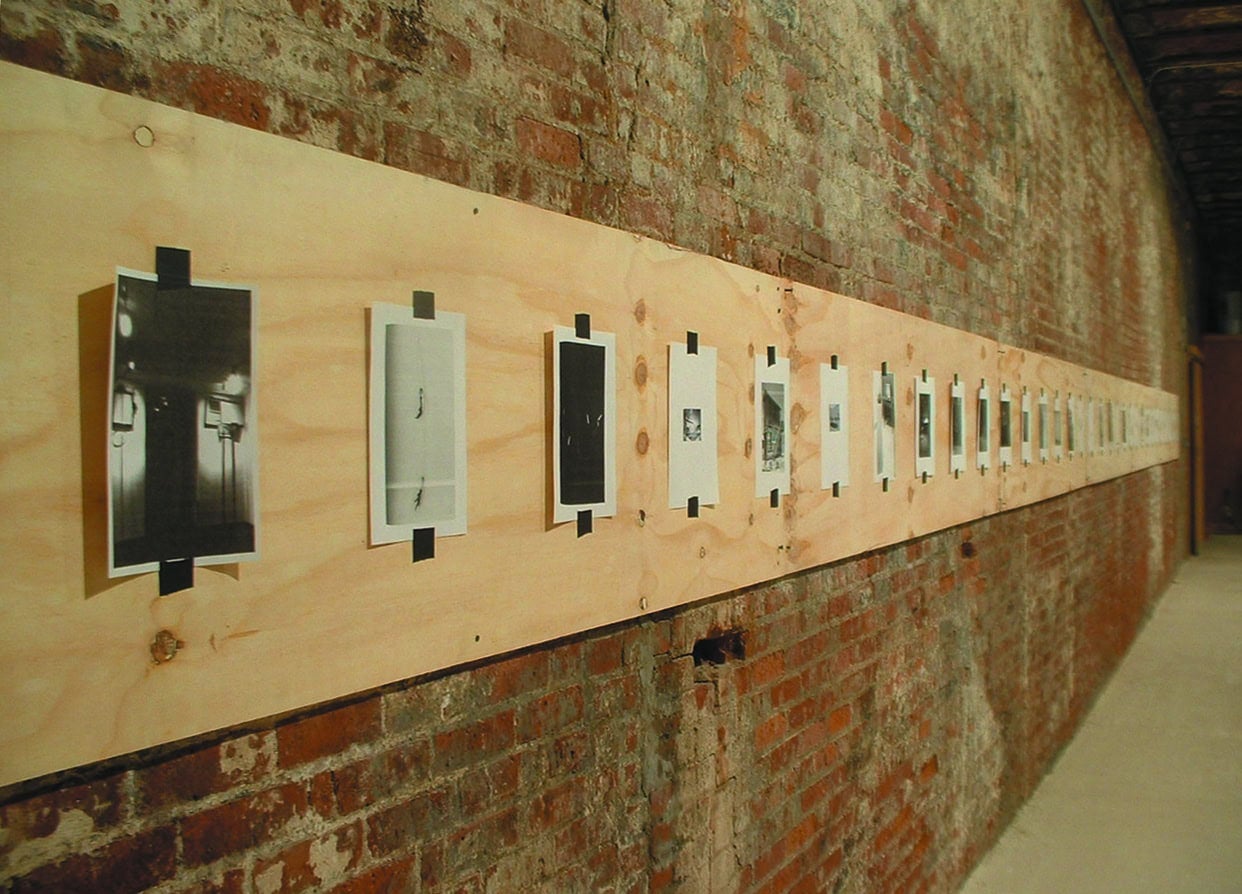

While most arts institutions set their mission and seldom, if ever, change it, Triple Candie is nimble, adjusting to time and place. Between 2001 and 2008, Triple Candie operated a big and beautiful 5,000 square foot space with exposed brick walls and concrete floors where they shifted their programmatic focus four more times. This began with a series of group exhibitions that brought together work from emerging and established artists, bucking the trend of focusing solely on emerging talent in New York’s alternative spaces. From 2004 to 2005, the gallery hosted ambitious solo projects by artists like Sanford Biggers and Charles Gaines, providing generous support, fabrication assistants, and on-site development for their works, turning the gallery into a studio that would be the envy of any artist. During the same period, Triple Candie launched their first major experiment, the Anonymous Artist Project I and II, where well-known artists submitted work without revealing their identities. This forced viewers to engage with the work on its own terms, without the influence of the artist’s reputation or background. The project highlighted one of the central themes of Triple Candie’s curatorial philosophy: that art should be evaluated independently of its creator’s biography.

And then, in the winter of 2005, they changed the game. In a world where commercial galleries and major museums dominated the landscape, Triple Candie sought to carve out a space where they could operate independently of market pressures. That is when they made a bold decision that would be impossible to stage in a more conventional context: they stopped working with artists entirely. Instead, Bancroft and Nesbett use reproductions, surrogates, models, and everyday objects to explore ideas about art history, cultural value, and curatorship. This shift was partly a response to the growing commercialization of the art world, which they found increasingly restrictive. Moving forward, they borrowed from museum practice and display. Think of life-size reconstructions, vignettes, or miniature displays, the methods that frame historical or cultural objects in a way that helps people understand their significance within a broader narrative. In these iterations, non-art objects were used to provoke thought or discussion or simply as a method of narrative storytelling. When they staged an exhibition such as 2007’s Flip Viola and the Blurs (Misrepresenting an artwork can result in a non-art experience of comparable value), in which they Bill Viola’s 1979-81 video Ancient of Days, and very literally flipped the projection, their approach challenged the art world’s fetishization of authenticity and originality. The press release read: “The exhibition cost $11.50 to produce.”

After intensive efforts to work with David Hammons, who lived in the neighborhood, their first exhibition in this new model was the 2006 exhibition, David Hammons: The Unauthorized Retrospective, a show made up entirely of photocopies and computer printouts of nearly 100 body prints, sculptures, drawings, performances, and installations of Hammons’ works. The exhibition was staged without the artist’s permission and stirred considerable controversy and conversation. I was instantly in love.

The curators expressed a moral obligation to exhibit the work of important, influential artists whose art has become difficult for the public to see. Artists “exhibited” by Triple Candie like David Hammons and later Cady Noland create works with strong social or political messages, often reflecting the experiences of ordinary people. According to the Triple Candie founders, when their art became inaccessible, it lost its potential to contribute to social or cultural conversations, limiting its impact and purpose. By making these works available, even through reproductions, Triple Candie aimed to preserve their relevance and accessibility to the public.

One byproduct of working this way, especially at the start, was the speculation that the artists were in on the joke. They were not. I’ve always remembered a story Bancroft and Nesbett told me long ago: when they arrived in the morning of the Hammons opening, there was a little sculpture sitting on the Triple Candie doorstep. It was in the style of the artist. They never sought proof or attempted to verify its origin, but at the time, they believed Hammons had left it as a symbol of “well played.”

In 2019, after years of operating nomadically and creating exhibitions for museums and galleries across the U.S. and Europe, Bancroft and Nesbett returned to a brick-and-mortar space with the new home for Triple Candie in Washington, D.C. Operating in such an unconventional space has allowed Triple Candie to continue their tradition of experimentation. They refer to their monthly rotating exhibitions as “curatorial riddles,” designed to provoke questions rather than provide answers. The resulting exhibitions are a mysterious mix of art and non-art objects and a countless checklist of books, paintings, gems, flowers, and items repurposed from previous Triple Candie shows. The aim of these displays is to challenge viewers to reconsider what they think they know about art, curation, and the gallery’s role. “What’s best for us,” Nesbett says, “is if a person who knows absolutely nothing about what we are doing finds pleasure in it.”

Despite its small size, the D.C. gallery has become vital to the Capitol Hill neighborhood. Unlike larger institutions on the National Mall that cater to tourists or the broader art world, Triple Candie’s primary audience consists of locals who encounter the gallery as part of their daily routine. The space’s community relations consists entirely of word-of-mouth press releases, as many people who engage with the space are from nearby social services and shelters or are people making their nightly runs to nearby stores. While the average art viewer might see an exhibition once, the Triple Candie audience is one with repeated interaction; thus, they often provide the most detailed feedback on the exhibitions. As a small institution, they benefit from being responsive and responsible to their neighbors. As they phrased it, “It’s a true community project.”

When you feel like you’ve found a pattern or a clue to the riddles, they change the parameters again. On a recent visit, you could see the immersive installation through the windows before parking the car. Matching mops cascade in circular patterns, creating a sense of harmony over a nature-inspired wallpaper’s magical, fabricated world. There were two hornets’ nests, one cradled in a pair of purple mannequin arms. The corner contained a clue, a metal folding chair marked, ‘Goudy Wildlife Club of Newburgh.’ Deep digging revealed that this was the Club’s janitor’s closet and a meticulous installation by the artist Matthew Lusk.

They refer to their monthly rotating exhibitions as “curatorial riddles,” designed to provoke questions rather than provide answers.

Bancroft explained that the riddles originate organically, “They’re often in response to objects that are immediately around us, which might influence what we do. We use the term ‘riddle’ broadly, hoping things remain open-ended with no definitive solution or answer. The shows can be interpreted in multiple ways. For someone on the street, contemporary art often feels like a riddle—something mysterious and unrecognizable, which can seem unsolvable and, because of that, off-putting.”

For more than two decades, Triple Candie challenged the conventions of exhibition-making, refusing to conform to the norms of the art world. This stance has earned them both praise and criticism and solidified their distinct and influential legacy. When asked about this, Nesbett said, “We’re doing something so unusual no one seems to want to copy us.” As they continue to create their curatorial riddles, Triple Candie’s work is a reminder that the most interesting questions in art often have no clear answers.