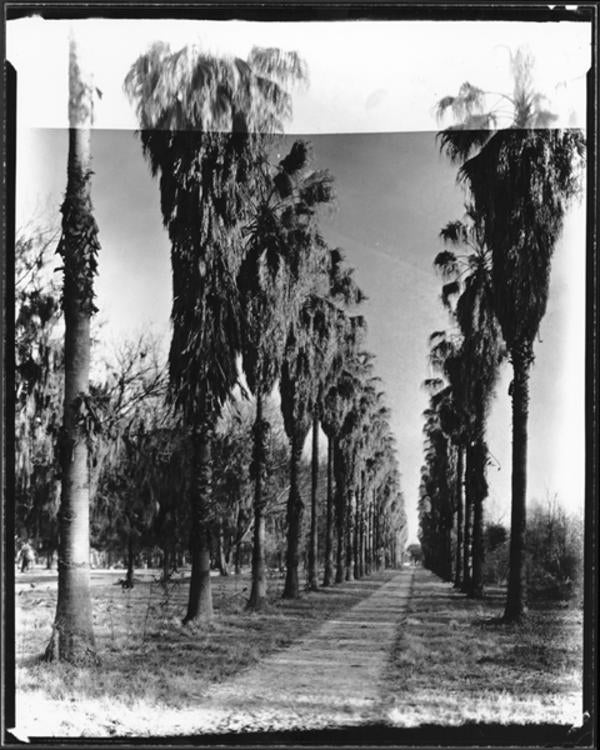

The New Orleans Museum of Art is located on the grounds of City Park, one of the city’s greatest gifts. I have retreated there countless times throughout my childhood and adulthood and have always been able to find adventure or solace in its sprawling thirteen-hundred acres. Slipping off into one of its myriad nooks, it is easy to forget the world outside and fall into an alternate, yet more insistently real, timeline. In the eighteenth century, the area which comprises today’s park was extremely watery—the lagoons in the park today are holdovers from this period. The land was occupied by many nations, including the Chapitoulas and the Houma, with the bayou, known today as Bayou St. John, serving as a shortcut of sorts between Lake Pontchartrain and the Mississippi River. Goods brought in by Native people via the Gulf of Mexico and Lake Pontchartrain would be offloaded along the bayou and then transported down a narrow ridge of land to the market at the mouth of the Mississippi. In the late 1700s, the land became the site of the Allard Plantation and was used to grow indigo and sugar. Later, it became a dairy farm before being lost to foreclosure and purchased by the American slaveholder John McDonogh in 1845. Following his death in 1850, the land was jointly bequeathed to the cities of New Orleans and Baltimore for four decades before becoming the exclusive property of New Orleans in 1890, at which point it was developed into a park that remained segregated until 1958. No matter what time of day or night I have entered the park, no matter the events of the day, none of these histories has escaped my thoughts.

This past April, the New Orleans Museum of Art presented Black Compositional Thought: 15 Paintings for the Plantationocene, a solo exhibition by artist Torkwase Dyson. Seeking to disrupt the claim of anthropocene theorists that all humans have contributed equally to the deterioration of the planet, Dyson utilizes the counter-framework of the “plantationocene,” which analyzes the effects of global plantation economies on the hoarding of resources, the exploitative consumption of those resources, and subsequent economic inequality. According to Dyson, “Black Compositional Thought”—the name for the artist’s working theory—“examines the ways in which waterways, architecture, and geographies are composed and inhabited by Black people’s bodies and how the properties of energy, space and scale can form networks of liberation.” Through abstraction, her paintings examine the architecture of structures that include the hull of a ship carrying human cargo; the narrow doorways of the “slave castles” on Goree Island, designed for one body at a time to be pushed through to captivity, making turning back an impossibility; and the sliver of light seen by the captif, who, thrown overboard, pulls themselves back onto the slave ship.

In early March, just before the onset of the coronavirus pandemic and the social distancing measures that would upend life and work for months to come, I directed a landscape photography session in City Park, near the Peristyle, for a now-postponed museum show. The exhibition, in its final form, will integrate conceptual frameworks from my artistic practice with an architect’s vision and architectural models to explore the way the discipline of architecture has interacted with race and Blackness. The goal of this collaborative effort is to refuse the inevitability of a present moment dominated by the extraction of natural resources and white supremacy by presenting, through performance and alternative architectural materials, a critical fabulation of what the present moment could have been instead and what the future has the potential to become.

The life of the park stretched out around us as we worked, with most other park-goers taking little notice of our set-up. I was trying to create photographs that seemingly erased the presence of a camera or my sight’s dominance over the state of nature. One person in the park, a jogger, seemed curious. In some of the test shots I took with my phone, his presence is a whir of motion: an arm, a leg, a torso creeping into the frame. The photos were aesthetically interesting, but it felt uncomfortable to hold on to a stranger’s image without their knowledge, so I deleted the shots.

Considering the landscape through the photographer’s lens rather than my own eyes, I registered the power of the camera and the frame in creating and sustaining “the record” and, by extension, its reinforcement of the status quo. Following public outrage over Ahmaud Arbery’s murder in February, the country again erupted following the deaths of George Floyd and Rayshard Brooks at the hands of police. The omnipresence of the heinous footage of their respective deaths, alongside the subsequent footage of protests, has caused me to contemplate more closely the photographs I worked on in City Park, particularly those that featured the anonymous jogger. In Jonathan Beller’s “Camera Obscura After All: Racist Writing with Light,” a chapter in his book The Message is Murder: Substrates of Computational Capital, the foundational presence of racism in the discipline of photography is examined, in part, through an alternate reading of Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida. Beller adopts critiques previously articulated by Fred Moten and Saidiya Hartman aimed at Barthes’s idea of the punctum or “prick of the real”—his claim that photography has the potential to exceed the expressive possibility of language. As examples of photographs that achieve this quality, Barthes uses images of enslaved people, which, Beller contends, construct a rhetorical situation that elucidates the chemical reality of the photographs but edits from view the historical realities that brought them to bear.

The now-viral footage of Ahmaud Arbery’s death and the subsequent ubiquity of his image in social media posts, reposts, and shares has left me wrestling with the wages of sight and the ways Black humanity is affirmed or undermined by the many lenses through which it is seen. In the spaces where light both enters and exits in Dyson’s paintings—through cracks in the hull of a ship or outside the slave castle doorway at Goree—what lies on the outside, through the hole, is either a life or a death distorted: not quite real, yet not total artifice. Barthes characterizes the image depicted in a photograph as “that which has been” and the act of being photographed, of being transformed from subject to object, as a moment of symbolic death. Ahmaud Arbery’s right to anonymity—in this case, the basis of his very subjectivity—was violated by the white men who demanded to apprehend him. It was pierced also by the camera lens that rendered him “visible” in our public consciousness, and a decision made by the person recording a video of the scene to abet a literal death.

The camera obscura, an invention important in the development of later photographic technology, projects an inverted version of an image through a pinhole of light onto a surface near its opening. In Beller’s book chapter, Harriet Jacobs’s autobiography Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl is utilized to illustrate the potential for a subversive disruption of the dynamics that situate racism between seeing and being seen. Published under the pseudonym “Linda Brent” in 1861, Incidents narrates Jacobs’s journey from captivity to freedom, one which included a seven-year concealment in a small attic at her grandmother’s house. Through a one-inch hole in this confined space, Jacobs saw glimpses of the lives of her children and family and watched the condition of enslavement itself unfold. Beller likens Jacobs’s positionality to the camera obscura through which the images of her children and others are projected and become a part of a visual field which she can observe. Jacobs herself exists somewhere between a subject—one who, in the space of confinement, reconstructs the framework for being free—and an object in the life she might have led in bondage outside of the attic. It is this positionality that Jacobs uses to disrupt her enslavement and reclaim her own life and image, which she later sets to the record herself. Her relationship to the many slippery dimensions of slavery and freedom, and her dual identities as both the fugitive slave named Harriet Jacobs and the free fictional character and author Linda Brent, place her at the crossroads of figuration, representation, and abstraction—a position analogous to the place of Blackness, as both an identity and a methodology within the discipline of photography itself.

So what kind of images, then, am I seeking? I asked myself as I deleted the jogger’s accidental appearance in my photographs in City Park. I tried to imagine shots of the landscape that did not undermine it as a place of refuge for so many, images that could create a visual language disrupting the conversation between the photographer-as-subject and the photographed-as-object. As the people of the United States continue to live and die with coronavirus, so will the rights of Ahmaud Arbery, Rayshard Brooks, Breonna Taylor, and countless others to live be adjudicated through a series of images provided to the public. Old patterns arise amid a new crisis. Death rates for Black coronavirus patients have been alarmingly disproportionate. Photographs of these harrowing moments have been praised for that punctum of the real that Barthes sought and are, again, informed and animated by Black suffering and death. Conversely, projects like “See in Black,” a collective of Black photographers donating proceeds from their work to organizations supporting the movement for Black life, declare a disposition toward their subjects that rejects objectification. How, then, does one do that in a discipline so mired in the practice? How does one define such a practice? What are the ethical boundaries and expectations between the Black photographer and his or her Black subjects that distinguish them from the discipline’s extractive history?

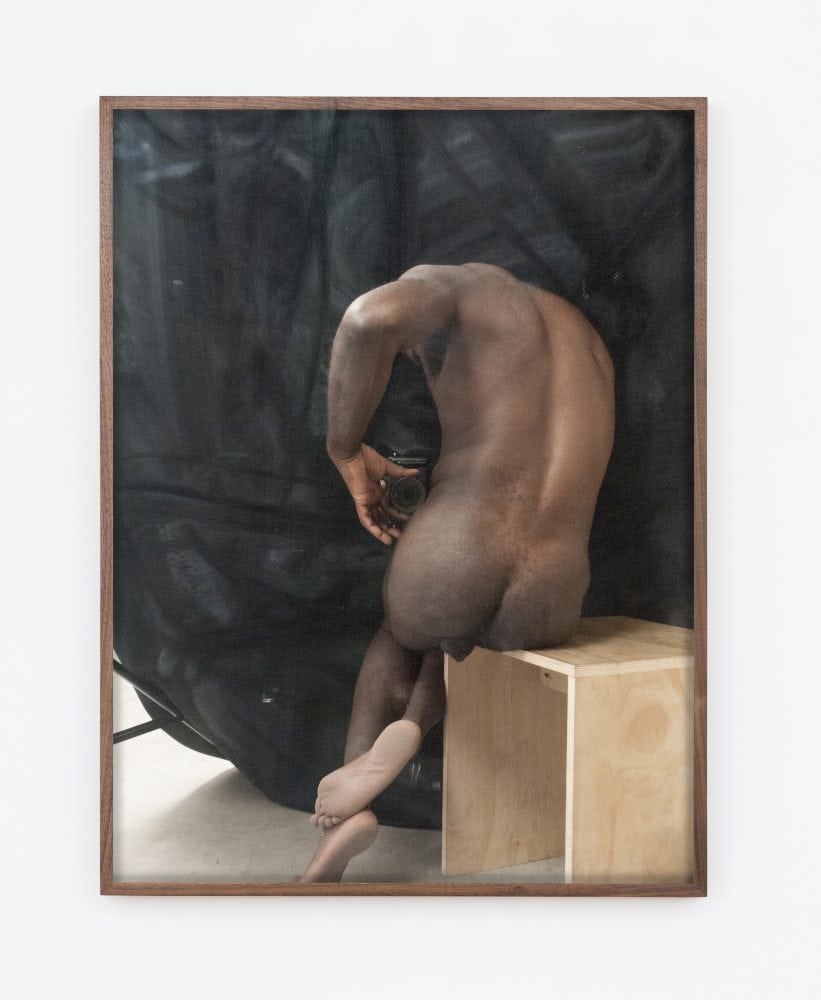

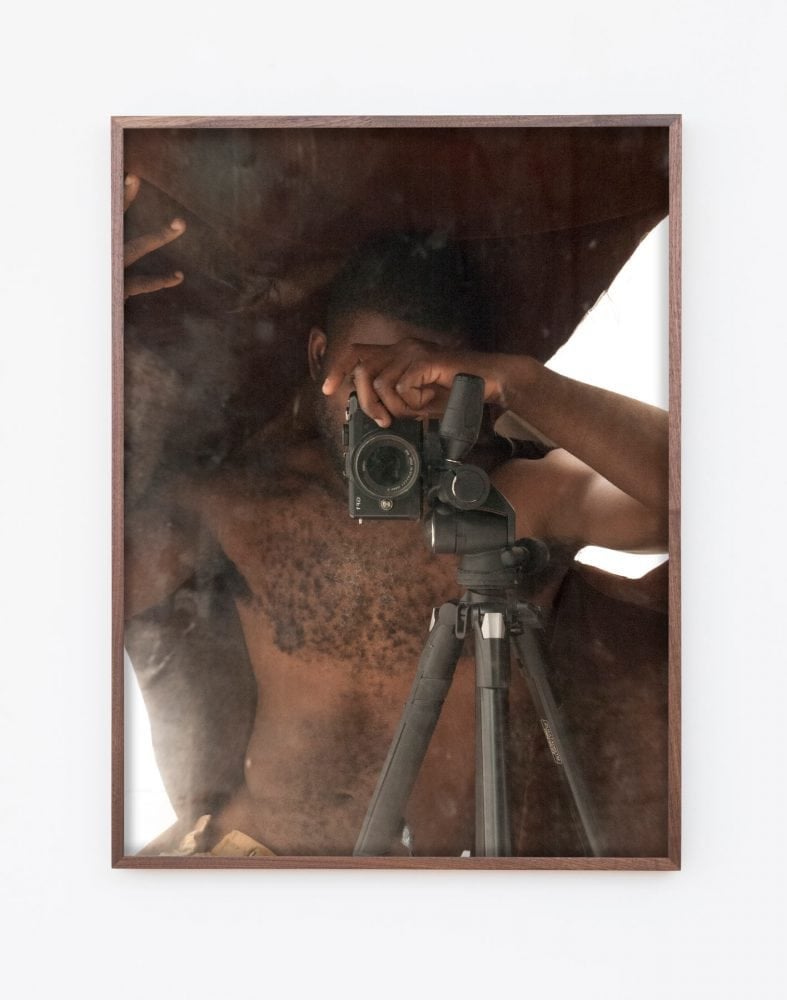

Photographer Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s work situates itself very decidedly in the middle of this ongoing and growing conversation. His long-planned solo show at Vielmetter Los Angeles has been postponed due to the coronavirus outbreak. Looking back at his contributions to exhibitions such as Implicit Tensions, the 2019 Robert Mapplethorpe retrospective at the Guggenheim, Sepuya’s photos echo many of the elements of Mapplethorpe’s while directly engaging questions surrounding agency. Sepuya’s series of nude self-portraits engages the entanglement between Blackness and literal blackness in the functional processes of photography. For his “Darkroom Mirror Series,” Sepuya uses a dark cloth to envelope his camera and a mirror to create self-portraits that reflect the mirror’s surface imperfections. Sepuya combines present-day technology with a camera-obscura-like technique. The image appearing on the mirrored surface depicts an active subject, one who is in a frame of his own making. In Mapplethorpe’s infamous “Black Book” series of highly eroticized and, many contend, exploitative images of Black male nudes, the subjects are stationary, frozen in the state constructed by the gaze of white male desire. Sepuya’s self-portraits return this gaze and ask the viewer to consider where they see or don’t see their gaze landing when consuming the image.

Are you an art lover or a voyeur? An observer or a participant? Do the images please you and, if so, is it joy you feel or the pleasure of consumption? Is Sepuya’s reflection free of the questions that make Mapplethorpe’s rendering of the Black male body rife with criticism to this day? Does it desire to be? What is this bind between desire and the unfree that makes autonomy for Black subjectivity so difficult to render? In Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents, it is her master’s unchecked desire to consume that drives her into the attic—the space that would become her “darkroom”—where she is able to imagine and configure freedom. Her body exists absent of the immediacy of physical freedom yet it is dually free from its racist and gendered constraints. In this darkroom of the fugitive, Jacobs’s body escapes the binary and is therefore able to determine a radical path forward. Analogously, the space that Sepuya creates beneath the dark cloth and with a mirror is one where many Black photographers emerging in this moment, so affixed to the hypervisibility of Black death, might want to spend some time. What you see reflected on the mirror’s muddied surface is a way to see yourself in your Black subjects that is, perhaps, a bit deeper than the erotic perfection frozen in time by Mapplethorpe.

Imagine that on that fateful road where Ahmaud Arbery jogged in Georgia the cameraman had made a different decision. Instead of capturing that moment of death that Barthes describes, imagine him becoming an actor in his own production, choosing to interrupt the conversation between photography and racism. Imagine him stepping from behind the lens, as Jacobs does in her autobiography, to write a narrative challenging the institution of chattel slavery and appearing, for a moment, in the same frame as Arbery. Visual language that relies on Black suffering, or juxtaposes its joy against its absence, continues a dialectic that encourages humans to act in accordance with a deadly script. In our varying degrees of isolation and confinement, the formulation of strategies toward a better way to live become necessary.

While uprisings and protests have been underway, monuments to slaveholders across the country have been ripped from their plinths, including the bust of John McDonogh in New Orleans. The day I visited Dyson’s Black Compositional Thought, I considered McDonogh’s early-nineteenth-century manumission scheme in which enslaved people could “buy” their deportation to Liberia after fifteen years of labor. The abstract shapes created by Dyson became new stories as I imagined the persons and personalities of those who animate these abstractions. As such, it is that beam of light—that ethereal moment before the image is “captured”—where freedom and autonomy may lie for Black subjectivity, where the existence of a new or fabulous visual language for Black life arises and introduces the possibility for action, one that might mean Ahmaud Arbery could be alive and jogging again today.

Torkwase Dyson’s solo exhibition Black Compositional Thought: 15 Paintings for the Plantationocene was on view at the New Orleans Museum of Art from January 24 through April 19, 2020.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s solo exhibition A conversation about around pictures is on view at Vielmetter Los Angeles through July 25.