Since its inception, photography has been a crucial medium through which generations of Black people have been able to see, imagine and expand our futures.

In her influential text Art on My Mind: Visual Politics (1995), the theorist and writer bell hooks makes clear the central role of photography in a collective understanding of Black life: “Cameras gave to black folks, irrespective of class, a means by which we could participate fully in the production of images. . . . Access and mass appeal have historically made photography a powerful location for the construction of an oppositional black aesthetic.”1 It is within this tradition of artistic resistance that the Houston-born artist and visual activist Irene Antonia Diane Reece lives and breathes.

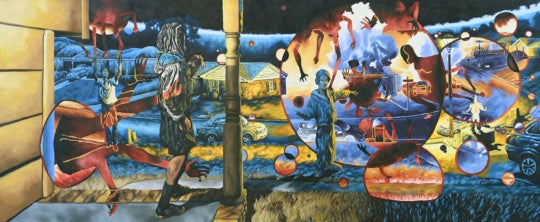

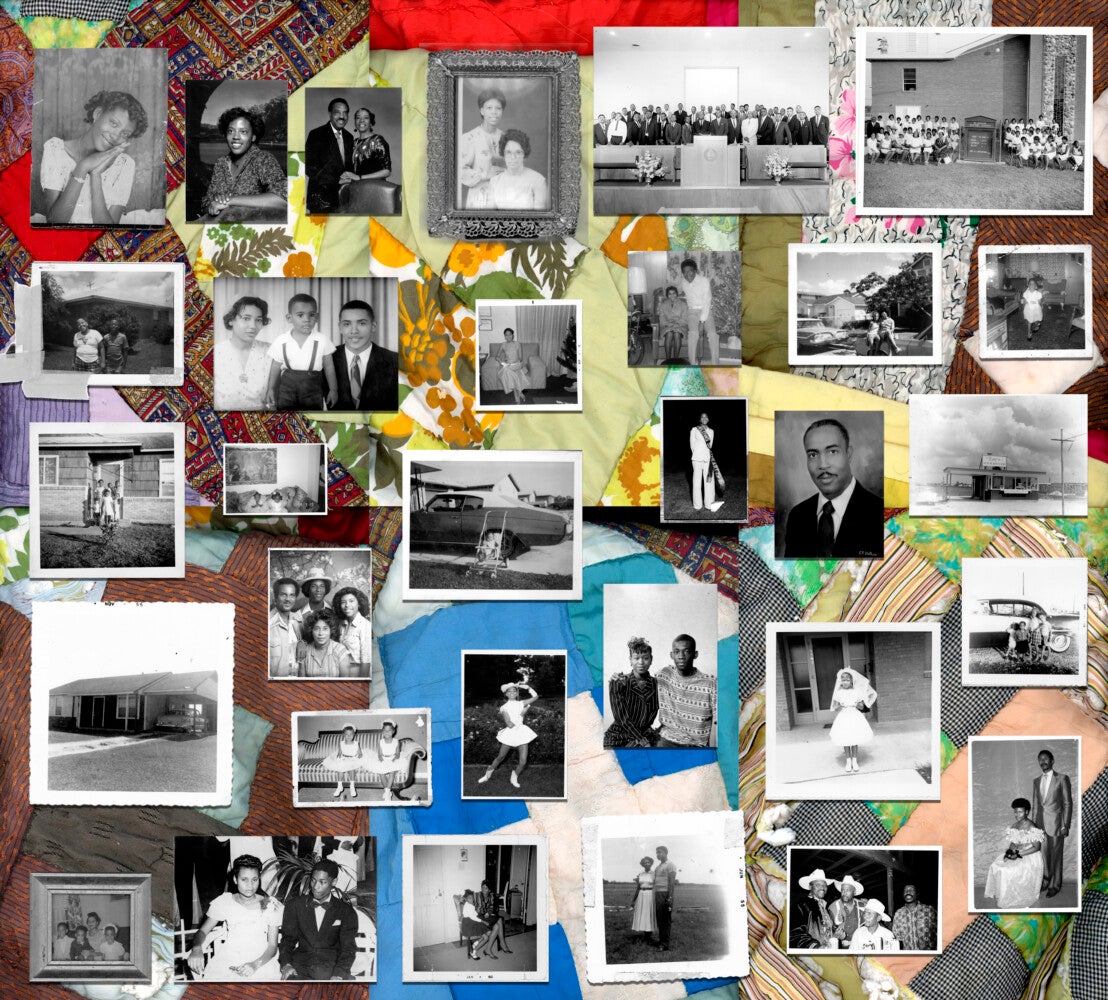

Reece is an image maker who builds immersive, often altar-like installations that embody a genuine commitment to preserving her family legacy. Each body of work fuses newly imagined photographs with archival or vernacular imagery, text, fabric and objects that often evoke a sense of intimacy. Reece’s Billie-James (c. 2016-ongoing) series calls upon her father’s Black Southern heritage, collapsing time and creating a parallel between her experience with racial prejudice and her father’s memories of the civil rights era. Engaging her family’s archive allowed Reece to grapple with the otherness and isolation she experienced during her graduate studies in Paris. She incorporates images of grandparents, aunts, and extended family into her work as a way to grieve and conjure comfort from her loved ones— folks she knew and ones she never got a chance to meet. In 2019, her exhibition Home-goings drew material from the archives of Metropolitan United Methodist in Conroe, Texas and Houston’s Trinity East Methodist Church to explore liberatory traditions and practices of the Black church. Equally inspiring is her series Para Mi Luz (2021–ongoing), where the artist honors her Mexican heritage and matrilineal ancestry by restaging rooms in her maternal grandfather’s home. For Reece, these gestures of care, this commitment to returning agency to those omitted from history, are critical to how she seeks to challenge colonial power structures in photography. Her recent work has extended this consideration to the histories of local communities, including that of Houston’s first Black neighborhood, Freedmen’s Town and Sunnyside – the oldest historically Black community in southern Houston.

Born and raised in Southeast Houston, with her childhood home located near Sunnyside, Reece considers the neighborhood to be a key site of her upbringing. Sunnyside was established as a racially segregated plot in 1915, during the Jim Crow era, by H.H. Holmes, a white city councilman and developer. In its heyday, according to Reece, Sunnyside grew to become “another version of Black Wall Street in the ’50s—a sanctuary for the Black community.”2 The neighborhood has since been ravaged by time, with a fluctuating economy, a turbulent political landscape, and an overall lack of investment from the City of Houston at the source of its demise. Alongside the late Houston art giant Jesse Lott, Reece was selected to create a body of work that would become integral to Sunnyside’s newly imagined Health and Multi-Service Center (MSC). This center, like others across the city, supplies the neighborhood with recreational, health, and social services. The building’s makeover was part of former Mayor Sylvester Turner’s Complete Communities initiative, which targeted ten under-resourced neighborhoods across Houston.

For Reece, these gestures of care, this commitment to returning agency to those omitted from history, are critical to how she seeks to challenge colonial power structures in photography.

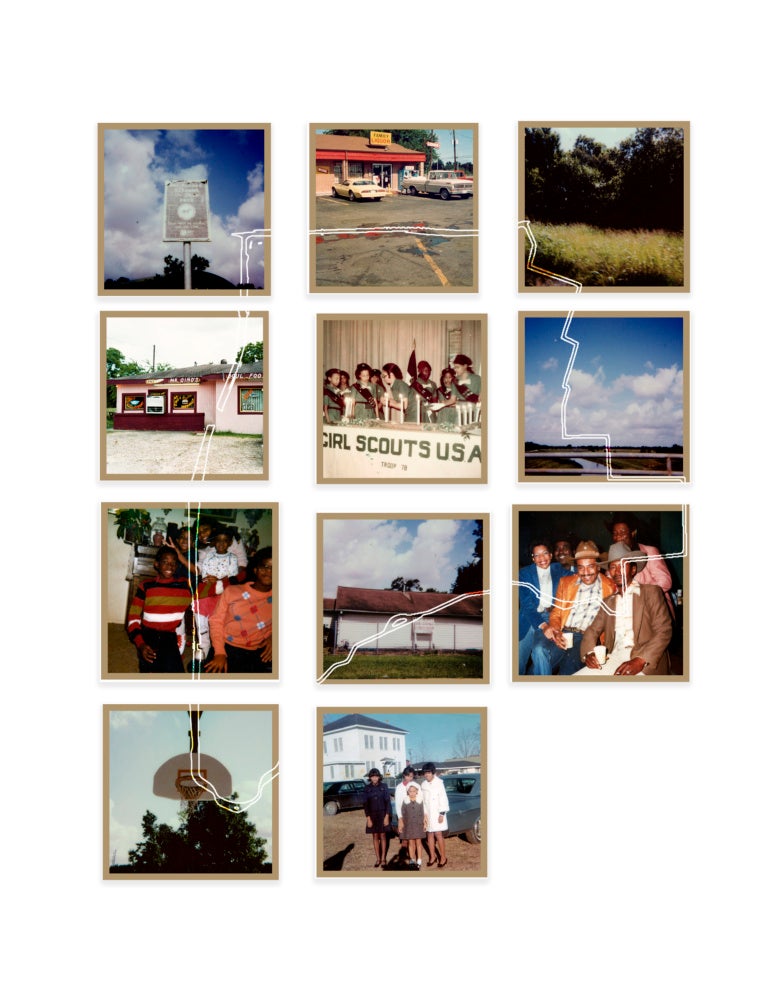

Toward the end of summer 2024, I visited the MSC to meet with Reece. Raised in Southeast Houston myself, I was greeted with a familiar warmth as I walked into the sprawling 57,000-square-foot building that opened a year prior. A security officer, seated in front of 11 square frames containing Reece’s images of the neighborhood, waved at me from the front desk. I passed the center’s clinic, where a small family comforted a wailing toddler. The voice of a cheerful bingo announcer spilled out from an auditorium packed with seniors on site for a midday game. On the right side of the MSC’s lobby was the central component of Reece’s photo-based installation, lovingly entitled That Sunnyside Pride (2022–ongoing). Seventy white frames of various sizes are arranged within a recessed wall whose perimeter is illuminated by a white fluorescent light. Behind these frames is a stretch of wallpaper Reece produced from three images: a large oak tree, a vintage photo of a Sunnyside home and Langston Hughes’s 1992 poem “Dreams,” recreated using alphabet letter pasta on a cerulean-colored backdrop.

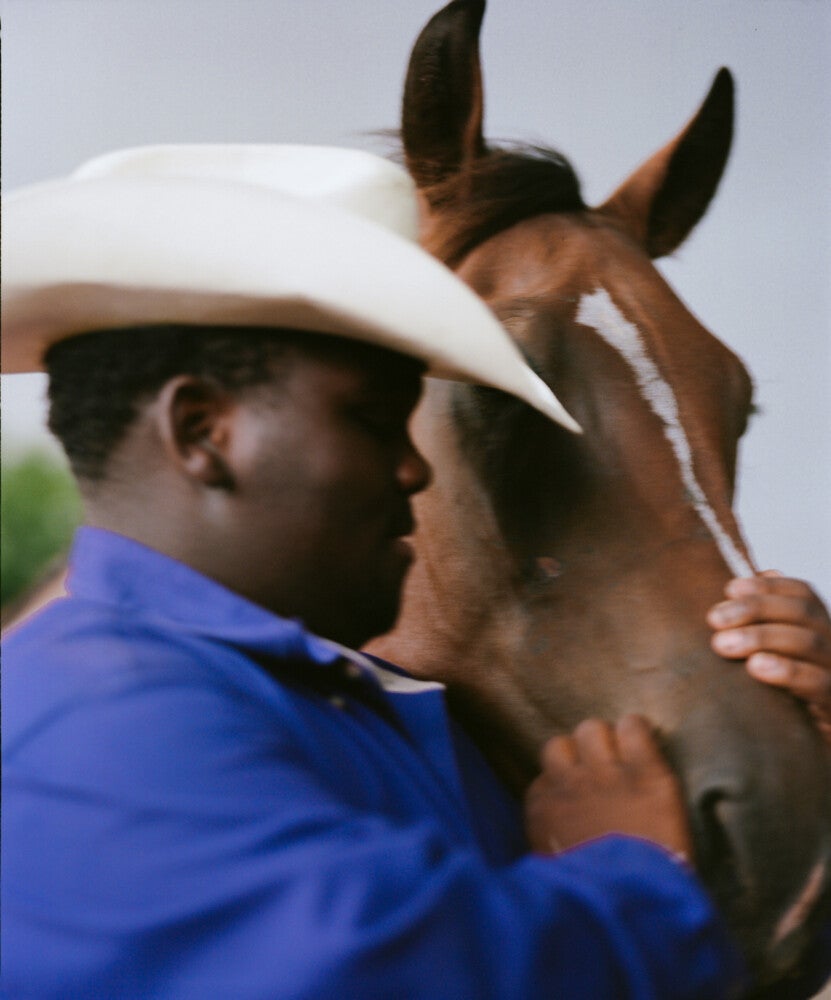

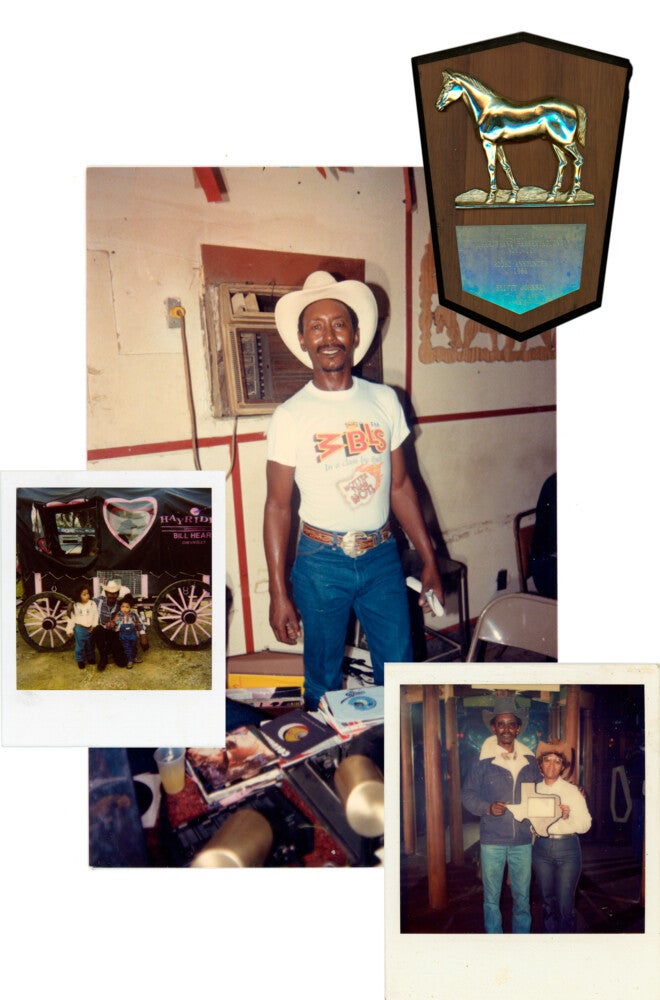

Using her medium format film camera, Reece photographed the descendants of Sunnyside’s prominent figures like Lorenzo “Smitty” Johnson, the first Black rodeo announcer in Houston, and Sandra Massie Hines, the self-proclaimed “Mayor of Sunnyside,” as well as civic club members; first responders; educators like the music innovator Elnore Boone; faith leaders; athletes; students at Worthing High School; business owners; and everyday people who make the community unique.

In That Sunnyside Pride, Reece set out to create an authentic and intimate archive of the neighborhood that would exist beyond the area’s ongoing gentrification. This commitment to authenticity guided her through the commission: Reece identified historic sites and individuals to include and invited intergenerational members from the larger community to contribute their stories. While working on the project, she visited residents’ homes to introduce herself and build trust with those whose grievances had long been ignored by city officials. “A lot of these folks have been fighting for equity for years before their kids were born,” Reece explains, “and now they’re older and their kids are fighting for the same thing.”3

Through her relationships with the residents, she could view and reproduce images, news clippings, and other ephemera from her subjects’ archives to be framed alongside the suite of new portraits. Once the portraits were complete, Reece organized an event inviting residents to vote on which images they loved the most. This ensured that whoever was represented was not dictated by the artist alone but also by the community.

Reece arranged each frame to reflect the bonds and the tensions within the community accurately. She told me her hopes for her work and how it might resonate with residents: “I want them to feel represented.” Her intentions were crystal clear as we stood before the glowing body of work. Upon seeing the final installation, Reece recalled, community members reacted emotionally to the images, rejuvenated by the work’s reflection of their history. “The majority of the people that grow up here know that the neighborhood is changing, that their voices aren’t being heard and they’re being erased,” the artist reflected. “I wanted to be clear that even though Houston is developing, you can’t erase us; we’re always going to be here.” Like much of Reece’s earlier work, this photographic series is notated as “forever growing,” demonstrating her passion for nurturing and sustaining these relationships as time progresses rather than abandoning them. Despite the challenges and negotiations involved in its completion, That Sunnyside Pride is a monumental offering that exemplifies Reece’s commitment to amplifying the unknown truths of the forgotten. It is a testament to the power of photography in Black life, as well as the tenderness and reciprocity needed to sustain communities for centuries to come.

[1] bell hooks, “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life,” in Art on My Mind: Visual Politics (New York City:The New Press, 1995), p. 57.

[2] Irene Antonia Diane Reece, interview with the author, Sunnyside, Houston, [July 2024].

[3] Reece, interview with the author, [July 2024].

This essay is the first feature release of Burnaway’s 2024 theme series Twang.