In Bermuda, the ‘still-vex’d Bermoothes’ of Shakespeare and the island I call home, hurricanes are a regular occurrence. Warm mid-Atlantic waters draw more than tourists, and low-pressure systems have brought chaos and destruction to the wider Caribbean region for millennia, obscuring quintessential images of tropical fantasylands. The storms are enduring ecological threads connecting the Caribbean’s pasts and presents, and their escalating intensity and devastation are undeniable markers of climate crisis. Beyond physical impact, storms also offer a conceptually compelling aesthetic methodology, particularly for Caribbean moving image practices. Artists Sofía Gallisá Muriente and Hope Strickland exemplify this methodology, demonstrating how the aesthetics of hurricanes can be reimagined as a dynamic, decolonial force.

Aesthetics are important in places that are defined by them.

In the Caribbean, a sanitised and exploitative visual language, tied to capitalist extraction and ecological domination, continues to distort challenging histories in favour of ‘paradise’.[1] The overwhelming majority of imagery depicting or inspired by the region is shaped by a colonial gaze, primarily catering to tourism and an external (namely, white) audience. This legacy traces back to the plantation era when these lands were seen as distant outposts sustaining life in the so-called ‘mother’ countries. Despite the Caribbean’s vast diversity, the continued impacts of the Plantationocene (a framework for understanding the environmental and cultural legacies of plantation economies) offer a means to examine the Caribbean as a cohesive whole while still respecting each country’s unique distinctions.[2] Within this ecological post-plantation framework, an aesthetics defined by absence, order, and transparency—tools of colonial domination—permeate. The region’s colonial history and present influence how the Caribbean is seen and understood not just externally, but within the region, determining what aspects of visual culture are platformed or, more to the point, commodified. The importance of materiality and contemporary art in repairing the region’s fractured history (and historiography), therefore, is informed by Plantationocene ecologies’ politics of absence or discovery.[3] This flattened visual language demands a counter-aesthetics to challenge its sterility, erasure, and hegemony.

In this context, hurricanes can be activated through contemporary art as a device to both read and exceed the Plantationocene.. Hurricanes defy human-imposed structures of control, ownership, and extractive order, emerging as powerful methodological agents of disruption. They dismantle colonial and capitalist landscapes indiscriminately, undoing the spatial logic of plantations, resorts, and other manufactured visions of paradise. The progressively violent impact of storms in the region, a direct result of the Plantationocene, shatters illusions of transparency and idealism this framework has created, replacing projected serene clarity with the chaos and destruction of nature’s unchecked force. If the Plantationocene explains the destruction of the environments and histories of the Caribbean in favour of a capitalist fantasy, then the indiscriminate nature of hurricanes can offer a means of re-reading these places, against the aesthetics of idyllism and colonial tourism, a dialogism that proposes hurricanes as an aesthetic method. As methodological agents they demand new frameworks for understanding Caribbean landscapes: not as static, owned, or consumable, but as volatile, interwoven with deep time and beyond mastery.

In their film works, artists like Hope Strickland and Sofía Gallisá Muriente counter invisibility, erasure, and the paradisiacal aesthetics of colonialism by embracing the chaos, opacity, and cyclical temporality synonymous with hurricanes. These artists disrupt the idyllic and sterile colonial narratives of the region, drawing attention to the histories and ecologies erased by these systems. In contemporary Caribbean moving image practices, the aesthetics of hurricanes serve as both a critique of the Plantationocene’s horrors that exacerbated them, and a methodology for transcending them. Their work introduces an aesthetics of instability, where clear waters are muddled, linear narratives are erased and destruction itself becomes a generative force for meaning. By placing ecology in dialogue with artistic practices, these works offer a means of historical reimagining: one that embraces complexity, resists erasure, and opens new pathways for understanding the region’s interconnected histories and futures.

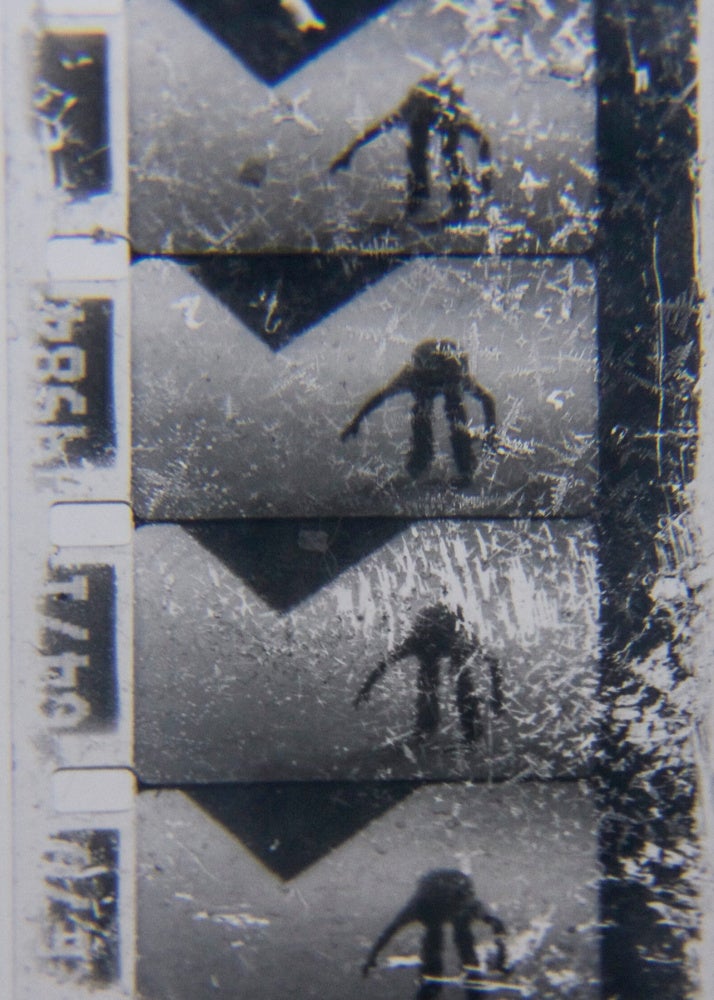

Reading Strickland and Muriente’s work through the hurricane’s dialogism, they each highlight and respond to the Plantationocene’s enduring ecological and cultural destruction. Consider Muriente’s Asimilar y Destruir (2017-2020) series (started not long after Hurricane Maria devastated parts of Puerto Rico) that explores how “climate conditions memory in the tropics.”[4] Created using 16mm film, one film features a home movie of Muriente’s grandmother, and another utilises footage she recorded of an ice rink on the island that the artist then deliberately damaged through exposure to Puerto Rico’s natural elements: salt, humidity, and mould, elements synonymous with hurricanes. The resulting deterioration fragments the footage, creating areas of decay that obscure the original images. These gaps and breaks in the celluloid emphasise the untamed natural environment’s disruption of Puerto Rico’s colonial projection as an idyll. Through deliberate erosion, Muriente underscores the fragility and impermanence of this fantasy while actively participating in its destruction.

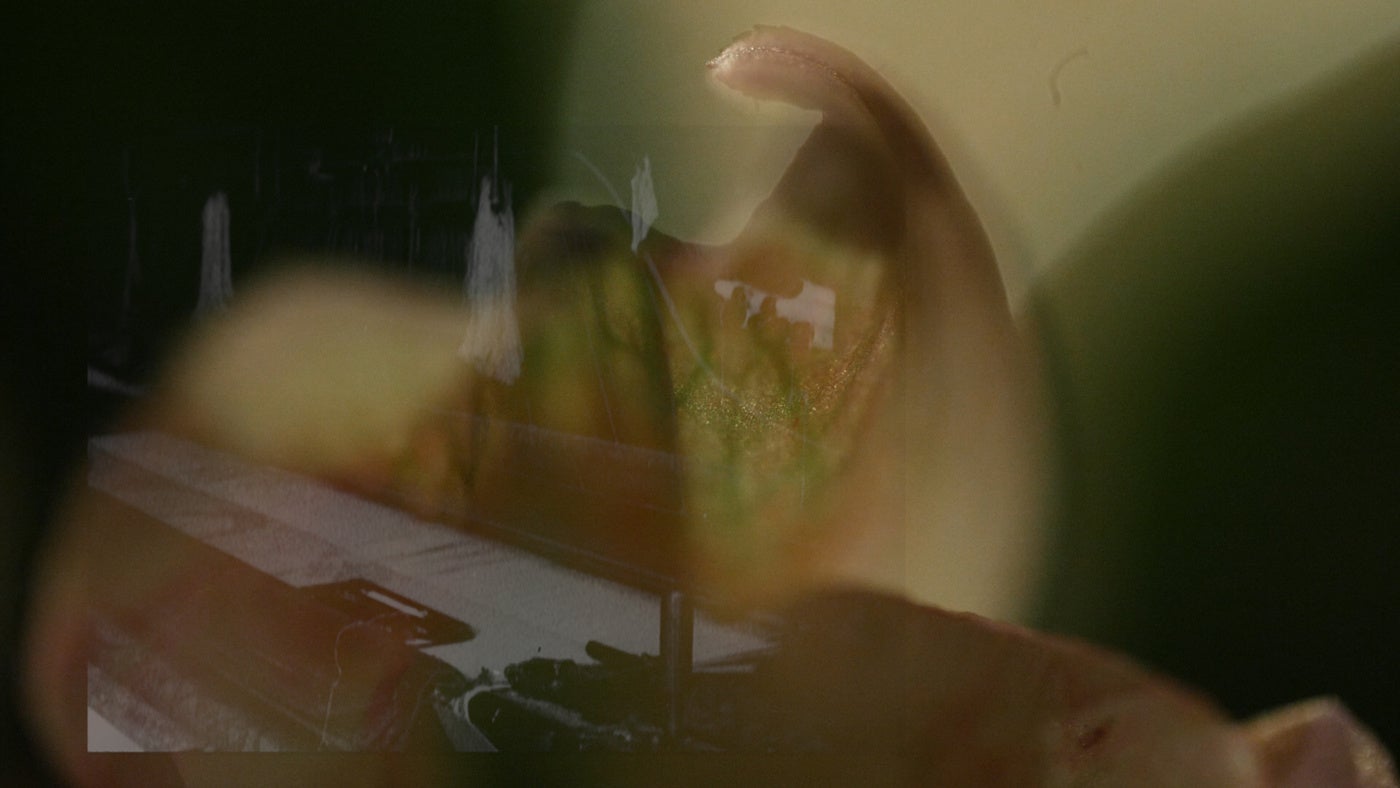

Hope Strickland’s If I could name you myself (I would hold you forever) (2021) employs a slightly different approach: engaging the hurricane as an aesthetic device through use of narrative opaqueness and temporal disruption, emulating the cyclical nature of Caribbean time.[5] Working between Jamaica and the UK, Strickland reframes the cotton plant’s role in acts of women’s resistance to enslavement, juxtaposing its association with plantation domination. Through a moving image collage of layered archival and digital footage, combined with close-ups and blurring, If I could name you myself (2021) cultivates an intentional opacity and transience. Resisting straightforward interpretation, it defies fixed temporalities and linear narratives, including those tropes associated with the region. Strickland’s deliberate disorienting imagery and manipulation of chronological narrative time not only counter the selective nature of historical recording in the Caribbean, but actively resist it in favour of non-linear storytelling. In visually reappropriating the disorienting chaos and opacity of a hurricane, she highlights the ongoing impacts of the Plantationocene in the longstanding selective telling of Caribbean histories, while activating the naturally layered diversity of the islands’ ecologies and expanding natural histories through filmic processes to exceed it.

In contemporary art practices, hurricanes disrupt manicured (tourist-centered) Caribbean visual culture both practically and emotionally. By rejecting the aesthetic containment and fantasy of paradise imagery, storms offer a means for artists to engage with rupture and the politics of disaster and reality. As Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation suggests, opacity and errantry are essential tools for resisting the rigidity of identity and transparency demanded by colonial order to reimagine the Caribbean. Opacity asserts the right to remain irreducible to Western frameworks, while errantry embraces movement, unpredictability and relational identity beyond rigid borders. For moving image works, given the added complexities of time and movement, the dynamism of these storms offers a means to expand this work beyond light and material into a temporal and even a spatial dimension. Hurricanes here can present a new aesthetic framework, a tempest aesthetics: tools for dismantling colonial visual languages, fostering new ways of seeing and understanding the region’s histories and ecologies.

Within this framework, hurricanes emerge as a powerful narrative device in Caribbean moving image art, transforming the enduring horrors of these storms into aesthetic agents against colonial sanitisation and silencing. These storms expose the politics of erasure often imposed on the Caribbean, a region historically silenced and dismissed as distant and peripheral, on the margins, perpetuating cycles of neglect and vulnerability. The increasing intensity and devastation of recent hurricanes lay bare the enduring legacies of colonialism while confronting the contemporary structures that maintain these inequities. The irony is palpable: the Caribbean, least responsible for climate change, suffers its most devastating consequences, as Hurricane Beryl’s 2024 destruction proved during a record-breaking season. Hurricanes also reveal how global responses to the climate crisis mirror the aesthetics of colonialism, described succinctly by Glissant as ‘reactionary or sterile’.[6]

While methodologies of the artists differ between materiality and aesthetics, hurricanes serve both creatives as a compelling lens through which to interpret these works in their embodiment of errantry and opacity, resistance and refusal. Muriente engages with material impermanence in colonial readings of Puerto Rico, while Strickland employs digital layering and framing to intertwine histories of cotton with compelling and empowering narratives of resistance. Despite their differences, both remain deeply attuned to the cyclical nature of Caribbean time and embrace nonlinear storytelling. As chaos theory suggests, nonlinear repetition and shifting spatio-temporal scales hold together the paradox of order and disorder, much like the spiralling force of a hurricane. By accessing the chaos, errantry, and cyclical nature of hurricanes, both artists transform their destructive power and lasting impact into tools for reimagining the Caribbean and fostering new, more equitable narratives. They challenge the detached, touristic gaze by confronting viewers with the trauma, loss, and ecological impacts of the Plantationocene, destabilising the visual and psychological comforts of paradise as an artistic or cultural construct. In this way, hurricanes can operate not only as meteorological phenomena but also as decolonial forces. They conceptually contain the potential to unsettle imposed colonial visual languages and historical narratives to generate new knowledge through destruction, reformation, and the perpetual undoing of believed assumptions.

[1] The enduring myth of the Caribbean as ‘paradise’ is deeply rooted in colonial imagination. As Polly Pattullo notes, “whatever the brutality of its history, [the Caribbean] kept its reputation as a Garden of Eden before the Fall.” She further explains that the idea of the tropical island became a seductive image: “small, a ‘jewel’ in the necklace chain, far from centres of industry and pollution, a simple place, straight out of Robinson Crusoe.” This constructed paradise extends beyond the natural environments of the Caribbean, as people themselves are also expected to conform to its stereotypes. (Pattullo, Last Resorts)

[2] An alternative, or supplement, to the Anthropocene, the Plantationocene explains the ways in which the legacies of plantation systems, namely colonialism and capitalism, continue to inform and impact environments and societies.

[3] This materialism refers to the way history in the Caribbean emerges through the dialectical relationship between nature and culture. As Christopher Hitchcock writes in Antillanitė and the Art of Resistance, this history is inherently materialist due to the specificity of this relationship, where Caribbean landscape and memory are deeply intertwined. (Hitchcock, Antillanité and the Art of Resistance).

[4] NALAC, “Sofía Gallisá Muriente,” December 15, 2018, https://www.nalac.org/members/sofia-gallisa-muriente/.

[5] The concept of Caribbean time is often understood as cyclical and nonlinear, resisting Western chronological frameworks and instead unfolding through cycles of rupture and recurrence. This cyclical temporality, marked by fragmentation and simultaneity, reflects what has been described by Alain Baudot as “history in layers,” where past and present coexist rather than follow a strict chronological sequence. Baudot and Holder, Edouard Glissant: A Poet in Search of His Landscape (‘for What the Tree Tells’).

[6] Glissant, Poetics of Relation

Baudot, Alain, and Marianne R. Holder. “Edouard Glissant: A Poet in Search of His Landscape (‘For What the Tree Tells’).” World Literature Today 63, no. 4 (1989): 583–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/40145547.

Glissant, Édouard. Poetics of Relation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2009.

Hitchcock, Peter. “Antillanité and the Art of Resistance.” Research in African Literatures 27, no. 2 (1996): 33–50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3820159.

Murray-Román, Jeannine. “Rereading the Diminutive: Caribbean Chaos Theory in Antonio Benítez-Rojo, Edouard Glissant, and Wilson Harris.” Small Axe 19, no. 1 (2015): 20–36. https://doi.org/10.1215/07990537-2873323.

NALAC. “Sofía Gallisá Muriente.” December 15, 2018. https://www.nalac.org/members/sofia-gallisa-muriente/.

Pattullo, Polly. Last Resorts. Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers, 1996.