Over the past few years, more and more of us have spent a lot of time in our cars, experiencing a world that continues to change rapidly. The safety of our cars as a perfectly contained pod, the freedom of at least being able to go on a long drive, the resurrection of drive-ins – being in a car made things feel normal, for a little while. Atlanta is covered in cranes, opaque construction fencing, and even more traffic. The speed in which this change is happening in Atlanta is not unique. All over the country, growth and expansion is accelerated by changing living patterns due to coronavirus restrictions, the rise of a remote workforce, and population fluxes.

In Atlanta, however, the way the city has developed has always been one of erasure and movement. In the post-Olympic era, Atlanta took the subsequent influx of cash to target public housing tracts such as Techwood and Bowen Homes for redevelopment. By 2011, Atlanta had managed to liquidate all of its public housing, with not even the apartments built by beloved architect John Portman left standing.

Losing so much so quickly is disorienting and damaging to the social memory, the social fabric. It isn’t just a loss of a physical place, it’s the lived incidentals around those places, the births, the deaths, the kisses, the tears.

Artist Carley Rickles has been making work around urban memory and disappearance for years. Burnaway approached her based on her social practice work related to I-20, and asked her expand on her artist project, Missing, for our theme Nodes and Networks.

Jasmine Amussen

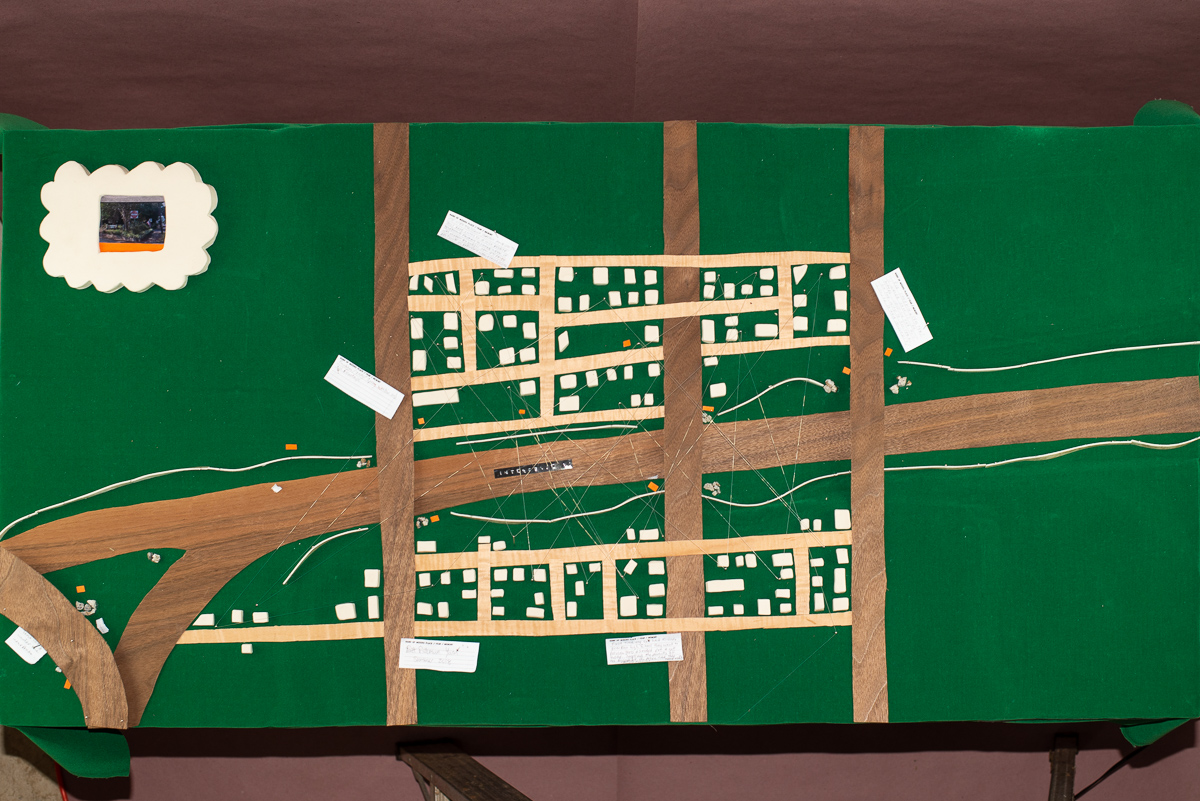

Missing is an open ended social practice and research project which considers displacement, collective and individual perception, visual impacts of time on “place”, and questions the systems which allow a site to “progress” or “decay.” Missing explores if there is an [emotive and/or democratic] action being ignored in the processes of development, which tends to emphasis revenue, and, growth over all else. Missing is an evolution of the field work I began in 2018 during The Residual Spaces Project, which explored the psychogeographic experience and everyday conditions along the street level beyond the walls of I-20. Every Friday morning I walked a different street that dead ended into the interstate dividing neighborhoods and splicing the city.

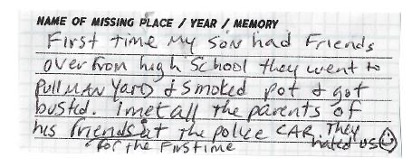

Like I-20 which seems impeded the intimacies of daily life– paradoxically even as it acts as a conduit for movement– I began to think about other erasures enacted in the name of growth and progress. To begin Missing, I created a small participatory model called Porcelain Homes, installed for a brief exhibition at Hi-Lo Press. Visitors were prompted to “Please share the name of a place that is missing, the year you last remembered it, and any memory you have related to it. Then pin it to the model.”

Taking those slips as a guide, I selected some sites to explore further in the hopes of finding evidence of their histories and their geographic locations. I wondered how hints of personal knowledge and interactions might seep through to the sites in their current form. Making a series of small sculptures that explored each place, I blended images from my field studies, research, and Google Earth aerials to interpret the passing of time and how it imprints on genius loci, memory, and the built environment.

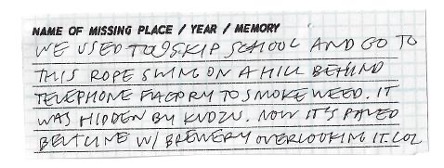

Site 1: The Rope Swing

Participant “A” left a slip about a kudzu laden rope swing, lost now to the steady march of the expanding BeltLine. “A” took me to the swing and told me about growing up near what is now the BeltLine in Old Fourth Ward. The tree where the swing once hung remained on a small wedge of a hill cut, away on both sides by silt fencing. The mound of leftover earth was eroded on one side more than “A” had remembered.

From where we stood by the tree, we could see breweries to the east and a large construction site to the west. Caught in a sound trap of steel hammering, loud energetic music, and crickets, we spied a cop on the BeltLine from our perch on a fifteen foot rise concealed by shrubs. I am not sure we were doing anything wrong, but in the spirit of the place we hid and didn’t speak. He slowly walked by sipping out of a straw, his view remaining at a natural eye level. A pointed to a silver tag on the tree that once held the rope swing; it read “420.”

Site 2: Pullman Yards

Pullman Yards, another site from a slip, now hosts the endlessly popular Van Gogh Experience. Like many changing cities, Atlanta’s industrial spaces fuel an economic interest in the refurbishment of abandoned landscape as an indicator of “hip” neighborhoods.

Hover captions explore my thoughts and feels as I moved between memory and the present at Pullman Yards:

- Van Gogh employees are wearing uniforms – black t-shirts that read “PULLMAN.” Branded in a font that evokes a historical context. Choosing uniforms for employees is an interesting choice. It seems to objectify labor and bodies. I imagine uniforms were worn by the original employees too. Reminds me of the history of contentious labor at Pullman Yards Sites. It was written that Pullman employed more African Americans than others at the time, but treatment was questionable. Knowing this about its history makes the uniform ‘evoking a historical context’ an odd choice.

- Van Gogh employees are wearing uniforms – black t-shirts that read “PULLMAN.” Branded in a font that evokes a historical context. Choosing uniforms for employees is an interesting choice. It seems to objectify labor and bodies. I imagine uniforms were worn by the original employees too. Reminds me of the history of contentious labor at Pullman Yards Sites. It was written that Pullman employed more African Americans than others at the time, but treatment was questionable. Knowing this about its history makes the uniform ‘evoking a historical context’ an odd choice.

There are food trucks here. I am drinking a frozen mango margarita. I wonder if this site of my leisure contained leisure before (Ah, brain freeze) of struggle. What has happened here before?

There are food trucks here. I am drinking a frozen mango margarita. I wonder if this site of my leisure contained leisure before (Ah, brain freeze) of struggle. What has happened here before?

Usually I don’t research a place before field work, this time I did. I recognize the form, or the section of the brick Pullman building the most. The doors are new. I will not be attending the Van Gogh Experience, but one time I did go inside the building. It was for the OVER/UNDER exhibition of the late Harrison Keys (TOES) work put on by Dashboard. At that time TOES was written on the building, I wonder if the tag is still here. For the show there was a 1:1 scale model of Elmyr. I also remember a loud dramatic light and sound show.

Usually I don’t research a place before field work, this time I did. I recognize the form, or the section of the brick Pullman building the most. The doors are new. I will not be attending the Van Gogh Experience, but one time I did go inside the building. It was for the OVER/UNDER exhibition of the late Harrison Keys (TOES) work put on by Dashboard. At that time TOES was written on the building, I wonder if the tag is still here. For the show there was a 1:1 scale model of Elmyr. I also remember a loud dramatic light and sound show.

- To the southeast I can see new and under construction condos through a hanger-type space. The hanger-type space looks newer than the brick buildings. It has a sharp line between the painted white top and gray bottom. In it looks like an old train with lights and an age recognition reading “1927.” Lights hanging from the ceiling, it’s a gimmick.

- To the southeast I can see new and under construction condos through a hanger-type space. The hanger-type space looks newer than the brick buildings. It has a sharp line between the painted white top and gray bottom. In it looks like an old train with lights and an age recognition reading “1927.” Lights hanging from the ceiling, it’s a gimmick.

- It feels like guilt. Likely acknowledging the Pullman Train History through an actual train makes one feel better and justified about the square contemporary looking condos in the background. Maybe that is why I make art documenting change – so I can feel better about contributing to it. “Beer and Cocktails” → “Ice Cold Beers” → “Card, Cash” → “Mango” → “1927”.

- It feels like guilt. Likely acknowledging the Pullman Train History through an actual train makes one feel better and justified about the square contemporary looking condos in the background. Maybe that is why I make art documenting change – so I can feel better about contributing to it. “Beer and Cocktails” → “Ice Cold Beers” → “Card, Cash” → “Mango” → “1927”.

Site 3: Rio Shopping Center / Publix on Piedmont

The former Rio Shopping Center is by far the most unrecognizable of all Missing places I studied. Long gone and replaced by a Publix, it’s current design recalls suburban shopping centers of the early 2000s, despite its location in Midtown. In contrast to the site’s current layout, which includes a parking lot facing Piedmont, the Rio Shopping Center use to engaged the street with a view of its geodesic dome, grid of golden frogs, and red catwalks, parking behind the building. In a 2014 lecture at Georgia Tech Martha Schwartz shares how the frogs were a last stitch effort to add an emotive quality to the otherwise stagnant two foot deep reflection pool. All 350 frogs came from a garden store in Atlanta.

I read in the 1999 Atlanta Business Chronicle article, Rio’s Out; site to become home to mixed-use center, that the beloved, almost mythological gold frogs from the fountain were promised to stay on site. Sembler’s then president of development, Jeff Fuqua (who has since broken off from Sembler Co and formed Fuqua Development) is quoted in the article saying “The critters will be used to line the sidewalks at the new development, which should be complete by the end of 2000.” I found no evidence of their whereabouts after this article. I observed the Publix on Piedmont from the view of my car searching for clues that the Rio Shopping Center existed here. I imagine the gold frogs resting upon the painted lines of the parking lot. The cross walks as raised black and white paths hovering over the reflection pool. The color red appears in cautionary signage which I interpret as a nod to the red railings and seating of the Rio Mall.

Vague accountability and ownership keeps them self-operating off the grid inside the grid. Social accountability is lost in these spaces, along with code compliance.

Vague accountability and ownership keeps them self-operating off the grid inside the grid. Social accountability is lost in these spaces, along with code compliance.

Found items [at these Missing sites] include informal shelters, clothing, abandoned building inventories, and children’s toys are left to collect along the fringes of the city, waiting to be discovered by rare inhabitants.

This essay is part of Burnaway’s yearlong series on Nodes and Networks.

Find out more about the three themes guiding the magazine’s publishing activities for the remainder of 2021 here.