When he began pursuing art seriously while living in suburban Virginia, Taylor Anton White kept his studio in his family’s laundry room in the basement of their house. Although he has since relocated to Richmond and now works in a dedicated studio space, his paintings—which boldly integrate text and found materials and uninhibited abstraction—retain the qualities of something you might discover in a musty suburban basement: simultaneously familiar and mysterious, strange yet endearing, like blurry images of a half-forgotten childhood memory.

Following solo exhibitions in Richmond, Berlin, and Seoul over the past two years, White is preparing for the opening of his first solo presentation in New York, the cheekily titled Free_Hotdog.pdf, at Monica King Contemporary, which opened in Tribeca last fall. I recently spoke with the artist about his paintings’ spirit of improvisation and humor, how he’s learned from his children’s artwork, and the community of artists he’s found in Richmond. Our conversation took place over the phone in January 2020 and has been edited for publication.

Logan Lockner: One of the things I noticed in the press release for your upcoming show was that you have a background in performance art, and the text indicated that this is partially where your work derives its qualities of spontaneity and humor from. Can you say more about that?

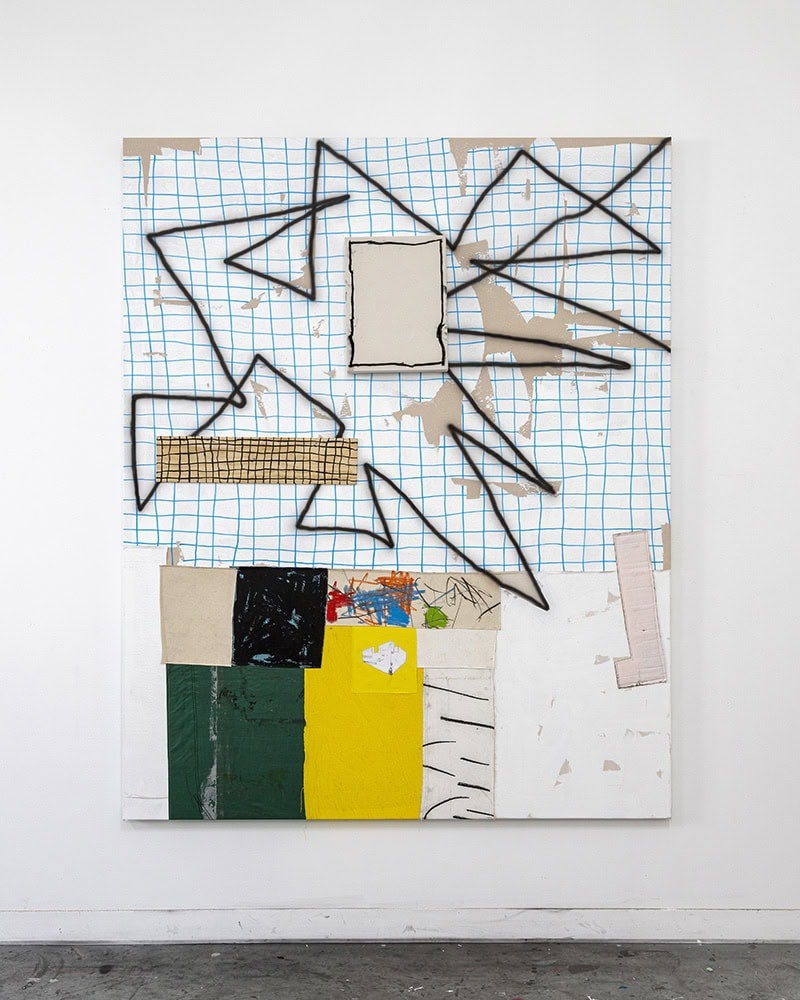

Taylor Anton White: When I went to school, I didn’t know what kind of art I liked. I was like a blank slate, super receptive to anything. I had a great sculpture professor who actually became a serious influence on my paintings. She encouraged me to experiment with performance as an excuse to make a sculpture, an object to interact with. That wasn’t because she was trying to turn me into a performance artist but to show me that you could think about sculpture in different ways, and really just to loosen me up. After doing that and getting comfortable with it and the freedom it gave me, I started making paintings that felt like they had the same amount of speed and dismissiveness as a performance, while also having an eye towards craftsmanship like you might while making a sculpture.

82 by 66 by 3 inches.

LL: Along those lines of craftsmanship, I wanted to ask you about the presence of sewing in your paintings. Do you consider that a subversion of sewing’s traditional feminine associations? How did it emerge as a technique in your practice?

TAW: I had actually never considered the line of thought related to reappropriating a form of women’s work. I’m not using that method of construction because it carries that sort of loaded meaning, but I’m very comfortable with that being read in different ways.

I have a daughter who’s thirteen, and when she was nine or ten, we got her a sewing machine because she wanted to make her own stuffed animals. As is often the case with kids that age, she was trying a lot of new things at the same time, and sometimes her interests would only last a month. At the time, I was kind of connecting modules of paintings together that were disparate things made at different times. I was using adhesives to bond these things together, but some of these super strong adhesives take days to dry. The sewing machine was in my basement, and I realized that if I learned how to use that then I could get the results I wanted immediately. With sewing, I can be impulsive and gestural and get that feeling of velocity and panic out of the machine.

That led to me becoming really obsessed with learning to sew things really strongly, like how a sailmaker would sew something. Eventually I killed several sewing machines and had to get an industrial machine that’s made for sewing leather and stuff like that.

LL: You mentioned your daughter, and I read that you sometimes incorporate your children’s drawings or other artwork into your own.

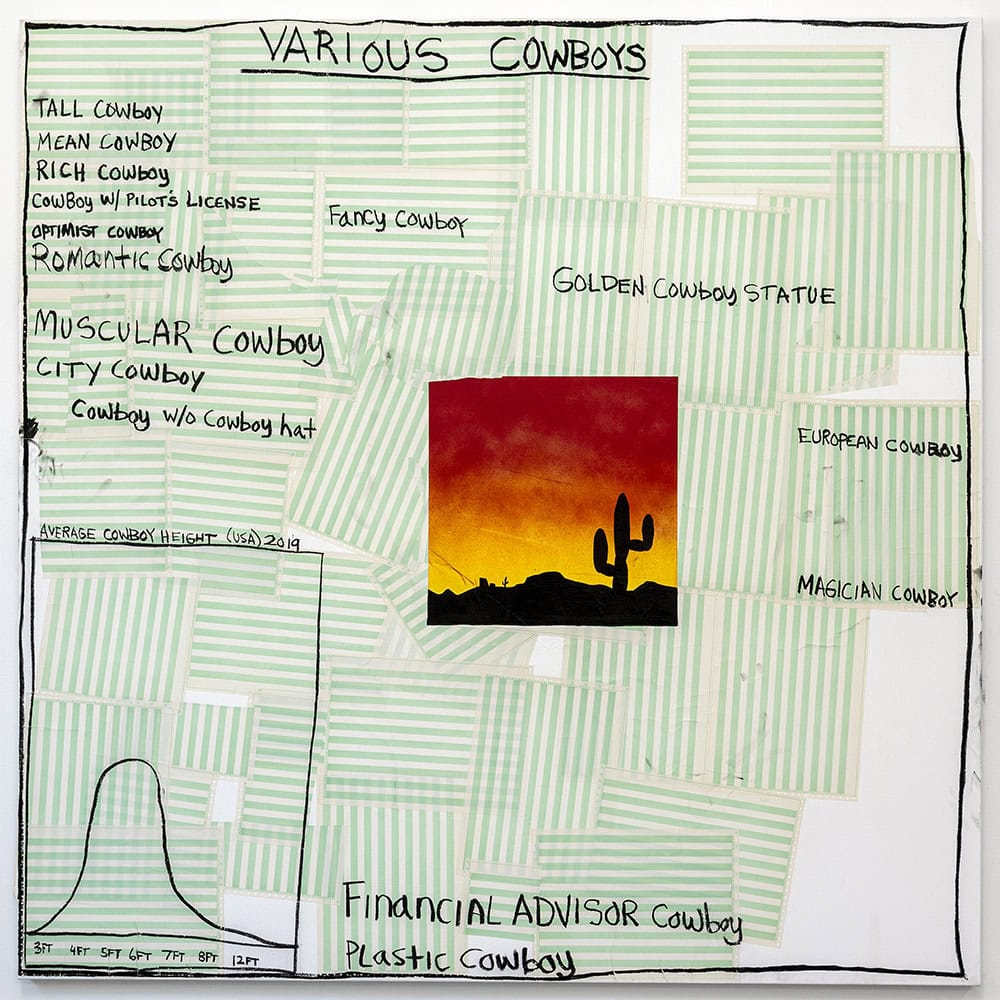

TAW: Yeah, I have two kids: my daughter is thirteen, and my son is nine. They’re both extremely creative kids who are constantly drawing, constantly leaving their drawings and artwork all over the place. I think they’re geniuses, you know, so I want to incorporate what they make, but I don’t directly take their drawings and collage them onto paintings. I’ll take a drawing that one of them makes and try to remember it—not even bring it into the studio—because I’ll never be able to draw it as well as they can. I’m kind of mimicking childishness, but theirs is true. Sometimes they’ll draw something that looks inaccurate or whatever, but that’s not them trying to be abstract: they’re genuinely trying to render something. I look at that and try to hold it in my mind. Maybe even a few weeks later it’ll come out, and it’s been screwed up by memory, and I don’t even remember what the original drawing looked like. That’s how I appropriate what they make but still filter it through myself, so that it gets screwed up by my adult hands.

LL: The title of your new exhibition, Free_Hotdog.pdf, feels like it functions like a lot of your work in that it takes something that might be three-dimensional and concrete, like a hotdog, and then collapses it into something more two-dimensional and abstract, like a PDF. And, of course, within that there’s this sort of formal joke: you can’t eat a PDF of a hotdog, it’s useless. I’m curious about how you arrived at that title.

TAW: A lot of times, titles—especially show titles—come at the last second, after the rest of the work is done. In this case, I was saving something on my computer that was called “Free_Hotdog,” and you know how it asks if you want a JPEG or whatever—I saw the PDF, and I just loved that. I’ve always been interested in the idea that you can make something so unheroic that it somehow comes full circle and becomes heroic-ish.

LL: How has living in Richmond affected your work? How long have you been based there?

TAW: We’ve been in Richmond a little bit over a year, and we really like it. There are a lot of artists here and some good galleries and a great art museum. It’s a place where I can take my kids to the museum and say, “That’s Cy Twombly,” and “There’s Helen Frankenthaler,” and “Here’s Philip Guston.” They get to see these things up close—in the flesh, not just in books—and I think it helps them understand how old this thing their dad does really is.

Taylor Anton White: Free_Hotdog.pdf opens on Friday, January 31 at Monica King Contemporary in New York, where it remains on view through March 14.