Multidisciplinary visual artist Tay Butler is best represented by his studio that serves as an altar to his influences and artistic process: stacks of books on Black military service and political figures, an assembly of Polaroid headshots of community members and visitors to his studio; and countless images and newspaper clippings on sports, Black art, and culture. Using archives of history, pop culture, and collective memory, Butler’s artwork interrogates how the movement of the Black male body has been dually generative and destructive for representations of Blackness. In the most recent chapter of his practice, Butler considered movement through athleticism, commercialization, and the forms of celebrity that emerged alongside basketball’s all-encompassing popularity.

Butler first developed a love for the sport alongside the boys in his community, leading to countless games on the court and endless time spent playing against each other, all of them hoping to be seen as the best. Their reach for excellence was fueled by more than a desire for bragging rights; they shared admiration of the recently-emerged mode of success found in the athlete-turned-stars of the era. From the 1970s to the 1990s, Black athletes became the faces of professional basketball leagues as they increasingly dominated the court and television. As players like Julius Erving, George “The Iceman” Gervin, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Magic Johnson, and Michael Jordan became household names, the sport’s cultural significance grew. Contract values increased and so did opportunities for sponsorships and brand deals. Players’ likenesses sometimes were leveraged to the point of their faces, names, and brand associations being one and the same. Targeted product marketing and portrayals of Black athletes as wealthy, influential, and desirable made them all the more easy for young Black boys to aspire to. Thus emerged an unprecedented level of visibility and with it, the weight of racial representation. Butler’s artistic career began with the search of what lies at the nexus of hypervisibility, culture, and the weight of representation: an inevitable isolation and the obscuring of the self he describes as “hyperinvisibility.”1

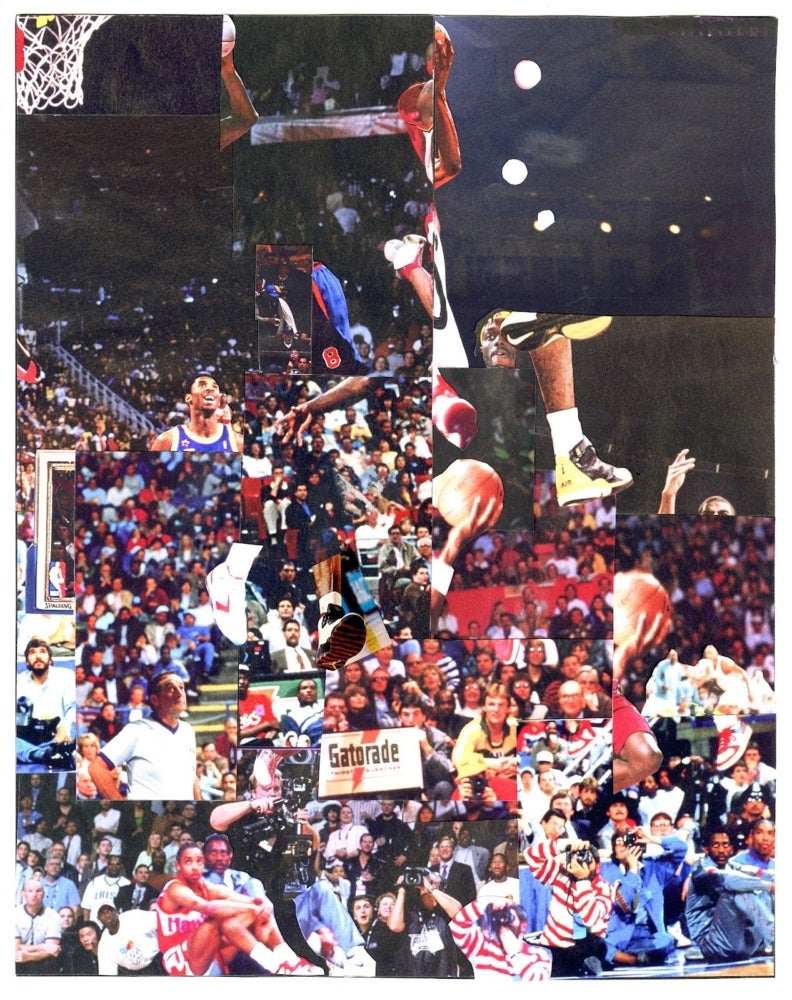

In his collage work on hyperinvisibility, Butler visualizes athletes’ erasure and reduction to the spectacle of their skill. The scenes’ mostly unrecognizable, predominantly white audiences sit in contrast to the proximity of Black faces to the focal point of the image. In one study, Black faces most easy to distinguish are those of other basketball players, either sitting courtside or fragmented up and placed within the assemblage of limbs, hands, and feet that the the space to which the onlookers stare. Even in the absence of the central figures, the awe-struck expressions of fans and courtside athletes alike make it clear that something incredible is taking place.2 Butler considers this absence-awe conjecture as a necessary structure of hyper(in)visibility. “We can watch you play, be great, inspire us on the court. Once you try to fill out or round out your humanity, we stop watching.”3

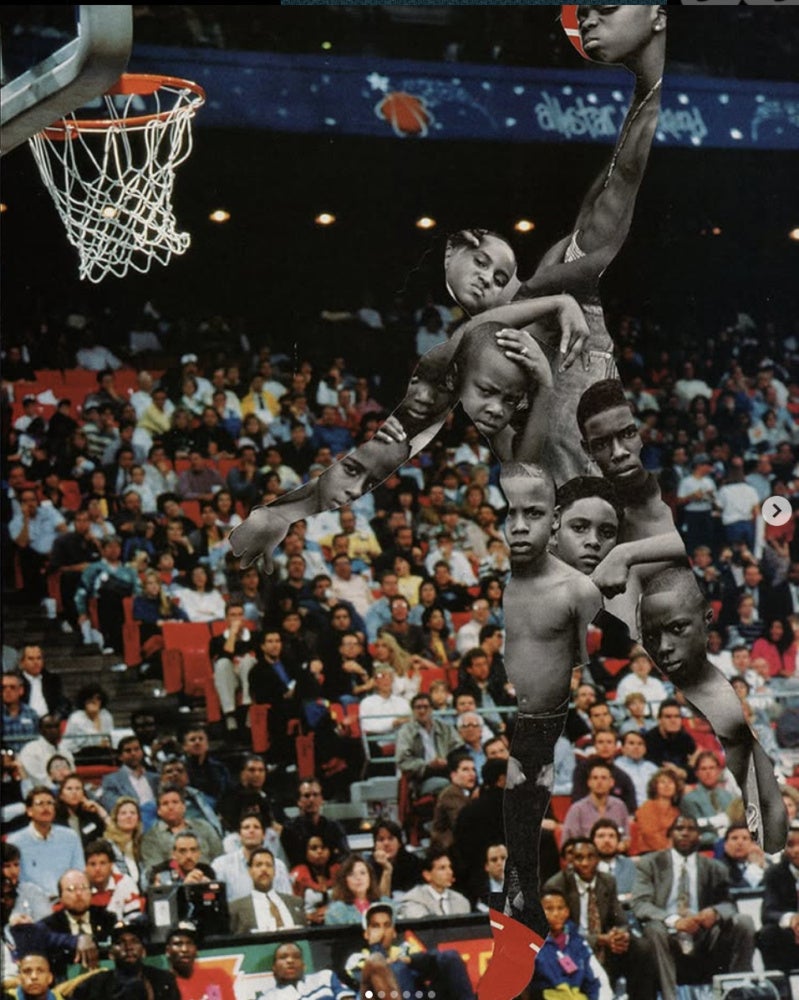

In the same study, where the central players’ identities are made elusive through incomplete forms, they are survived by branding: the colors worn by the players’ teams, the relocation of a Gatorade ad, the logo of Nike’s Air Jordans, and the blurred lettering of an official NBA Spalding basketball. In CONTEST (2023), another collage interrogating hyperinvisibility, a similar crowd focuses on a single de-identified figure instead. Rather than being represented by his branding, the space he held is filled with the portraits of Black boys.

The markers of monetary partnerships exist in conversation with the contrast between the imagery of boys against the sea of white faces, addressing the paradox of belonging and community in Butler’s hyperinvisibility. “You’re literally a beacon of hope to all of these Black people, but you’re not in the community with these Black people,” he explains.4 Time- and location-based demands of athletic careers, historically white leadership and team ownership within the NBA, and the mystifying nature of celebrity have created and upheld a system that isolates athletes from their communities and centralizes wealth in the hands of a small, relatively homogenous group.5 Therefore, Butler argues that the basketball industry’s greater financial ecosystem relies on the commercialization and co-opting of athletes’ likeness and aspirational status to sell products, sustain monetary partnerships, and keep stadiums filled come game time. “You’re just a star for them to stare at. A star in the sky.”6

“It applies to movie stars, rappers, artists, politicians too…These figures will craft legacies for themselves, but they’re confiscated from them to further power…In focusing too much on the confiscated, altered forms of these legacies, we lose sight of our values.”7 To resist the centralizing of power, disenfranchisement, and the co-opting of identity for capitalist gain, Butler finds it necessary to educate others on these realities through art-making and the reclaiming of these stolen legacies. In the next chapter of his artistic career, he seeks to reclaim a legacy of his own.

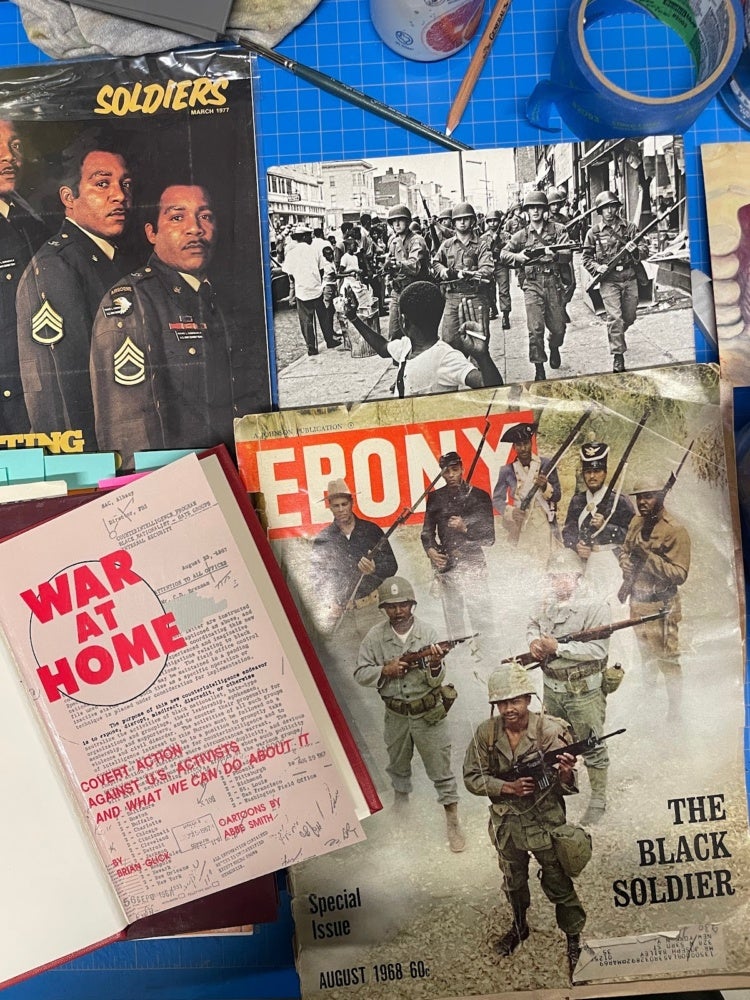

Immediately after high school, Butler served in the military for twenty-one years, retiring as a staff sergeant before transitioning to a career in engineering and later becoming a professional artist. In his interrogation of Black men’s movement through the lens of basketball, he found himself returning to the greater theme of Black men’s movement and labor in the United States. In particular, the means through which systems of violence and oppression are upheld by the exploitation of narratives surrounding Black men’s bodies, labor, and identities.

As a retired veteran, Butler’s relationship with these themes is complex. Engaging these aspects of his identity led him to reflect on the history of Black servicemen in the United States and the notion of what it means to be “at war,” whether on the battlefield abroad or in resisting oppression in one’s own country. Inspired by George Jackson’s Blood in My Eye, Butler began to wonder why more Black people didn’t consider themselves to be in a battle against the US government, considering its targeting of “insurgent” Black groups, such as the FBI’s Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO), known for targeting Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and the Black Panther Party.9 Now, Butler seeks to disrupt the narrative of Black soldiers as non-resistant and allegiant to imperialist efforts abroad. He considers this new artistic chapter to be meaningful, necessary, and timely in the current sociopolitical climate. “Things are looking bleak,” he regards.“The only way out of things is a new consciousness, a new organization.” For Butler, looks like pushing his artistic practice to new narrative horizons, standing firmly on his beliefs, and encouraging others to do the same through reading groups and educational workshops. “I’mma do my part or die trying. It’s all I can do.”10

1] Tay Butler artist statement. A Friendly Game of Basketball. Lawdale Art Center, Houston, TX. April 18 – May 18, 2024. https://lawndaleartcenter.org/exhibition/tay-butler-2/.

2] Gillespie, Blake. (2023, April 11) Multi-disciplinary artist Tay Butler on “Hyperinvisibility” Sacred Hoops Book. https://sacredhoopsbook.com/playbook/tay-butler-on-hyperinvisibility.

3] Gillespie, Blake. (2023, April 11) Multi-disciplinary artist Tay Butler on “Hyperinvisibility” Sacred Hoops Book. https://sacredhoopsbook.com/playbook/tay-butler-on-hyperinvisibility

4] Tay Butler in conversation with author, July 2025.

5] Richard E. Lapchick, et al. “The 2023 Racial and Gender Report Card: National Basketball Association”. The Institute for Diversity and Ethics In Sport. https://www.tidesport.org/_files/ugd/c01324_abb94cf8275d49499e89fa14f0777901.pdf.

6] Tay Butler in conversation with author, July 2025.

7] Tay Butler in conversation with author, July 2025.

8] Tay Butler in conversation with author, July 2025.

9] Federal Bureau of Investigation, “FBI Records: The Vault — Black Extremists.” FBI Records: The Vault, Federal Bureau of Investigation, vault.fbi.gov/cointel-pro/cointel-pro-black-extremists.

10] Tay Butler in conversation with author, July 2025.