In our feature Take Five, Burnaway highlights five artists we’re excited about who are working in the South or are from the region. The second edition of this series focuses on artists working in a medium with strong historical and material ties to Southern culture and craft: textiles. From the generations-long tradition of quiltmaking in Gee’s Bend, Alabama, to the contributions of indigenous and South American people to textile design, textiles have long been associated with gendered forms of so-called “women’s work” and folk traditions—an interpretative gesture that has often worked to exclude such artworks from the realms of museums and galleries. Contemporary Southern artists draw upon and recontextualize these complicated histories while also incorporating the influences of photography, abstract painting, and sculpture into their quilts and other textile works.

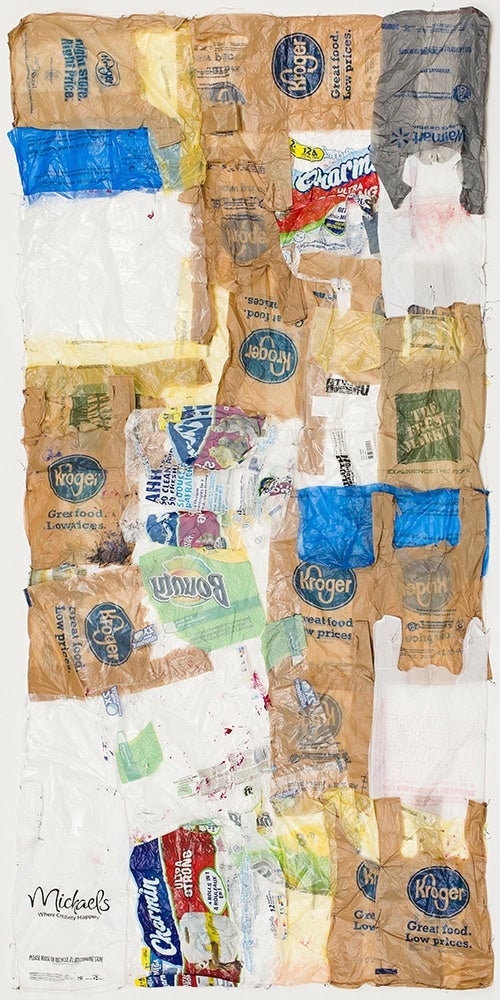

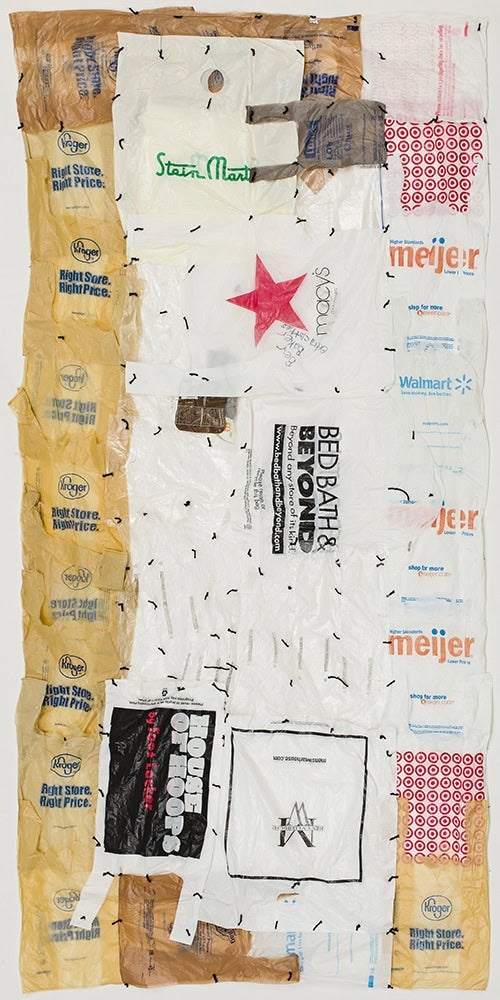

Coulter Fussell

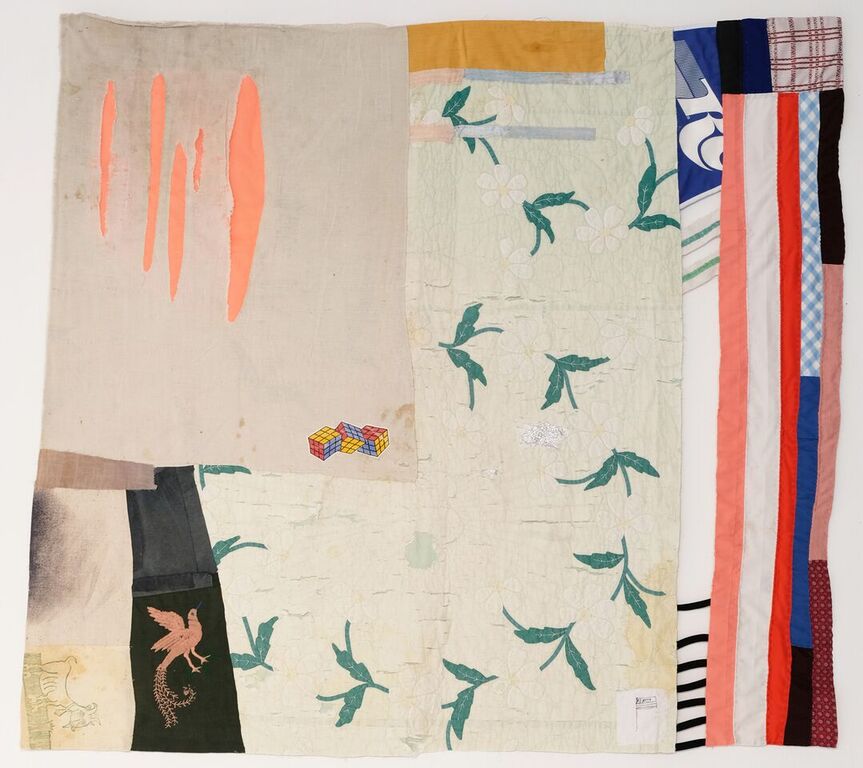

Born and raised in the textile town of Columbus, Georgia, artist Coulter Fussell attributes her approach to artmaking to the dual influences of her mother, a lifelong quilter, and her father, who worked as a museum curator throughout her childhood. Incorporating appropriated graphic elements amid abstract compositions, Fussell employs a visual language that owes as much to contemporary painting as it does quilt-making conventions. While working as a server in Oxford, Mississippi—a job she’s held for most of her life—Fussell also operates her studio and a store, Yalorun Textiles, in the nearby town of Water Valley. A 2019 United States Artists fellow, Fussell is set to open at a solo exhibition, The Raw Materials of Escape, at the Halsey Institute for Contemporary Art in Charleston, South Carolina, in early 2020.

— Logan Lockner

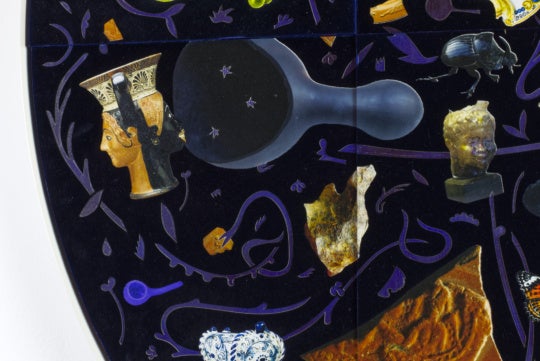

Martha Clippinger

Textile artist Martha Clippinger—who, like Fussell, grew up in Columbus, Georgia—has followed the precedent set by Anni Albers by boldly incorporating influences from Mexico in her work. Obsessive about the power and presence of color, she embraces the bright fury of traditional styles from Oaxaca, Mexico. Spending periods of time in Oaxaca off and on since earning her MFA from Fordham University in 2008, she decided to learn Zapotec, the indigenous language spoken in Oaxaca. Because she was able to speak the regional dialect of Zapotec with local weavers and artisans, she became close friends with a married couple, Agustín Contreras Lopez and Licha Gonzalez Ruíz, with whom she formed a creative partnership. In 2017, they produced the textile works Clipppinger exhibited at Institute 193. Aside from textiles, Clippinger works with wood and acrylic paint to make forms and figures that speak softly in concert with her woven works.

— Jasmine Amussen

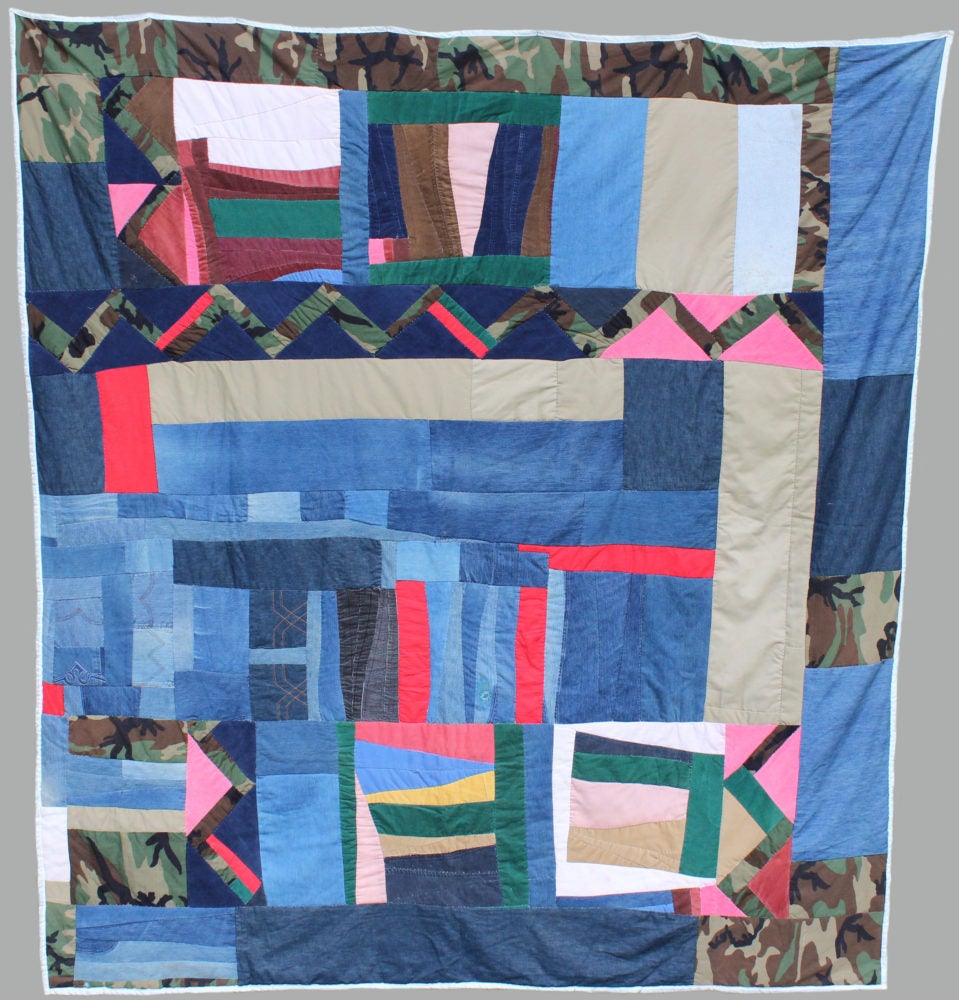

Mary Lee Bendolph

A lifelong resident of Gee’s Bend, Alabama, Mary Lee Bendolph began quilting with her mother Aolar at the age of 12. People outside of the Gee’s Bend community would call her quilts “crazy quilts” because they are made with no discernible, strict pattern. Compared to her other female relatives, many of whom are members of Gee’s Bend’s quilting community, Bendolph says she worked quickly, as is apparent in her dynamic shapes and geometric compositions filled with frenetic energy and color. An exhibition of Bendolph’s quilts, Quilted Memories, opens at the Georgia Museum of Art in Athens in October. A quilting workshop with Bendolph is set to take place at 11 am on October 4, with a film screening and panel discussion featuring quilters from Gee’s Bend at 3:30 pm, to be followed by the exhibition’s opening reception.

— Jasmine Amussen

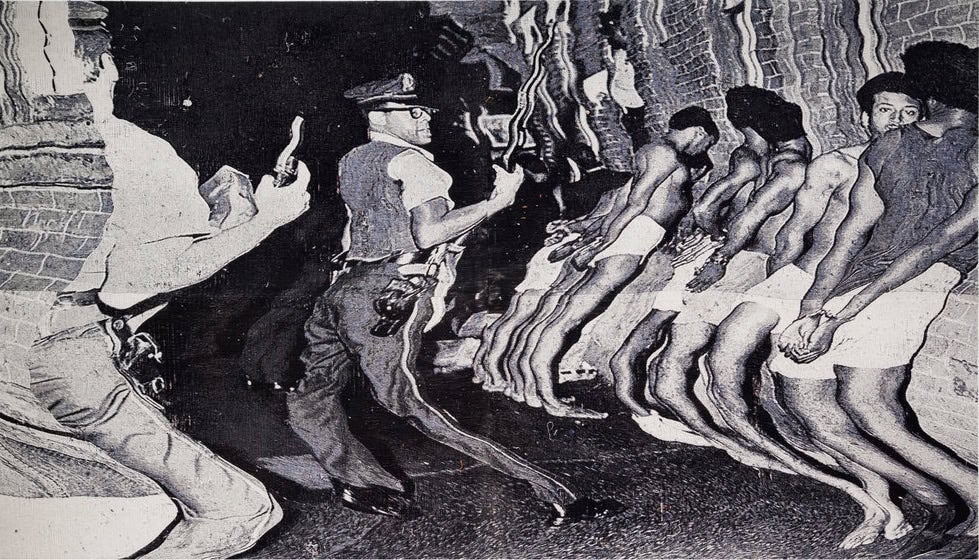

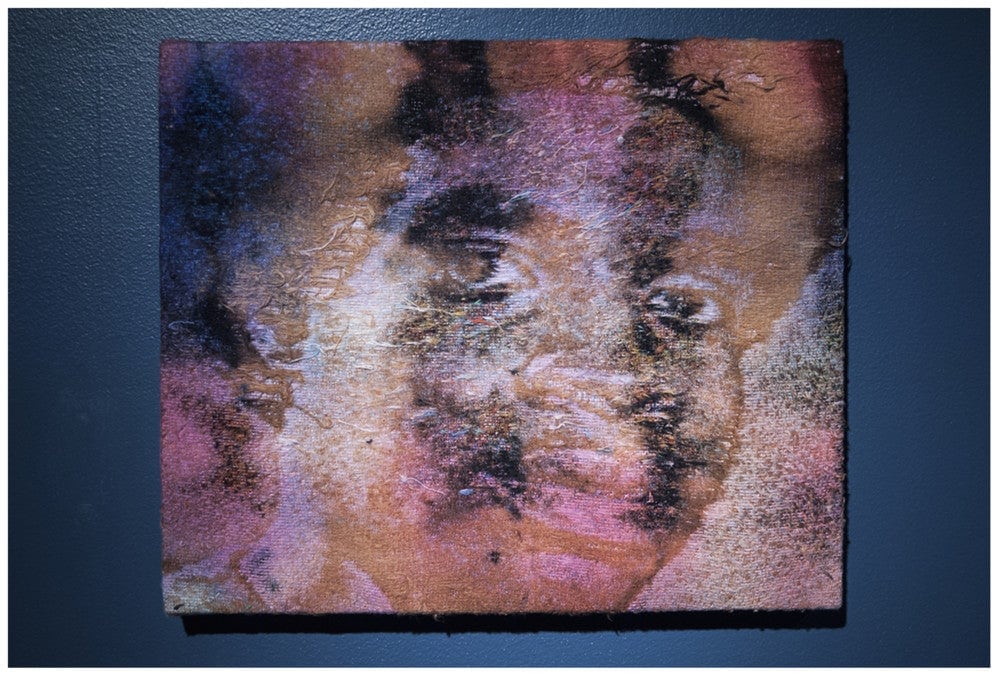

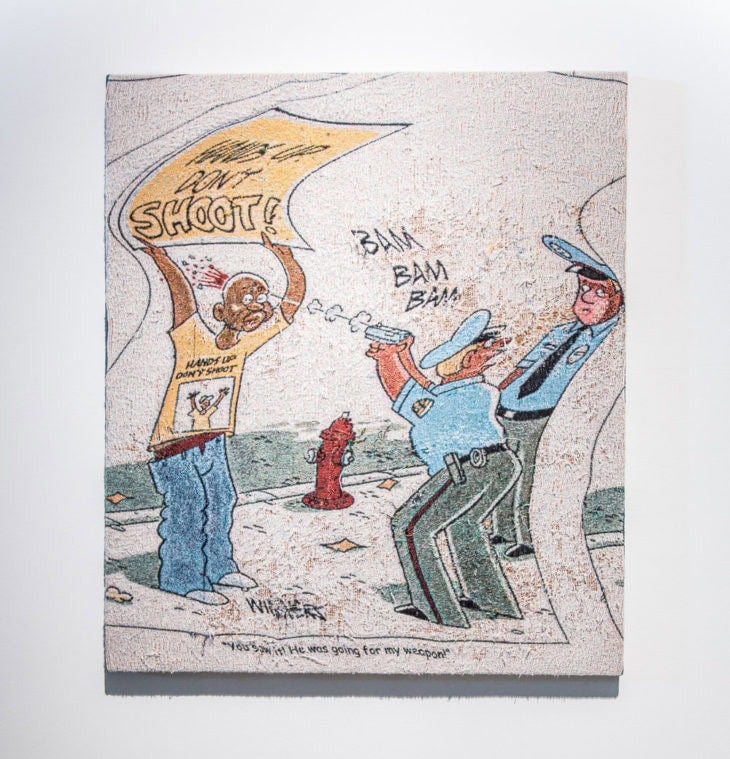

Noel W. Anderson

Louisville native Noel W. Anderson has spoken about his use of textiles (and particularly cotton) as a deliberate material gesture meant to both reflect and interrogate his identity as an African American man. Anderson describes the Jacquard tapestries in his solo exhibition Blak Origin Moment as merging “painting, photography, print, and weaving into one synthesized event.” Anderson investigates topics including police violence against Black men and the conviction of Brock Turner, a Stanford student infamously convicted of felony sexual assault, by distorting found images from archival and contemporary sources in fraying tapestries. After debuting at Cincinnati’s Contemporary Art Center in 2017, Anderson’s Blak Origin Moment opens at Chattanooga’s Hunter Museum of American Art on October 11.

— Logan Lockner

Jessie Dunahoo

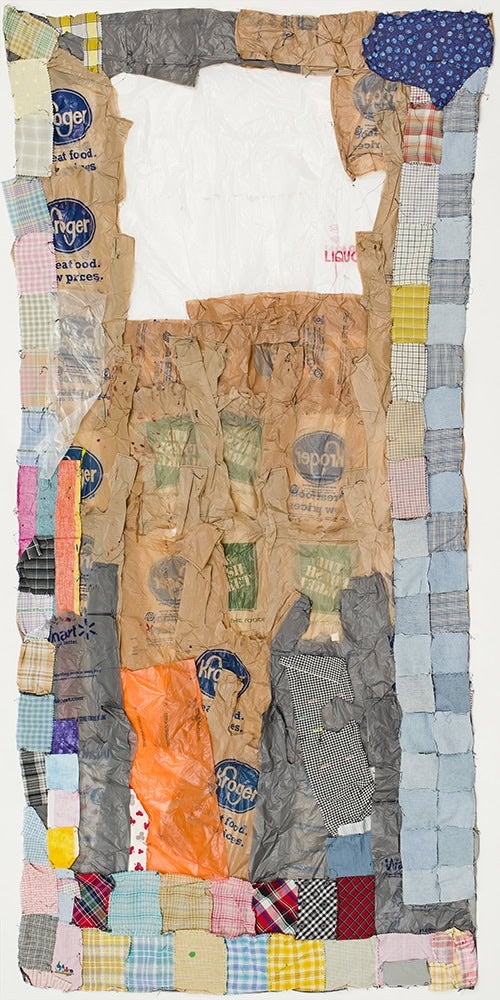

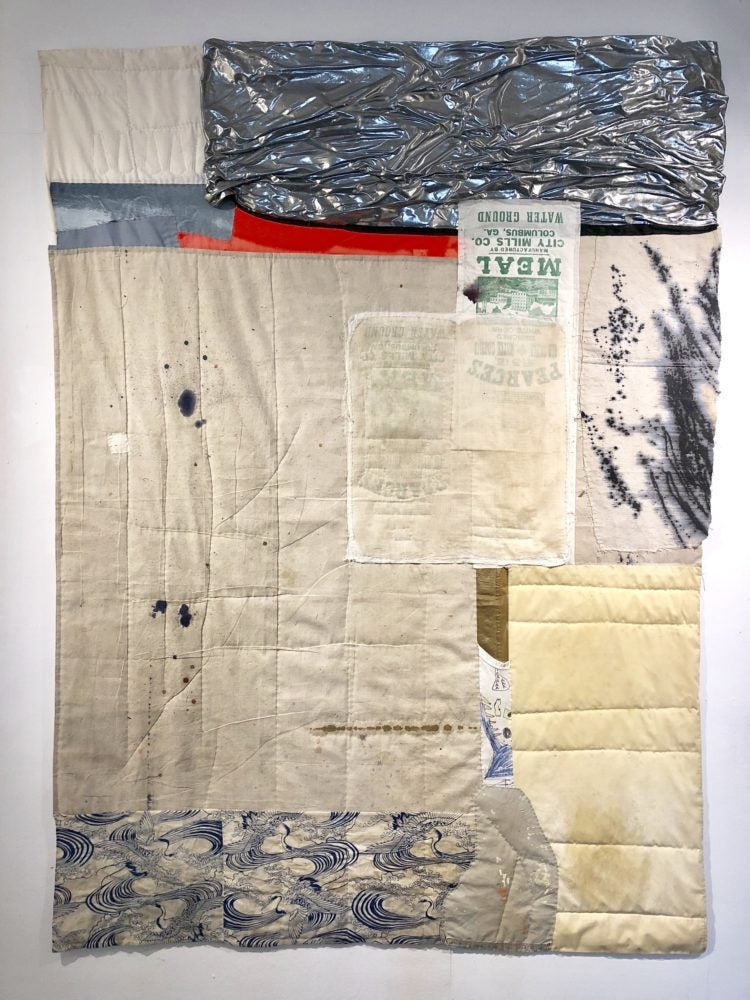

The late Kentucky artist Jesssie Dunahoo, who died in 2017 at the age of 84, spent the majority of his adult life crafting quilt-like works that fit the measurements of the four-by-eight-foot studio table he used at the Latitude Artist Community, a Lexington center focused on working with people who are considered to have disabilities. (Beverly Baker, whose work was featured alongside Dunahoo’s in the 2019 Atlanta Biennial, also works at the center.) Deaf at birth and blind from an early age, Dunahoo first built structures at his family farm that he would use to navigate the environment. Bruce Burris, Latitude’s co-founder, told curator Phillip March Jones that Dunahoo worked “by feel,” organizing his materials according to texture and density. Since his death two years ago, Dunahoo’s work has been presented at the Elaine de Kooning House in East Hampton, New York, and as part of the 2019 Atlanta Biennial, co-curated by Jones.

— Logan Lockner