In our feature Take Five, Burnaway highlights five artists we’re excited about who are working in the South or are from the region. In this edition, we consider artists who are living in or making art about the rural South. Across mediums ranging from sculpture to photography to painting, these artists are confronting ecological damage, poverty, and great beauty from island communities to Appalachia.

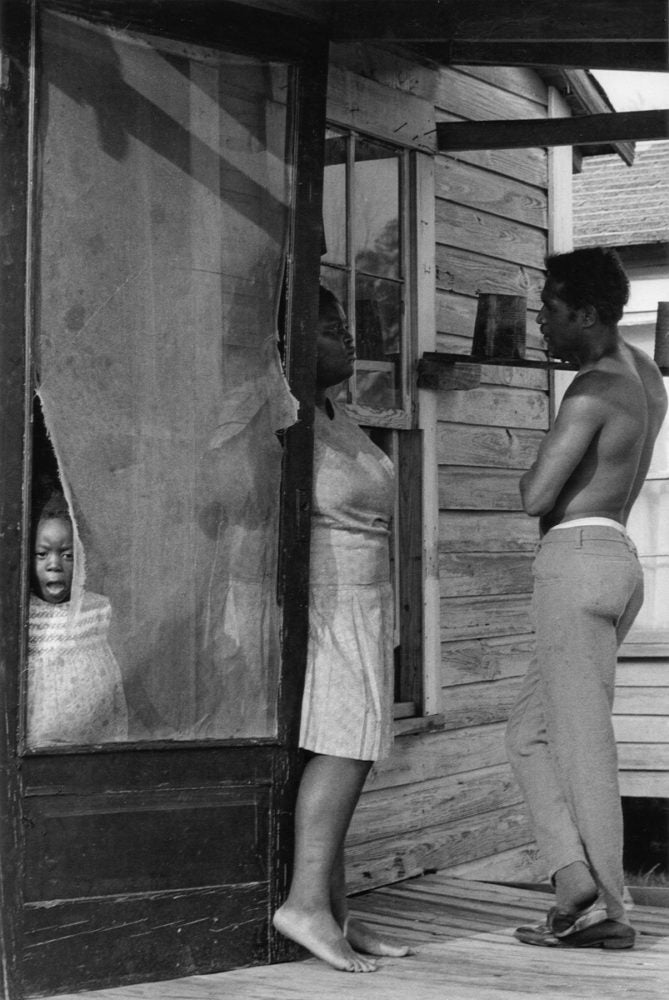

Allison Janae Hamilton

Allison Janae Hamilton uses multi-media installation, photography, and sculpture to unravel our understanding of “Americana” in relation to the landscape of the rural American South. Although currently based in New York, Hamilton was born in Kentucky and grew up in the coastal region of the Florida panhandle, often visiting her family’s homestead in rural West Tennessee. Her works draw from African-American nature writing, folklore, farming and hunting rituals, the Southern gothic, and mysticism as means to address concerns for a landscape plagued by the enduring trauma of racial violence and climate change in the region. Hamilton was a 2018-2019 artist-in-residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem and received a Creative Capital Award in 2019 to create Front Yard, “a land-based project with a twofold focus as a large outdoor sculpture installation with an accompanying cultural and research hub in the artist’s home region of North Florida.”

— Emily Llamazales

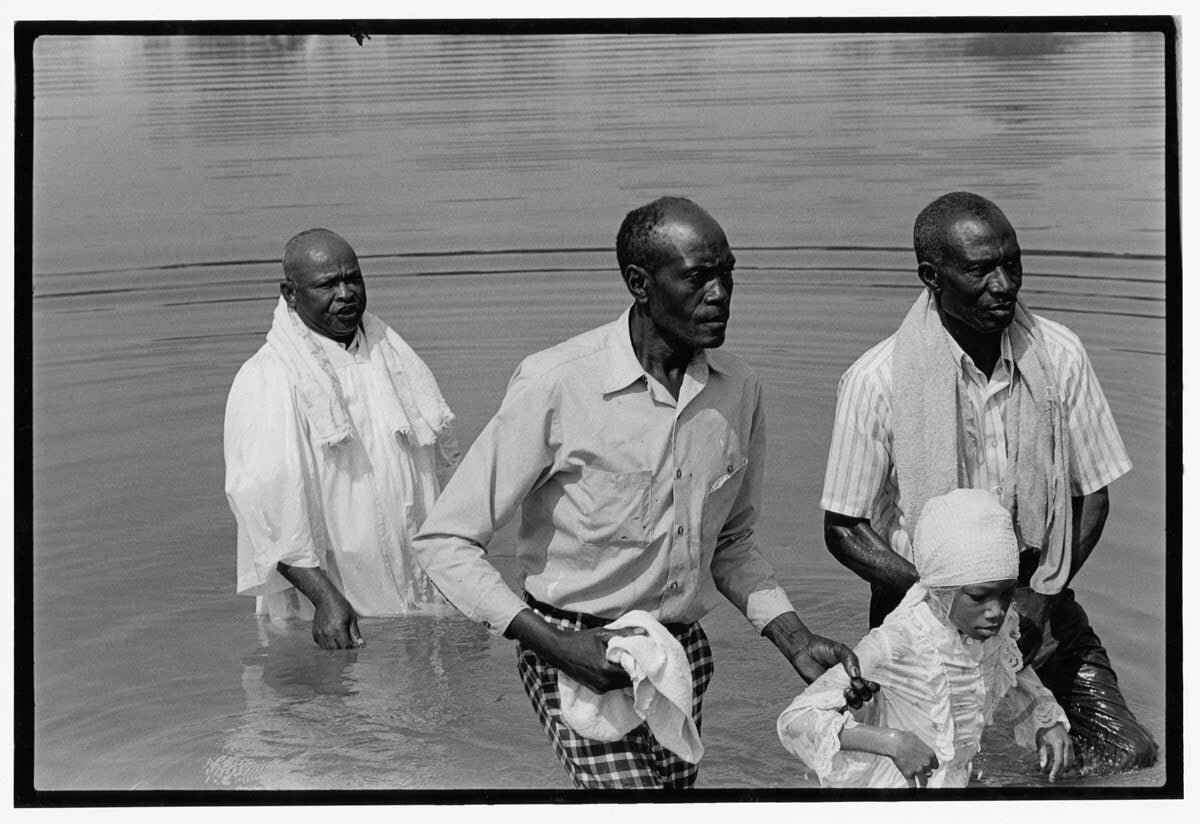

Paul Kwilecki

As a lifelong resident of Bainbridge, Georgia, the late Paul Kwilecki documented the life and work of those in town and the surrounding Decatur County. By the 1960s, Paul had graduated from Emory University and moved back to his hometown, where he began a family and decided to take up his childhood hobby of photography once again. Between 1960 and 2001 Paul’s work reached outside of the small South Georgia town, as he received a grant from the NEA, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and his photographs joined permanent collections at MoMA, the High Museum of Art, and the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University. The county courthouse, agriculture, cemeteries, churches and the Flint River occupy the majority of Kwilecki’s images. “I tried to capture this vitality and durability in the very best light that I could,” he said in an interview in comment upon his many images of tobacco workers. “The message in my work, as it stands, whatever else it is, is compassion.”

— Emily Llamazales

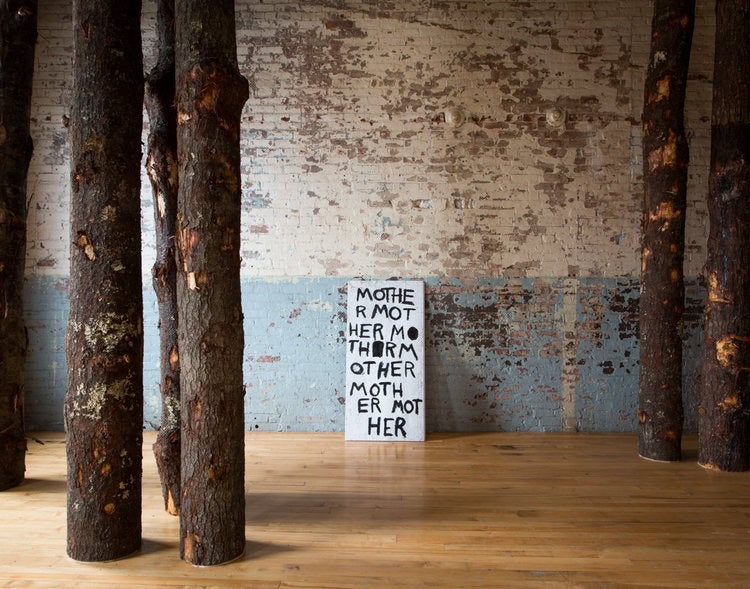

Charles Harlan

After growing up in Smyrna, Georgia, and spending a decade living and working as an artist in New York, Charles Harlan recently relocated to rural Newport, Virginia. In Mountain Lake, his solo exhibition at JTT in New York late last year, Harlan responded to feeling “like an archeologist cataloguing some ancient civilization” while exploring the surroundings of the decades-old farmhouse where he now lives. Harlan’s work has long been concerned with ideas often associated with ancient civilizations: simple but powerful tools and structures, esoteric philosophy, the emergence of ritual. By subtly manipulating readymade materials, Harlan invites viewers to reconsider the distinctions between artworks, the built environment, and nature. In another series—a portion of which was presented simply as Trees at Tif Sigfrids in Athens, Georgia, in 2018—Harlan adopts another sort of readymade: the hybrid forms of trees which have grown together with portions of fencing or other materials.

— Logan Lockner

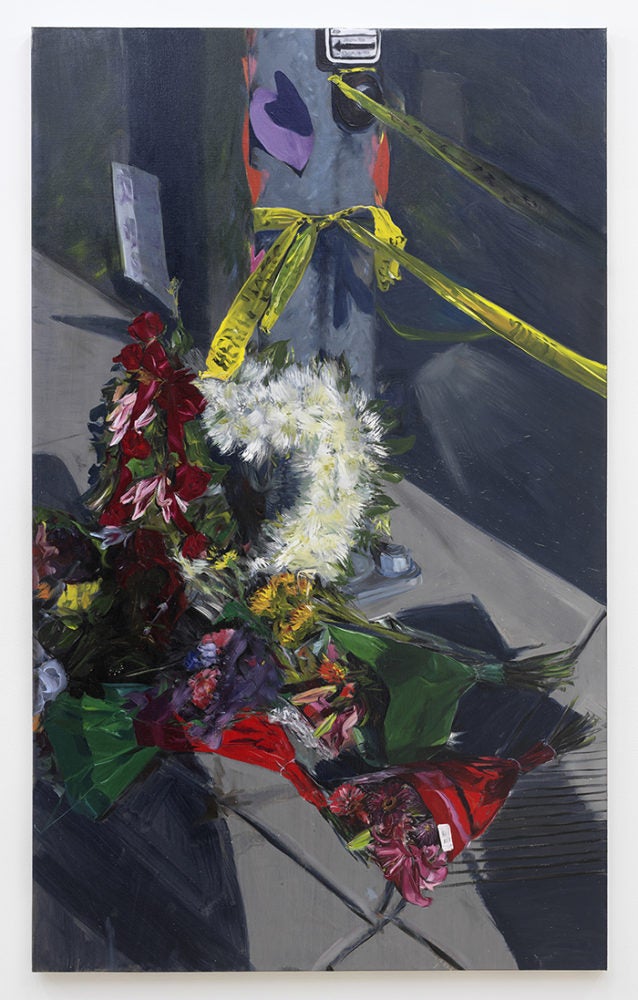

Stacy Kranitz

One part of the difficulty in addressing ‘the rural’ as a whole, as with the South, is that it encompasses so much more than traditional narratives allow. Rural usually conjures images of fields, of the American Midwest, and the Appalachian region. There is a whole swath of rural territory that is oriented around islands, coasts, and waterways. Like their more landlocked counterparts, rural water way communities face environmental distress, poverty, and economic disinvestment. They also hold some of the country’s most precious environmental jewels, delicate ecosystems that protect many life forms and barriers against hurricanes and other storms. Kranitz’s documentary practices finds these images of beauty and terror.

— Jasmine Amussen

Tom Holmes

I grew up in the mountains of East Tennessee among the children of hunters and outdoorsmen, where every day of my primary education at least one child in my classroom wore some form of camouflage attire. We sometimes played a juvenile game—the temptation still crosses my mind—of intentionally bumping into a person wearing camo and exclaiming, “Sorry, I didn’t see you there!” Perhaps it is a cheap laugh, but the mechanics of the joke feel incisive, picking apart at the contradictions that characterize camouflage: visibility and concealment, artifice and authenticity. These paradoxes are contained in the name of one of the most popular brands of camouflage, REALTREE®, which has recently been borrowed by artist Tom Holmes as the title for their fourth solo exhibition at the gallery Bureau in New York. Obviously the clothing and other products manufactured by the camo company REALTREE® are, in the strictest sense, neither real nor trees, but the sense of realness they confer through the social performance of identity is potent, whether in the case of rigid masculinity in the rural South or second-hand trendiness in a Bushwick thrift store. In the press release accompanying the exhibition, Holmes—who has lived in rural Tennessee for the past decade—noted that “[camo] can be used as a kind of cloak of ‘realness’ for precarious radical bodies amidst the conservative norms of the South.”

— Logan Lockner, from “Got to Be REALTREE®: Tom Holmes at Bureau, New York”