I’m not insufferable so I don’t identify as a dandy, but I am a Black man who loves clothing. I might’ve hiked up to the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET) with very low expectations about Superfine: Tailoring Black Style but I ended up on the train back to Brooklyn with the following:

1) A deeper understanding and reverence for the mechanics of Black style.

2) More questions.

3) A list of designers I’ve never heard of to later look up on eBay.

4) A plan for where to rank the exhibition’s catalog on my Christmas list this year.

The annual exhibition of the MET’s Costume Institute, Superfine is based on the research of Monica L. Miller’s 2009 book Slaves to Fashion which details the cultural history and contemporary relevance of the Black dandy across the African and Transatlantic diaspora. Although the exhibition proves that Dandyism has manifestations all across the world, there were several elements tying the show to the American South and Caribbean, such as the inclusion of many designers of Caribbean descent, like Grace Wales Bonner and Maximilian Davis, and various historical elements included in the show that make links to American slavery and Civil Rights activism in the South.

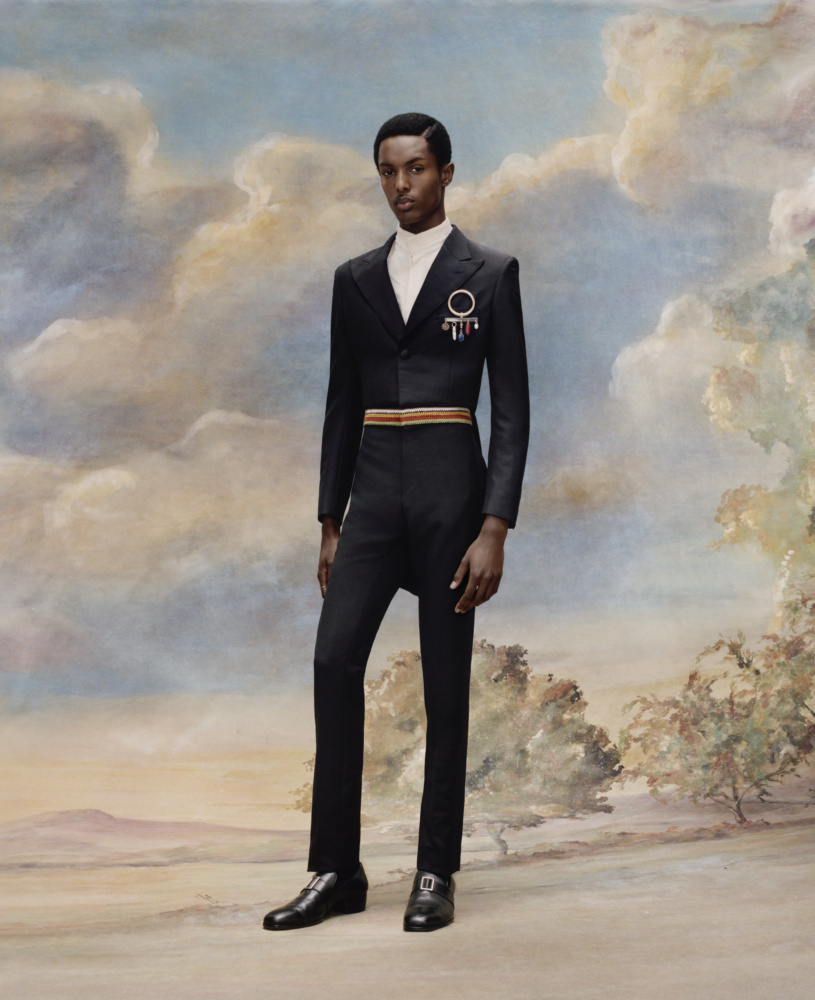

In Superfine, work by well-known contemporary Black designers and brands, like Virgil Abloh (Louis Vuitton, OFF WHITE), Pharrell Williams (Louis Vuitton), Grace Wales Bonner (Wales Bonner), and Maximilian Davis (Ferragamo), is placed alongside emerging and lesser known brands, like 3.PARADIS and L’ENCHANTEUR. Vitrines dedicated to historical figures like Frederick Douglas and W.E.B. Dubois, as well as sections including printed ephemera from pre-Emmancipation, allow the exhibition to deftly argue that “Dandyism” is not a trend or movement but rather a lingering consequence of centuries of African and European entanglement. An overall conceit of the exhibition being that methods of Black dress have shaped and been shaped by the events of global culture in uncountable yet very traceable ways.

Like the pockets of zoot suits, the ideas, paths, and contradictions explored within Superfine are deep, broad, and very unpredictable. The exhibition opens with a section titled Ownership, featuring a brightly colored amethyst livery coat worn by an enslaved servant in seventeenth century Baltimore. The presentation looks across an expanse to a massive monogrammed Louis Vuitton bag designed by Virgil Abloh, covered in vines and appliqued flowers made of cut leather. The two objects being in sight of one another work as if to communicate that very little about Black style and its relationship to excess has ever actually been neutral. Just as current day Louis Vuitton bags are markers of status, even when they’re not carrying a bouquet of calfskin violets, so too at a time was the possession of a living human person. Uncomfortable exchanges between objects like this are a skillful and frightening reminder of America’s once true supermodel: Slavery, whose large and imposing silhouette can be found looming at every corner of the show as it does throughout the nation’s history. If the Dandy is a figure reliant on exuberant displays, often in the hopes of communicating access to wealth, excess and perhaps the world’s finest luxury: safety, it is one that is never without risk or entirely unaware of its surroundings. Within the construct of the Black Dandy is an understanding that relationships between class and commerce, labor and leisure, are deeply and inherently fraught and complex.

Baltimore, Gift of Miss Constance Petre; Right: Livery coat, Brooks Brothers (American, founded 1818), 1856−64; Historic New Orleans Collection, Louisiana in Superfine: Tailoring Black Style at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photograph by and courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Speaking of complications, Superfine is about clothing, but its subtext could very tangibly be migration. Specifically, the show investigates how thoughts, customs, sensibilities and people have traveled around the world with or without their consent. Several designers are working in countries not native to them and several pieces throughout the show feature elements of dress borrowed and reinterpreted from other cultures across the African diaspora. In a 2023 conversation with British GQ, Grace Wales-Bonner has admitted that her own approach to menswear involved wanting “to bring an Afro-Atlantic perspective to European luxury.”[1] The wall labels of the show extensively discuss, not only the designer, but also their origins and how their backgrounds have shaped their approach to traditional European menswear. Take for example an in-process jacket by Andrew M. Ramroop, who immigrated to London from Trinidad and Tobago in the late sixties and went to work on Saville Row as a tailor. The ensembles of the Jamaican Caymanian designer Jawara Alleyne are another example.

Even though the sleek, austere, sexy, and at times, funereal all black exhibition design aided by artist Torkwase Dyson oscillates a little too closely between mausoleum and salesfloor, the MET wastes no time in flexing the full extent of their museological powers by featuring vitrines dedicated to the belongings of Frederick Douglas and W.E.B. DuBois. The musculature does not stop there! Deeper inside are cases of archived, printed media, such as rewards posters for catching runaway enslaved people and pages from periodicals that feature caricatures of vaudeville and blackface. By putting the Black dandy under a microscope, the viewer is able to then examine what taste, survival, and acceptability could have meant throughout time.

Among other things, the Black dandy is a scholar. Their studies are integral to their survival, such as in the case of the enslaved married couple Ellen and William Craft. The two escaped Georgia heavily aided by clothing, with lighter-skinned Ellen posing as an upper class white gentleman, costumed in a way that Southern men traditionally dressed at the time while William posed as her servant. An incredibly real example than an examination and adoption of Dandy style could be as serious as life or death. Exploring this further is an incredible section in the show dedicated to ideas surrounding “Black Ivy,” a movement documented in Jason Jules’ book of the same name, in which several Black artists, academics and revolutionaries consciously adopted Ivy League and “preppie” ways of dress during the Civil Rights movement in order to directly combat and circumvent notions of respectability. In this section, there’s even a portion featuring an HBCU-inspired capsule collection by James M. Jeter, Ralph Polo’s first Black creative director, as he references his time attending Atlanta’s Morehouse College.

Like the pockets of zoot suits, the ideas, paths, and contradictions explored within Superfine are deep, broad, and very unpredictable.

When identity is normally evoked by an institution, more often than not, it can come off as shorthand for significance or virtue. A readily utilized and hollow opportunity for an institution to delineate their beliefs by way of vaguely communicating that they might have a few. Superfine, however, demonstrates an institution willing to investigate what exactly an examination of identity through a material lens could offer. As I’m sure Monica L. Miller must’ve also accomplished in her book, Superfine is able to communicate fashion as a fascinating and useful tool to examine interlocking narratives of global capital as spurred on by humanity’s need to classify, assign, and belong.

The MET’s press release states that dandyism “reflects the ways in which Black people have used dress and fashion to transform their identities, proposing new ways of embodying political and social possibilities.”[2] To its credit, the exhibition explores just that, although I wish it would’ve done so to a different soundtrack. Throughout the exhibition on loop blaring from the speakers is a song by Alice Coltrane that thematically makes very little sense. If for one second the music would’ve stopped, and I was able to appreciate what was in front of me without the constant threat of a transcendental good vibe lurking one harp string away, like the glamorous and resolute mannequins suited in silks, kaftans and patterns from all around the world, I too would’ve been Dandy.

[1] Clark, M. (2023, June 7). The Grand Designs of Grace Wales Bonner. British GQ. https://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/article/grace-wales-bonner-interview-2023

[2] Superfine: Tailoring Black Style (Press Release). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. (n.d.). https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/superfine-tailoring-black-style