This essay is an exploration of contemporary Black Queer and Trans Southern aesthetics amidst an ongoing sense of malaise, backlash, and resistance to the yet-to-fall Plantationocene. It offers a reflective examination of creative endeavors that seek to recreate the maroon space, both during a historic moment of heightened visibility and in the search for communal belonging.

Through a combination of an essay, and photographic images of found plants, family, and landscapes, I trace the narratives of my ancestors, who forcibly toiled the land and crops, becoming stewards in central and southeast Texas immersing themselves in spaces and crevices beyond capture and legibility. This is an essay that resembles something like a hot summer evening on a screened in porch. I listen closely to what the crickets, cicadas, and plants have to say. I create a “call and response” that encapsulates the sonics of Black Southern Life in written form.

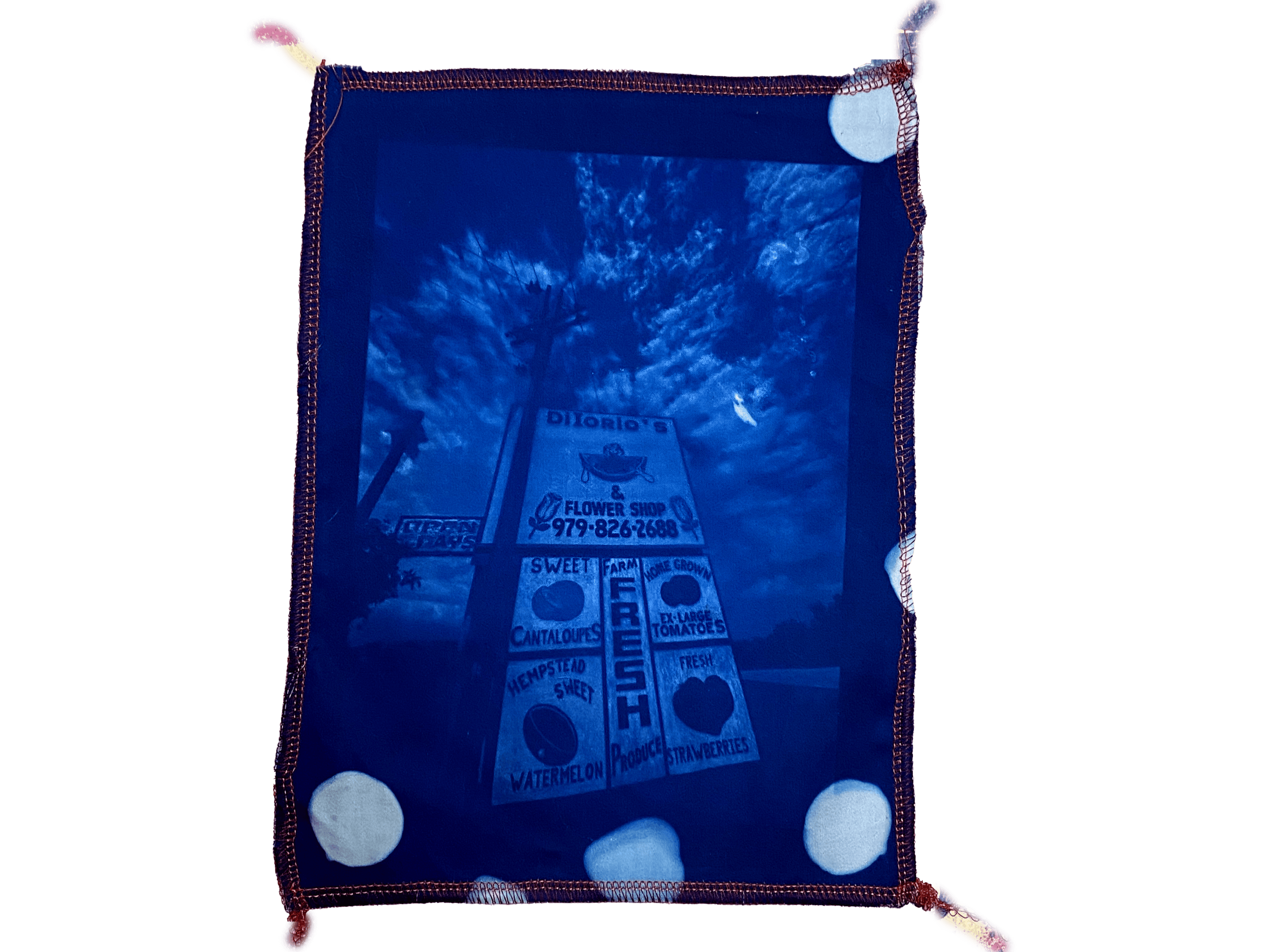

Rian (Raven) Crane, Hempstead, 2024, cyanotype, thread, photograph.

Part One: I’m a mama-papa comin’ for you, Watermelon King and the Black Diamond

“By black here, I don’t mean a particular skin color or identity, a certain vocal affectation, musical aesthetic, or capacity for rhythm (though I do mean all those things, too). Instead, I mean blackness as a radical refusal of the movement of reconciliation, and thus, of whiteness. To be black and to be made black is to take seriously the work of refusal, which is an antagonism, a thorn in the side of the sovereignty of whiteness. . . . To become black is to remain in instability, is to remain in solidarity together in instability. To become black is to be against the movement beyond sociality for the sake of becoming logical and reasonable. To become black is to refuse being made something—to be and become nothing. Not because nothing is an absence or a lack of life, but precisely because nothing is the abundance and multiplicity out of which life is formed.”

—Amaryah Shaye, “Refusing to Reconcile, Part 2”

My father was born in 1945 in Waco, Texas, the eldest of six and the only half-sibling. His mother Johnnie Mae had given birth to him in a first marriage, and he took on her deep beautiful complexion, cheek structure— later passed to me, and undeniable Black Southern country hospitality. My father was an Aries who could make friends anywhere. My grandmother separated from my father’s father and later remarried, something not really looked well upon for the era. With her best interest in mind, my father was raised by his grandparents so that she could easily restart. John and Willie were sharecroppers. Their labor was an exploitative remnant of plantation life, in no way a sharing of crops. It was arduous work on land grabbed by greedy white landowners. Sharecropping, was a form of wage theft meant to keep Black folks from total freedom and in debt under the guise of hired labor, a system formed as a backlash to the Black Reconstruction Era. My great grandparents would take my father to work with them when he was a young boy, so he spent his upbringing accompanying his grandparents to the cotton “farm.” According to my fathers stories, he would often spend time in the main house along with the farm owner’s young white son watching The Lone Ranger, one of his favorite TV shows, which depicted a white settler Texas Ranger who goes rogue fighting crime with a token racial caricature indigenous sidekick and a dog. The Lone Ranger has a moral code not unlike the US Constitution, written with old white cis hetero men of wealth in mind:

“That all men are created equal

and that everyone has within himself

the power to make this a better world. . .

That sooner or later…

somewhere…somehow…

we must settle with the world

and make payment for what we have taken.

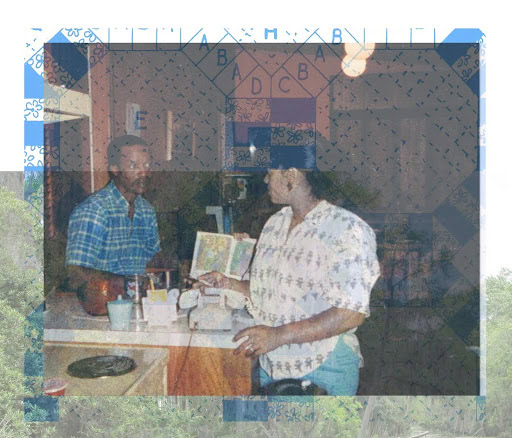

Rian (Raven) Crane, Payment for What We Have Taken, 2024, cyanotype, thread, photograph.

My father witnessed this white man in a black mask purporting to live by a righteous code on the stolen land of a cotton farm. While my father watched The Lone Ranger on black and white television, the first of 2,956 broadcast episodes premiered January 1933 on Detroit’s WXYZ radio. A lot of episodes for a country eager to push media on the masses that affirms it’s retelling of settler histories. Radio was reminiscent of how my father told stories, and eventually of how I eagerly tuned in to listen to his stories. My father sat in a director’s chair next to the corded house phone on our kitchen counter and shared what seemed to be as many tales as there were The Lone Ranger episodes. To tune into his stories, I would choose between taking a seat on the linoleum floor or at the picnic style dining table adored with an 80s style itchy reddish-brown upholstery.

My father’s childhood tales always ranged, how he ran away to the circus as a little boy; a hearse when he was eight as a job ( he was really tall for his age); drank white lighting by accident (my father didn’t drink as a result during his adult life); and swam in Brazos river alongside cottonmouths. These stories filled my imagination with vivid images of Black Texas meridional fables. I imagined white and red candy pinstripe circus tents, massive wide rushing river waters, and black and white TV sets with white men who protect property and manifest destinies from the land’s rightful inhabitants. The Ranger’s manifesto, if thought of as a kind of refrain “we must settle with the world and make payment for what we have taken,” makes me wonder, what unsettled business and payments did my grandparents, father, and Black ancestors have to make as descendants of stolen peoples on stolen land in the so-called US South? Especially in the wake of the climate catastrophe induced by the wealthy imperialists which continues to mostly impact people of the Global South. I learned that the Taino people in the Caribbean noted hurricanes become more frequent once the settlers arrived. The payments or debts seem to arrive along with those first boats of conquest. The indigenous people took note but so did the sky, water, land, and rivers, their relationships and destinies intertwined.

My father’s stories of Black life and frequent visits to Waco growing up helped me make sense of the abundance Black life and nature. Black folks creating a way with horses, dogs, and land, like my cuddin Pumpkin, and visiting my pious also sweetly named family members like Uncle Pie and Aunt Cookie. School and media told me a different story of Global South Black life that painted pictures of red-faced white lynch mobs, poverty, funny accents that no one could understand, boredom, and lack. My father grew up a boy in Texas and then a young boy, and then barely a young adult when he was drafted into the Vietnam War, a farce of war like all US wars that sent young people off to die and be traumatized only to return to landscapes lacking materialities of care. After the “war” he spent time in Michigan in a first failed marriage, in part I imagine due to PTSD after returning home to a country with barren resources and no capacity to hold post war traumas. There he had family and his new wife and after that marriage failed he made his way back down South where he met my mother, who happened to be from Houston, Texas.

My father told me how the war protestors saved his life, and about what I would now understand as a therapeutic and spiritual experience when he attended a music festival where hippies shared popsicles laced with acid and saw someone build a city out of popsicle sticks (a story I’m still not sure the validity of especially in regards to the popsicle stick city). While my father may have had a stint in Michigan he was a Southern country guy at heart and back in Texas my family would visit my grandmother’s house every summer while she was alive. I recall chain link fences with cute silver dogs or lions at the end of each post, a minty green painted exterior on wood, large lawns, driveways, wood paneling in the living room and kitchen, more blue or green. My grandmother’s house always had lots of food, mostly meat, BBQ’d, sometimes chicken, often pork, which my immediate family didn’t eat, and baked beans as sides. I have a fond memory of my grandmother offering me white bread, and me stuffing it all in a 4-year-old mouth since we were only allowed wheat bread at home. I thought this starchy white glucose was as good as gold, and then there was fruit. My father loved cantaloupes, melon, and watermelon—it was one of his favorites. He would often salt it which I tried with him once but prefer it on its own. My father’s appreciation of the fruit’s refreshing properties during the summer meant we often had them at my grandmother’s and around the house.

When leaving Waco, my parents would even take a special trip to the farmers markets between Houston and central Texas, to a town called Hempstead. We would get special varieties like the Black Diamonds, which were given bragging rights as one of the best. The inventor and sole proprietor of that variety was Robert “Bob” Chatham, dubbed the Watermelon King; he wore the title as a badge of honor. Maybe Chatham knew something racists didn’t know about the fruit that traveled from West Africa, and is currently synonymous with an emblem of Palestinian resistance. He was born enslaved in 1859, and became a successful businessman during the height of his career. Chatham had a love for education and opened a school on his property for his children and others of families who worked on the farm. Chatham spent his time between Houston cashing checks at the bank and Hempstead, a route my family traveled often as a child to get the Black Diamond watermelons my parents swore by.

Chatham found a diamond in his earnings of the watermelon variety, a commodity used by white supremacist to mock Black life and culture, he flipped for a shimmering kind of life. I spoke with Mr. Nicketberry, a local Black watermelon seller in my Houston neighborhood. He shared that the variety was special not only for its lovely flavor but thick rind that made it easier to distribute on train cars without bursting. The black diamond, jubilee, or “ jubies” as my mother called them, were among the popular sweet varieties known in Black community and according to Nickelberry much better tasting than the less preferred charleston variety known to white communities. These names are often prized, celebratory, and filled with lore like my fathers childhood.

Not to romanticize Black capitalism or entrepreneurial pursuits, but there’s something dialectically interesting about the variety title Black Diamond, the man who stewarded and a king of a life he made out of it. The Watermelon King’s reign was not forever.

In the post-emancipation south Black farmers were able to self sustain growing crops like watermelon, which was initially unattractive to white farmers. The stewarding of land offered a loophole of retreat from centuries of spiritual and bodily dispossession. What did survival entail, specifically Black survival, in a climate meant to be politically as unbearable as summer’s humid heat? If as Imani Jacqueline Brown writes, “Black Ecologies is a multigenerational, multidimensional dialogue and a reminder that Black resistance is always already tending to other ecologies of being(s),” then wasn’t the watermelon, this fruit in name and being tending to, a reminder of Black Resistance?

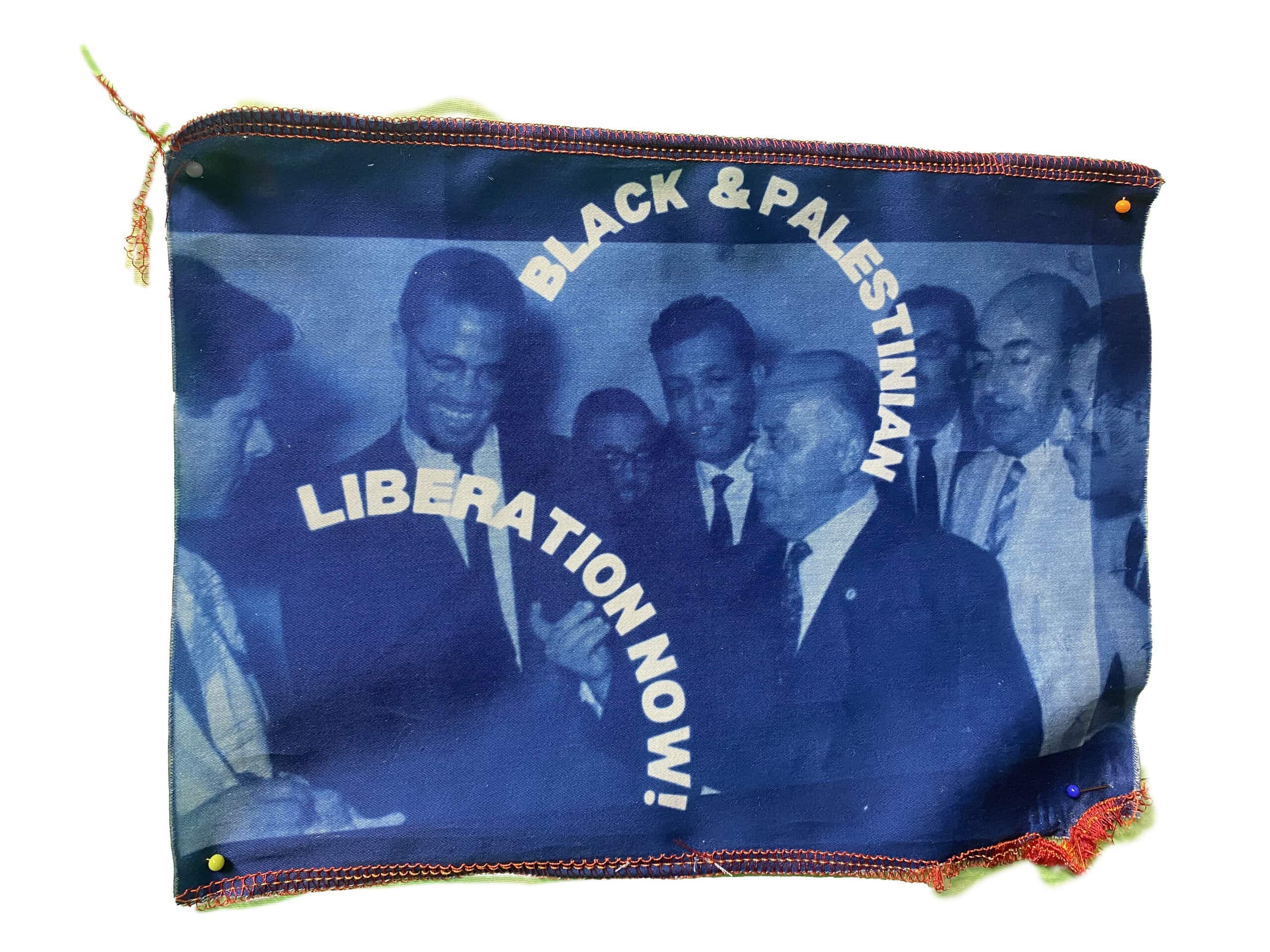

Rian (Raven) Crane, Where will You be? (In Solidarity), 2024, cyanotype on cotton fabric, thread, historical and photos of Lulling, TX.

A marronage age daydream, a reference to David Bowie’s moonage daydream, a song I listened to frequently as a rock and roll obsessed teen with a mullet to tow who spent time listening to both oldies rock and who was in the never-ending pursuit of queer people, Black people, and their musical contributions as originators and innovators of rock and roll music. Bowie belts out in moonage age daydream.

“I’m an alligator

I’m a mama-papa comin’ for you

I’m the space invader

I’ll be a rock ‘n’ rollin’ bitch for you . . .”

(Bowie, 1971)1

Pulling freedom analogs from rock and roll’s ineffable spirit of rebellion beyond aestheticism of youth, avant-garde hairstyling and clothing, drug de-stigmatization, and spirit of looseness there is space for imaginative and freedom belting in song, enmeshed as one. Rock and roll is queer, while not all musicians are queer the aesthetics created by folk like Little Richard, who donned a Bouffant, rich dark eyeliner, the gender non normative way of emphasizing being pretty is queer Black culture. Rock music meant loud, string heavy, shaking both in bodies and reverberation. It meant a turning upside down of christian normative ideals of purity, whiteness, and piousness, all arguably traits of anti-Blackness even pre-global colonization during their European conception.

“Trans* is a disruptive orientation but it is not for me specific to transgender bodies, it is rather a method or mode of engaging time, history, people, things, places with an openness and an acceptance of the excesses that are constantly being created and unaccounted for. So Trans* does not denote bodies and the work that bodies do, it is rather an acknowledgement that bodies do, be doing and they might be transgender, gender- non-conforming bodies that do the work of disrupting heteropatriarchy, but it is not a guarantee that certain bodies always do a particular work.”

– Where Black Feminist Thought and Trans* Feminism Meet: A Conversation with Kai M. Green & Marquis Bey3

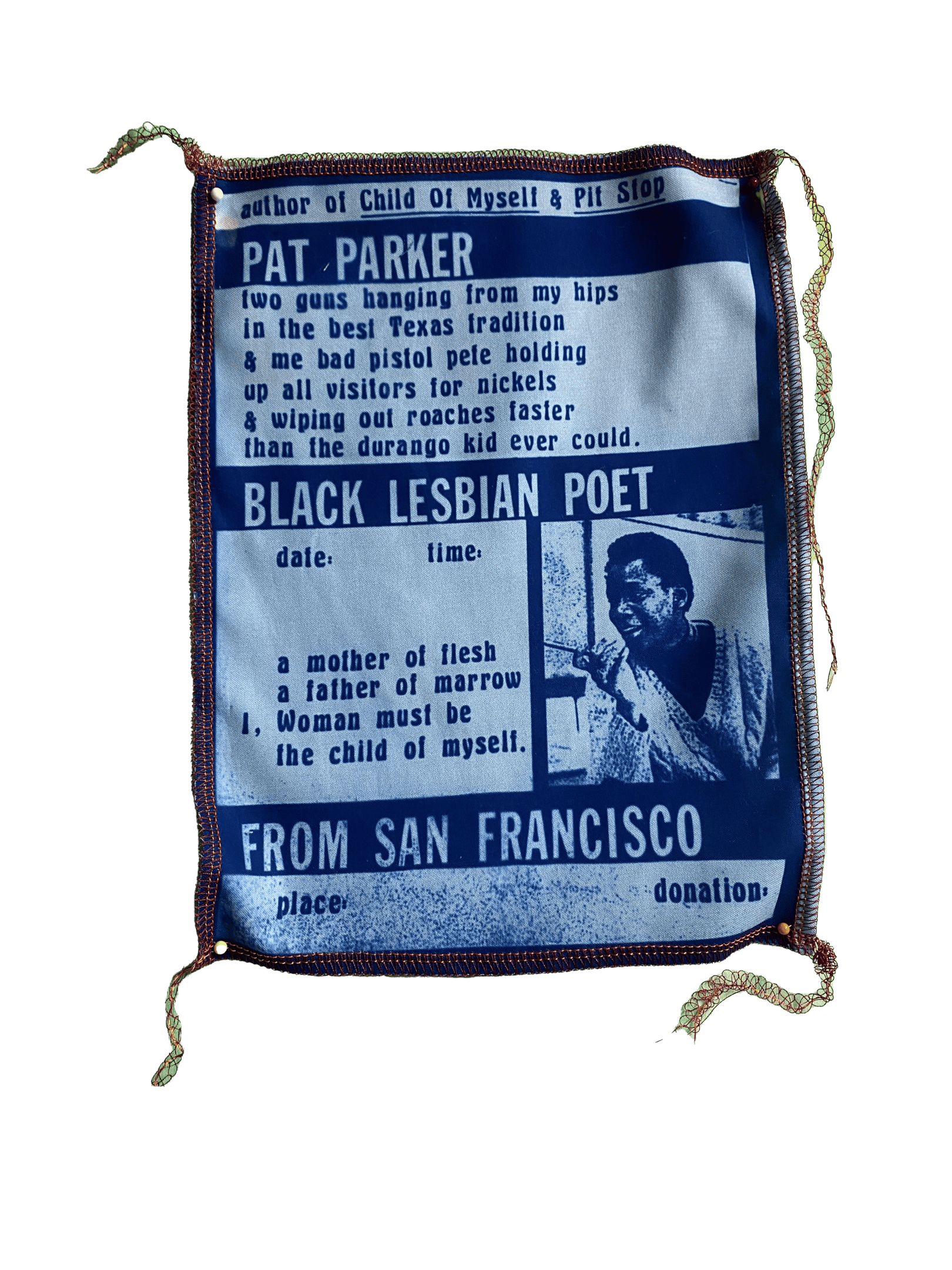

Rian (Raven) Crane, Where will You be? (When They Come), 2024, cyanotype on cotton fabric, thread, historical and photos of Lulling, TX.

Houston, Texas born poet Pat Parker writes to Audre Lorde in Sister Love: The Letters of Audre Lorde and Pat Parker 1974-1989 about her return to Texas for a poetry reading. She details her coming out to her mother, her approval much to Parker’s disappointment. Parker’s mothers says “Well as long as you are happy it’s alright with me,”2 a stark contrast to most mainstream media displays of queer people coming out. She does a reading in that same trip and speaks of a Black woman reporter who fearfully interviews her, only getting “closer with the mic once her arms were tired.” The reporter is frightened of Pat’s queer and masculine gender non conforming queer appearance. In one of her poems, Parker addresses her childhood obsession with wearing cowboy boots with every outfit. Parker’s butchness and tales of the South connect to the spacious lands’ ability to hold queerness and is testament to the south always having queer and trans people. In fact according to UCLA’s Williams institute the south has the most trans people. A data point that should make it clear that the current wave of policies is an egregious pointed attempt at erasure and suppression. Much like the turning of the watermelon into racist caricature once Black folks in the south became successful stewards of the crop, one of the oldest tricks in the books by those in power who feel threatened is to try to warp narratives. The gender expansive Black South is a place not only marked with the policies of the imperial core but also by the people and land.

If the Black Diamonds’ legacy and the Watermelon King4 represented a larger than life fruit, then what does one find in the sugar baby, a tinier variety of melon? The skin and flesh according to The Gardener’s Basics is dark green with faint striping and mottling vibrant red and pink, with a thick rind surely a relative of the Black Diamond, its popularity stemming from the small size being ideal for home gardens and to fit in your icebox. Sugar Babies are the queers, trans, the sex workers, the poor, those who work the land and cities and keep the world afloat with culture, mutual aid, and essential services running. Sugar Babies are not the elite, the people at the intersection of power of any identity but those who are at the frontlines of resistance. Their power is meant to feel small but they are thick-rinded, plentiful and essentially able to pop up it seems with smaller resources. Sugar Babies are accessible, access is key to a people’s movement.

The watermelon for me feels akin to what Kai M. Green refers to when he says “Black feminism is the texture of the excess, the quality of the critical overflow that escapes capture, one that must continually be remapped, undone, redeployed, and worked, worked, worked.” (Green & Bey, 2017) The continuous work of soil tilted and turned gives way to life as Black Diamonds and Sugar Babies are a source of refreshment, nourishment, liveliness. The watermelon can be remapped, undone, and redeployed as it was in the 1980’s and currently by Palestinian activists as a symbol of revolution. I am not writing or making art to romanticize the watermelon, for Black or Palestian which are seen as intertwined, since no struggle or difficult thing should be, it’s rather what’s on the other side of that struggle for oppressed people that is the end goal. I’m instead trying to explore how propaganda, intentional racialized disinformation attempts to obscure entire histories make folks forget and sometimes lead to complacency. It’s so critical to know history, make connections, and to trouble narratives, to remember that the south is a place marked with just as much resistance to oppression as strife.

Rian (Raven) Crane, Where will You be?, details of triptych, 2024, cyanotype on cotton fabric, thread, historical and photos of Lulling, TX.

References

[1] Bowie, D. (1971). Moonage Daydream [The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars]. RCA.

[2] Enszer, J. R. (Ed.). (2018). Sister Love: The Letters of Audre Lorde and Pat Parker 1974-1989. A Midsummer Night’s Press.

[3] Green, K. M., & Bey, M. (2017, October–December). Where Black Feminist Thought and Trans* Feminism Meet: A Conversation. Soul: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Culture, and Society, 19(4), 438–454. http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/usou20. 10.1080/10999949.2018.1434365

[4] Shaye, A. (2014, February 16). Refusing to Reconcile, Part 2 | WIT. Women in Theology. Retrieved August 15, 2024, from https://womenintheology.org/2014/02/16/refusing-to-reconcile-part-2/Smith Prather, P. (1989). The Watermelon King Remembered.