I met Erin Jane Nelson through a good friend of mine who recently moved to Brooklyn. She introduced Erin as a young but mature upcoming artist who relocated to Atlanta from Oakland about a year ago. In addition to Erin’s art practice, she runs the gallery Species inside of her studio at Atlanta Contemporary with her partner Jason Benson, another new transplant to the Atlanta art community. Both Erin and Jason are showing nationally and internationally, and both have also been selected to participate in the upcoming Atlanta Biennial at Atlanta Contemporary, placing them among the few local artists included.

Jiha Moon: I have known you for a short time, but you are still new to many in the Atlanta art community. How did you and Jason decide to move to Atlanta, and what was your life like before in New York and Oakland?

Erin Jane Nelson: Most of our friends and peers had moved away from Oakland to New York or L.A., where it’s become slightly more affordable to live than the Bay Area, but we were fed up with the rat race of trying to maintain both home and studio rent in such high cost cities—it felt that either of those choices would be more of the same. I grew up here and have always thought that, for all of its industry and music and food, Atlanta seemed glaringly missing from the larger American emerging art world. I was hearing about spaces and artists in Nashville, Memphis, New Orleans, and Birmingham, but was never hearing about Atlanta. So a mix of curiosity, family, and sustainability made it an easy decision.

JM: You are one of hardest working young artists I know. You are not only showing all over the place but also running a gallery. You also often travel to do workshops and studio visits with artists, and sometimes you write, on top of keeping your daytime job at the High Museum. How do you balance all these activities? How do these different roles affect you as an artist and your work?

EJN: I’m flattered that you think I have these things balanced when I definitely do not! Most of the time I am either time-poor or money-poor, and even more often I am both. Although my top priority is to be an artist, I also love exhibition-making, writing, and research. I’d rather spend my time and money working in service of other artists than … going to brunch, for instance. Being a morning person helps.

But I don’t think it’s advantageous to have so many different roles. Even if they all help support my art practice is tangential ways, I always end up wishing for more time in the studio alone with my thoughts.

JM: I find this tendency in the art world that more and more artists are running galleries these days. I think artist-run galleries tend to allow artists to test their creative limits because they are not primarily concerned with the business side of things. Do you see Species that way?

EJN: Species is mostly a way for Jason and I to remain connected to our friends and artists we admire who live outside of Atlanta by inviting them down to make exhibitions. We would love to make money or even break even with the gallery, but from what we’ve seen elsewhere, letting artists make the work they want to make and subsequently having strong exhibitions and a distinct program will—hopefully—lead to some form of success either for the gallery or the artists involved or both. Although we don’t organize exhibitions with the expectation of making money, we really try to avoid being slapdash and overly casual. We don’t want artists to feel like they’re missing anything by showing with an artist-run space.

JM: That’s a good point. Species travels as well. You and Jason have curated shows elsewhere, including the recent group show “Peachtree Industrial” at Bodega in New York [in which Moon’s work was included]. The Fuel and Lumber Company in Birmingham is run by another artist couple, Amy Pleasant and Pete Schulte. Both spaces are not geographically fixed and can move to other places for exhibitions. I love this idea of a fluid gallery moving around. Do you see your future projects evolving more in this way?

EJN: Maybe… We enjoyed organizing the group exhibition in New York because it was a way for us to bring some of the artwork we had seen and loved in the South to a New York context. However, we don’t imagine ourselves as professional curators, so while it’s nice to do off-sites every once in a while, it’s not a core part of our goals. We have been lucky to have several other invitations to bring the gallery to San Francisco and even Berlin, but are primarily focused on the next four shows at Species that will happen by the end of 2016. We are still figuring out how much bandwidth we will have for 2017 and beyond and whether organizing both locally and outside of the South is feasible.

JM: Let’s talk about your artwork. I very much enjoy your sensibility of using images and materials that are both odd and familiar, such as pictures of your surroundings and yourself. What is your process of material and image hunting like? Do you find your materials based on a specific narrative or message?

EJN: I come from a traditional photography background, so the majority of the images in my work are photographs that I have made. The other sources, like fabric, screen-captures, and patches, are often collected over time with a broader project or thought in mind. Usually I have a semi-formed narrative or intent going into a piece or a group of works, which often leads to very deliberate material decisions. It’s never purely formal and intuitive.

JM: Can you tell us about your quilt series? How did you get started?

EJN: In 2014, I had been making craft-based work, both in the traditional sense with pottery, glass, and woodturning, and in a more tongue-in-cheek contemporary sense by riffing on suburban DIY projects à la Pinterest or Etsy. At the same time, I was also making these really digitally affected photo collages and videos. The info-quilt or photo-quilt (a medium that has its own mini-history in contemporary art) seemed like the perfect way to join these previously separate lines in my practice. After I made the first piece (originally as a one-off), I became infatuated with the form and process and have made tens of them since.

JM: The images you use range between autobiographical images like your selfies to somewhat ridiculous (this is one of my favorite English words!) images like your little dog wearing an outfit you made. More recently, I see you are layering images of octopuses and yourself wearing a mask [onto the quilts]. Do you always know where you are going in terms of image development and material mashup?

EJN: I’m interested in all the “linguistic” possibilities of photographs and I think the range of images I use in my work reflect this. Humor or ridiculousness is one of my favorite tones because it disarms some of the pomp and classism of a gallery space and the art world at large. It also seems like a productive way to deal with anger, hopelessness, and anxiety which—with the state of affairs politically, economically, and ecologically—are feelings I experience a lot.

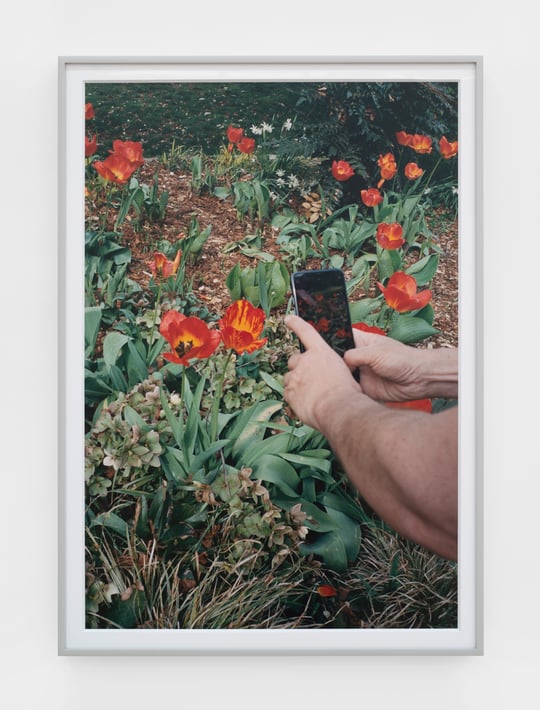

JM: That’s a great way to deal with the world and make art about it. Throughout all these mashups in your work, I see images of social networking and cell phones. How are you thinking about these things in your work? With your image-making, what are your thoughts about current communication trends around the world?

EJN: All of my imagery deals with the ever-evolving relationship we have with photographs and screen culture. Like you mention, many people now communicate with images more than with written or spoken language, and I love this about the moment we live in and want to unpack this in my work. That being said, we have a much better understanding of the sociopolitical aspects of spoken and written languages compared to what we culturally understand about images. I’m eager to see some of the politics of images better understood by everyone who uses photographs to communicate—there is still a lot of work to be done.

JM: Even though it seems that spoken or written languages have power to communicate, I see misunderstanding happening all the time in many situations. It’s the same with visual languages, though, especially in social media. People are quick to judge what they see and label things. The way people deal with these images totally influences the way they see art now.

EJN: Exactly—having good photo documentation, for example, has become so integral to an art career or a gallery program, for better and worse. If it weren’t for the Internet providing portals into larger art cities like New York or Los Angeles, I don’t think it’d be possible for me to live and work outside of those places. On the negative side, I find a lot of emerging art begins to look the same because everyone with a BFA and a smart phone is looking at the same art blogs and gallery websites. Over history, though, these double-edged swords of technology and advances in communication always seem to resolve themselves and become generally accepted practices and communication methods.

Jiha Moon is an artist living and working in Atlanta. Moon’s solo exhibition “Double Welcome: Most Everyone’s Mad Here,” organized by the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art and the Taubman Museum of Art, is on a national tour through 2018. She is represented by Ryan Lee Gallery in New York and Curator’s Office in Washington, D.C. Moon’s work is included in numerous public collections and museums.