Opening the same night as pair of solo exhibitions by artists Sascha Braunig and Paul Anthony Smith, Steffen Sornpao’s installation Can I get 1G in the chat? was the third mini-exhibition featured in the Sliver Space at Atlanta Contemporary. Given its esoteric title and central object, a carved wooden monkey gesturing with a raised middle finger, the installation left some viewers snickering and others wondering aloud about its meaning.

Sornpao, now a 2017-18 Walthall Fellow, has since shown new sculptural work—a departure from photography, which he studied at Georgia State University (BFA 2015)—at the artist-run space Mild Climate in Nashville and Atlanta’s Hi-Lo Press. Since 2016 he has been co-director of Good Enough, a gallery in the basement of the house he shares with artist Jordan Spurlin, which has shown work by artists including Craig Drennen, Cosmo Whyte, Mika Agari, and, until September 15, Chicago-based artist Kira Scerbin. I visited Good Enough last month to see Cody Tumblin’s exhibition It Blooms Tomorrow, and afterwards Sornpao and I drove a short distance from his house in Capitol View to the nearby warehouse where his studio is located. The wooden monkey from Can I get 1G in the chat? sat near the studio’s entrance.

Logan Lockner: I remember seeing this [Can I get 1G in the chat?] at Atlanta Contemporary earlier this year.

Steffen Sornpao: Yeah. That was really cool because I had just happened to walk in there to check out the Lonnie Holley show with a friend and ran into Daniel [Fuller, curator]. He showed me the Sliver Space and told me he wanted Atlanta artists to propose projects for it that were not like their usual work. I was pretty much doing a 180 with what I was working on, so we thought it could be a great fit.

So this happened at a time when your work was changing a lot. What kind of work were you making beforehand, and what inspired the 180?

I had been an illustrator and a painter growing up, and when I got to Georgia State I decided to throw myself into something that I had no knowledge of or preconceived notions about, so I took a photography class and really liked Jill Frank, and she pretty much won me over. She was really smart and discussed so much more than just photography. The photo program is very conceptual—you think about your process the whole time but are also constantly doing research, so it was very thoughtful and engaged on a conceptual level. I definitely think studying under Jill in that program helped me grow a lot, because before I was just some shithead painter kid.

(Laughs) I was looking back at Dispose, the photo-based installation you curated at the Low Museum in 2014. You were working with photography in a conceptual way.

Definitely, but doing installations with photos is not a part of what I do anymore. I ended the photography program leaning more into sculptural stuff. I was encasing photographs in silicone to play with the physicality of the paper, and then made wooden structures, like little playgrounds, for them to interact with. For one of the final assignments with Jill, we were supposed to do a photography project with three-dimensional elements, and that actually jump-started my working with sculpture, which is basically the focus of what I do now. My last photo-based project was for “Print or Projection” at Swan Coach House Gallery, and then I reverted back to painting.

I remember seeing one of your paintings in the first Good Enough show.

Yeah. At that time, I got really into graphic-based imagery and started collecting all these graphics I would find on packaging or see while shopping. I became really obsessed with decals, and also just kind of Southern—I don’t know if trash would be the right word—but just like kitschier Southern things. I was going into gas stations and finding weird knickknacks and applying that imagery to my work.

Your painting [Very in Pain] in the Good Enough show was propped up on sweet and sour pickles, for example.

(Laughs) Yeah, but I’ve never actually eaten one; I was always scared. But I did love the little pickle people on the front. I just thought they were funny little feet, kind of like little clownish shoes.

Have you lost the interest in that graphic sticker imagery?

I still get excited when I see it. I don’t want to touch that with my work, at least for a while. When Anthea [Behm] was here showing at Good Enough, I talked to her about it because I felt like it was really gimmicky. It was silly, and I enjoyed the silly aspects of it, but I was kind of starting to take myself less seriously and started assuming other people were taking me less seriously too. I was just haphazardly making things with these graphics that were aesthetically pleasing, but it felt empty to me.

That’s when I moved into making this new stuff, ’cause I felt like there was more emotion to it, more that I could take away. A lot of the stuff I’m working on now draws on environmental themes and ideas from groups like Greenpeace. I’ve been researching preppers and survivalists and the notion of living off the grid, and examining this trend of returning to nature. I’m sourcing a lot of my materials from thrift stores and trying to find ways I can leave less of a footprint while making things.

That does feel like a departure, but I also see further developments on ideas you were already exploring. There’s a continued interest in subcultures in a way. The wooden figure in Can I get 1G in the chat? reminds me of something you’d see at a truck stop somewhere in the South.

For sure. That one pretty much came from an interest I had in chainsaw carving.

You carved that with a chainsaw? That’s crazy!

Yeah. The log actually came from a friend of mine whose car was totaled by a tree that fell in her backyard during a storm. I wanted to use the wood from the fallen tree as material, but I also like its backstory — its final will against humanity was to crush the technology that’s hurting nature in some sort of way.

The monkey figure in Can I get 1G in the chat? flipping off the viewer is like a metaphor for what the tree did to her by destroying her car. Where did that image come from?

I scour Amazon every now and again to see what the heck you can buy on the Internet, and I found these monkey figurines that are about six inches around. It’s such a weird thing to buy, but I also thought the image was great. I’m trying to place that figure back in the context of environmental activism, like the monkey is a sort of messenger of nature saying, “Fuck y’all, thanks for doing this to us.”

What about these little gourds?

I was researching bushcraft tactics on YouTube and came across this video about how people can use gourds to capture monkeys, and then use the monkey to locate water. You carve a little hole that’s just big enough for a monkey to slide its hand into in a gourd or an anthill and put food in there. Once the monkey puts its hand in and grabs the food, its fist becomes too big for it to pull out, and then you just grab the monkey. It illustrates this notion of trying to take more than you should, something you see as beneficial but which actually jeopardizes your situation. I put rice pearl beads in the gourds because I wanted something in there that appealed to humans as a metaphor for pearls or precious stones or even currency.

The paracord around the gourds actually comes from survivalists and preppers. They’re obsessed with paracord, which is like an army-grade rope originally used in the suspension lines of parachutes. There are all these survivalist ways to use it, like building shelters or making splints—it’s a really useful thing to have. But what I find interesting is that the survivalist community has found really ornate ways to wrap everything they have with paracord, to the point where it seems excessive for a survival tool. Why should it be so intricate, with all these knots and weird patterns, colors and variations?

Where does the title Can I get 1G in the chat? come from?

That came from comments on a YouTube video. After finding that bushcraft video about the gourds, I went down a rabbit hole of watching gamer videos, and in the comments someone kept writing “Can I get 1G?” and I got really curious about what that meant. It’s based on the story of a professional gamer called Summit1G who was playing a match of Counterstrike, which is an online army first-person shooter game. All the other players were dead, and in order for his team to win, all Summit1G had to do was defuse a bomb by pressing a button. But as he was walking up to it, he accidentally threw a Molotov cocktail and killed himself, and the other team won. It echoes the story of the monkey trap, this notion of being so close to victory and accidentally causing your own destruction.

What you were saying earlier about my interest in subcultures is true, I guess. I get really excited about finding weird little pockets of meaning that are specific to these communities, and then bringing them together to create a bigger context. But I also like the conceptual distance between a phrase like “Can I get 1G in the chat?” and these objects, because even though the connection is there, it isn’t obvious.

How do you think about that gesture of appropriation? I can imagine seeing these paracord-wrapped gourds hanging off the side of a barn and not really recognizing them as art objects, but obviously you’re intending them as sculptural elements.

I don’t mind that they can be perceived as non-art objects. My original idea for the Sliver Space show was that the pieces would be art objects but that also, if Armageddon came, you could run into that space and grab these things for their functional use as survival tools.

These caltrops were part of that show too. They’re actually road spikes that the Earth Liberation Front and other eco-activists use. I read about them in Ecodefense, which is this book that pretty much step-by-step shows you how to make traps and different sorts of objects to deter activity by logging and shipping companies, how to infiltrate and mess with them. If a tire rolls over these caltrops, they pop the tire and the vehicle can’t move. But I wanted to stick feverfew in the caltrops because it’s used as a traditional herbal remedy, and I really liked this image of the feverfew standing up as if it were living.

I noticed that the titles of your work have also been becoming more poetic, especially with the pieces you’ve shown recently at Mild Climate in Nashville and Hi-Lo Press in Atlanta.

I’ve been trying to work on writing more and became really interested in writing poetry. It’s a very recent development. Like I said, I was afraid of my work becoming gimmicky and superficial, and I felt like I could maybe avoid that by forcibly applying some romanticism and poetry to the new work—but I don’t know, maybe that’s a façade.

What really kicked me into writing poetry was finding Sydney Shen’s work. I really enjoyed the emotional experience of seeing her work and reading her writing. She and the graphic designer Laurel Schwulst collaborated on a writing project called Perfume Area, where each of the texts is a review of a perfume or a scent, and I liked how eccentric and situational their use of language was.

And like Can I get 1G in the chat?, poetry creates ambiguity and distance between the object and its title. These new poetically titled objects you’re making also feel totemic, almost like religious objects of some sort.

Yeah, I’ve started to understand them as little shrines. I’m interested in people’s understanding of the sun and its relationship to the Earth, as well as older civilizations’ ways of using sunlight with Stonehenge and structures like that. The piece at Hi-Lo has a sun-shaped object welded on the bottom, and on top there’s a brain made out of wax and sawdust, which survivalists use in smaller quantities to make fire starters. I wanted to connect this wax-and-sawdust brain to the story of Prometheus and how humans gained knowledge of fire. The piece is like an offering at a shrine, where the brain stands in for humans’ knowledge of fire. At the opening at Hi-Lo, the brain was actually on fire—outside, of course—and being this size it actually burned for a few hours. The poem that serves as the sculpture’s title is about burning the brain as an offering to the sun, relinquishing knowledge of fire and bringing humanity back to around two million years ago, just before that knowledge was discovered.

It sort of inverts the traditional way of understanding offerings, because you usually make a sacrifice to gain something, not to give it back. It’s almost like an exorcism.

Yeah, exactly, getting rid of even the most basic human technology.

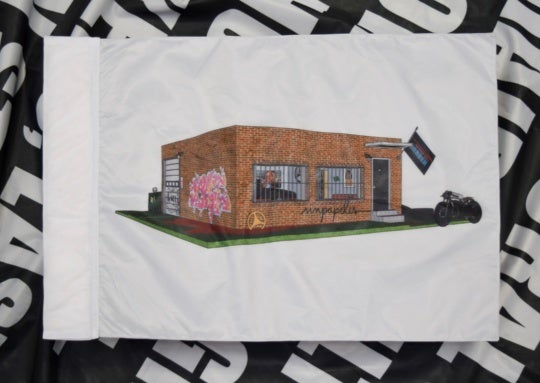

Tell me about Good Enough and how you decided to have a basement gallery.

I had always wanted to have some sort of space. I was looking at people like Austin Eddy, who has EDDYSROOM, and this space in Brooklyn called Ryobi Room, which is in the basement of a bodega. When we were looking at this house, the realtor mentioned that it had a weird basement we could use for storage. She opened the trapdoor and we walked down, and I was like, “We need this house now!” I thought the weirdness of the basement added so much; it’s not just a matter of arranging things on white walls.

The first two shows at Good Enough were group shows, but since then you’ve focused on solo shows. What led to that change?

After the second group show, which was my first experience reaching out to out-of-town artists, we decided on doing solo shows. I want the space to draw artists from other cities to Atlanta and give people here a chance to form personal connections with them, creating a broader community. It hasn’t really happened yet, but I also hope that, if the possibilities arise, future curatorial projects outside of Atlanta will be a way for Good Enough to show Atlanta artists elsewhere and add to that flux.

By bringing out-of-town artists to Atlanta, it seems like Good Enough is in conversation with other artist-run spaces in the city, especially Species and Wreath, which have similar programs.

I was really excited when I found out about Erin [Jane Nelson] and Jason [Benson] running Species. I loved what they were doing and made a point to go meet them and check out their space, and we’ve become friends. Every now and again I reach out them with questions like, “How do I do this with the space?” or “How do I reach out to people? What’s your experience?” It’s been nice having them down here because I’ve been able to learn from them, and having Species here has set a high standard for artist-run spaces for Atlanta. I’ve always wanted Good Enough to have a certain level of seriousness when it comes to the consistency of the program and the quality of documentation. Artist-run spaces in Atlanta tend to be really bad at documentation, but being diligent about documenting our shows and using social media and Instagram to share that documentation has helped to put Good Enough on the map.

Logan Lockner is an Atlanta-based writer and a contributing editor of BURNAWAY.