Originally from Decatur, Illinois, Craig Dongoski has lived in Atlanta since 1999 and began teaching art at Georgia State University in 2001. We met with the artist earlier this year to discuss his upcoming show at Whitespace (May 17- June 21), titled “The Primates Notebook.” The title refers to the source material—marks made by a language-trained chimpanzee named Panzee—as well as essay by Erik Satie titled “The Mammal’s Notebook.” The exhibition is the culmination of his interaction of over two years with chimpanzees and research scientists at GSU’s Language Research Center, which has deeply affected his work.

On February 9, a week after our visit, Panzee died unexpectedly. Born and raised in captivity, she was 28 years old and diabetic. In a recent email, Dongoski said: “My closest contact with Panzee (both physical and emotional) is with the writings/drawings that Panzee produced. Incidentally, the last recorded activity of Panzee was of her drawing on February 6, 2014. My next body of work will center around this set of marks and the video document. The exhibition will be dedicated to Panzee’s and Michael Owren’s memory. Michael Owren was the scientist whose research in sound with the chimps provoked my initial interest in the lab. Sadly, he passed this year as well.”

Stephanie Cash: Tell me about your artistic collaborator of the past few years.

Craig Dongoski: She’s a chimpanzee named Panzee at the Language Research Center. A lot of people are familiar with Koko, the ape who used sign language, and there are various researchers doing interspecies communication. This particular lab works with a set of lexigrams comprised of arbitrary symbols. There are three panels that include 128 lexigrams per panel. A lot of them are food-based—like a banana, an apple, a sweet potato—but some of them are more abstract—like different feelings and actions. There are four chimps at the center, but Panzee was the one that I engaged with the most because she has developed a propensity for writing.

SC: How does that relate to your practice?

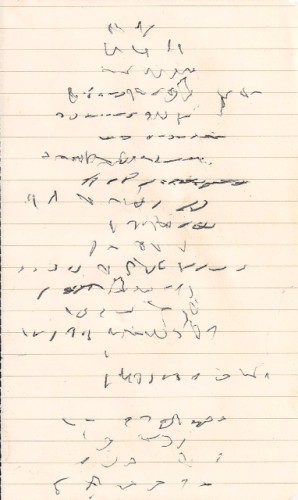

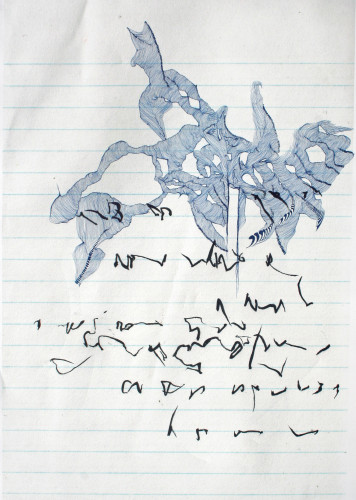

CD: My work has always been concerned with the question of where drawing ends and writing begins. I’m very interested in this gray area, particularly the artifact of the sound of mark-making. I happened upon the lab on its webpage. They were using vocoders and scrambled signals to determine if the chimps could understand the word rather than respond to familiar voices and behaviors from the caretakers and scientists working closest to them. These were tools and curiosities I was essentially involved in with human inscription. At the time, I didn’t know that Panzee could write. I went to the lab to record the chimps vocalizing, and then I learned about the things she would do on notebook paper. It really captivated me. In addition to the notepaper she’s familiar with, I introduced her to writing on graph paper and musical score paper.

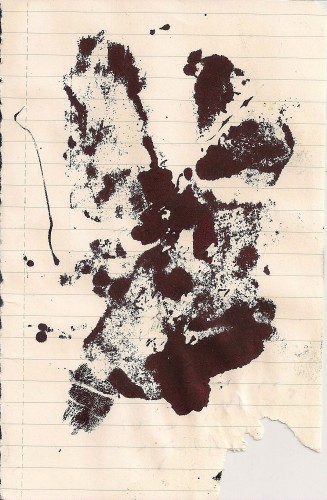

I’ve primarily been thinking about language—how we learn to speak and how we learn to write is through repetition and copying. So, the show is a display of the collaboration/interaction between her and I. I receive what she writes then copy it as a way to internalize her mark making. The majority of the show is going to be based around this particular note page. It will be framed alongside a handprint made by her after biting the pen’s top off and being covered in oozing ink and having the thought to stamp her hand on paper.

I see these pieces representing two forces of modernism: Surrealism and German Expressionism, as embodied by Michaux and Arnulf Rainer. The two pieces [see below] done by Panzee are representative of these two strands. The glyph-writing resides in Michaux’s impulses while the handprint is a reference to Rainer. I’d like to think I’m within that conversation.

I’ll also be doing a performance at Whitespace with a text-sound poet.

SC: What will that be like?

CD: The primary scientist I work with, Charles Menzel has worked with Panzee since she was 11 years old, is recording a lecture, probably a lecture about how animal behavior studies helped pave the way to modern psychology, which we’ll record and I’ll manipulate.

There is a subset of works called Pronunciation Poems. These are modeled from an idea of the 16th-century Dutch mystic Mercurius von Helmont, who had a theory that all Hebrew characters resided naturally and inherently in the throat. He made pronunciation diagrams to illustrate this. I’m using this model to guide the performance as well as using the diagrams as a matrix for some of the works featured in the exhibition.

SC: So, Charles is going to put sound to the lexigrams?

CD: He’ll actually pronounce them. I’m working with James Sanders, who’s with the Atlanta Poets Group. He has done a nice job with creating an index-lexicon and analysis of each one of Panzee’s characters and has assigned a pronunciation to them.

SC: Will you have other samples of her writing?

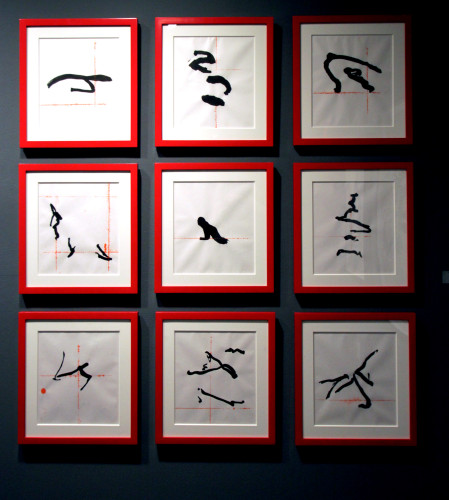

CD: I’m going to have at least two walls fairly densely presented. I’m modeling it loosely after ancient Chinese schoolrooms that were used for teaching language.

Desmond Morris is a very famous primatologist. He’s been writing about nonhuman primates since the ’50 and ’60s. He’s an artist who’s about 85. He’s done many television shows and books; one of his most famous was The Naked Ape. He also wrote The Biology of Art and contributed to a book called Monkey Painting. He and I have been corresponding recently, and he’s going to contribute a quote that I may include in the show.

SC: Are these being translated into music?

CD: I think of this work as being about graphic scores as much I think of them as paintings. This is that gray area between drawing and writing I was talking about. This is the reason I’m working with the sound poet and musicians..

SC: [watching a video of Panzee writing] It’s amazing how precise she is.

CD: Desmond has two or three chimps that he’s been working with closely, and we’ve been swapping chimp writings and drawings back and forth. He thinks that there is some sort of gender difference. He sent me some writings and drawings from his chimp Congo, and they’re straight, scratchy marks, but his female chimps have more complex systems.

SC: How do you incorporate Panzee’s writing into your works?

CD: I’ve worked with repetitive mark making for a while. So, instead of random shapes, I’m starting with her characters. I see them as resounding. I repeat the contours of her marks over and over again. That’s why I see them as structures. I have it in my mind that these will become sculptural at some point and making these characters dimensional is a pathway to that.

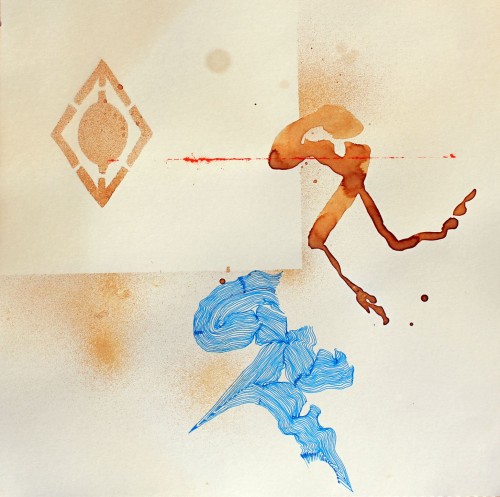

This overdrawing is related to Arnulf Rainer and Henri Michaux, and the sacred and profane act of drawing over something but being mindful about it at the same time. I’m consumed by that paradox.

SC: But you’ve been doing repetitive mark making for a while, before Panzee.

CD: It has a precedent. I was having success with them and they were really good for my mental state and I liked that they were just about nothing. But I was feeling like I wanted something else with them. Meeting Panzee and this experience started to pull me in a really interesting direction. One of my favorite movies is Altered States. I love what was happening in the ’60s with science and art. There was no kind of restraint; people would just experiment. Working at the lab makes me feel like I’m within the continuation of that spirit … ya know, the kind of spirit that allows someone to go to the moon.

SC: Where do you want to go next?

CD: In some of these smaller pieces, I’m working with words that I write on the back of a sheet a paper. It’s random. Sometimes I will take 100 sheets of paper and just make a list. It’s kind of like a loose-leaf sketchbook. It’s a way to think of a sketchbook differently, and it introduces chance. I have over 100 of them.

SC: What are they made with?

CD: They’re done with lemon juice and put in the oven. I’ve always been interested in Joseph Beuys’s rust paintings. They resonate with me in terms of cultural and historical significance while possessing an alchemical quality. The lemon juice results in a similar visual outcome. This technique is also used to write “secret messages,” like invisible ink. I think that the materiality of food is something that Panzee is directly connected with and is profoundly significant regarding her relationship with humans. I’ve also made ink out of walnuts and blueberries and used it to paint her marks.

SC: I see you’ve made these marks in different materials.

CD: Some are collagraph prints that I’ve drawn on. Some are prints on prints. Collagraph is a process that was developed in the early 20th century out of the WPA [Works Progress Administration]. It’s literally “collage-drawing” and is a poor man’s printmaking. I’m trained as a printmaker but hadn’t done prints in over a decade. I suddenly got the bug and was working like a maniac for four weeks.

SC: Why do you use wood panels instead of canvas?

CD: People ask, How do these drawings come about? I say, think of a Bonsai tree, or of tree rings. The drawings are an exact mimicking of these growths, setting up an indeterminant outcome. I have a history with wood too. My father is a carpenter and woodworker, and I’ve been around wood my whole life. I also think about how Brice Marden used to talk about painting: if you paint a tree, use a scion from that tree. You keep it all connected, the physical material of it producing the pictorial result.

William Morris said there can be no art without resistance in the materials. There is something about inscribing on wood, where I can’t control it, and it does create these types of mutations. It may be a reason that I like working with wood. You can see the work on paper is a lot more controlled and steady, and that has a particular kind of look and outcome, whereas the marks made on wood have more resistance and produce mutations more abruptly and frequently.

SC: Do like working with the element of chance?

CD: Chance, indeterminancy, and constraints. I’m equal parts John Cage and Raymond Queneau with my methods. A recent album I’ m into is by the omnipotent Andrew Liles, “Fast Forward Through Time (Illusion Four).” This piece evolves (musically) in a way that I see my drawings evolve. Incidentally, Andrew has created a piece interpreting one of Panzee’s scores for an upcoming project I hope to realize as an LP.

SC: What do you use to draw on wood?

CD: My materials of choice are ballpoint pens and oil pencils. I’ve also done a few in color with Prismacolor pencils, but when you insert color you get other kinds of layers that I’m not as interested in. Right now, I’m making an effort to produce the work from a really basic level. What I’m talking about is exploring the origins of expression. That is what really kept me involved with working with Panzee, and working with her has allowed me to articulate and think about my work that way. So bringing in other things—paint or other media—brings in a subjectivity that I’m not interested in at the moment.

SC: Now I know where the dense, obsessive drawings come from, but what about the sound wave aspect?

CD: It all evolves from the same place. A lot of people assume that because they know I work with sound. I find it ironic, because it’s the first work I’ve done in a while where I wasn’t working with sound at all. I wanted to get away from it and explore drawing in a pure fashion. But it does resemble existent visual representations of sound.

SC: How is sound a factor in your work?

CD: I’m very immersed in all kinds of listening and producing. I’m not a musician. I take on sound as you would paint or drawing or other materials. It began with the sound of mark making. I set up an exercise for myself where I would record at 3pm for three minutes for about two years and have continued off and on up until now. I kept a log without any intentions. I like to have that kind of component in my work, where I do something for no other reason than I’m just curious. I wanted to get used to working with the microphone and using it like a camera, and one day I was in class and the students were drawing and I thought, wow, that’s an interesting sound. And it’s just like working with Panzee—it triggered a bang.