In November, I met up with artist Cheryl Goldsleger at her spacious studio, which is an addition to her home in Athens. Cheryl makes architecturally inspired work that utilizes encaustic and 3D printing to discuss issue of space—how we think about it and maneuver through it. I first encountered two of Cheryl’s large-scale works in the inaugural exhibition at the Zuckerman Museum of Art. She was recently included in “MAC@20 Part ll” at the McKinney Avenue Contemporary in Dallas [Nov. 8-Dec. 20], and “WHODUNIT?” a group show of works on paper at Cumberland Gallery in Nashville [Nov. 17, 2014-Jan. 10, 2015] and has a two-person show coming up this spring at C. Grimaldis Gallery in Baltimore.

We discussed the power of the female visionary drive, labyrinths, the theories of Gaston Bachelard, and the idea of location as an ever-changing concept. By incorporating technology into her works and using a unique arrangement of materials, Cheryl is approaching painting in a modernistic manner that is stirring and refreshing.

Sherri Caudell: What do you think about the concept of space and how we interact with it as humans?

Cheryl Goldsleger: As an artist, I’ve been attracted to depicting space because it’s something that we construct that tells a lot about us. As an example, think about towns or cities at different points in history. If you think of a village on the Nile in ancient Egypt, or of a medieval town, or London in the Middle Ages, or New York City or Tokyo today, those places are different because every culture has different needs. That’s talking about it on a large scale of how societies create spaces that work for them. Think of the Mesa Verde dwelling where one entered through the roof. That is fascinating to me. We do a similar thing on a personal level with our homes, offices, and personal space. A vase or a shard from a culture 2,000 years ago tells you something, but when you go to an archeological site and you walk through that space, it tells you so much more. How we interact with, organize, and use space is defined by us, but also defines us. I’m very aware of my own space and how it makes me feel.

SC: When thinking about imagined spaces, what would your ideal be?

CG: I like open, clean spaces that are good to work in—not something that’s cluttered. As I get ready for a show, right before the show, my studio feels very crowded with materials and new work. Everything’s everywhere—it’s totally full. But as soon as the work is off and gone, I can’t start new work until I clean and put things away and get reorganized.

SC: What kinds of materials are you currently working with?

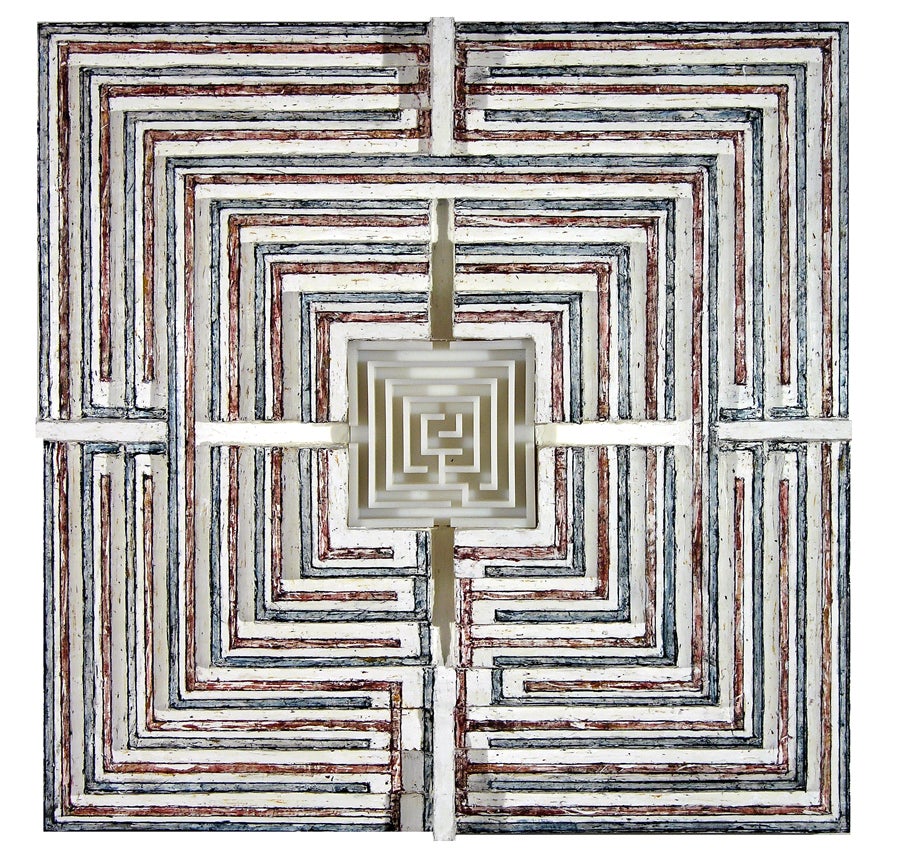

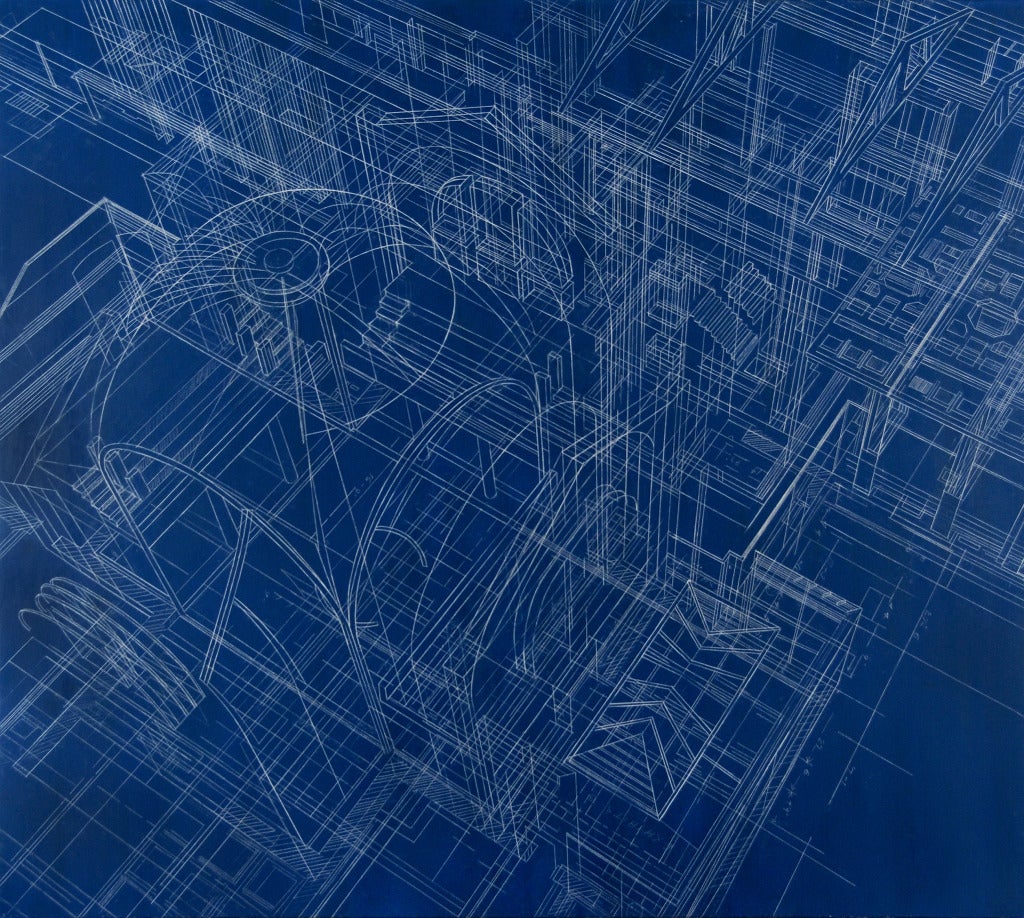

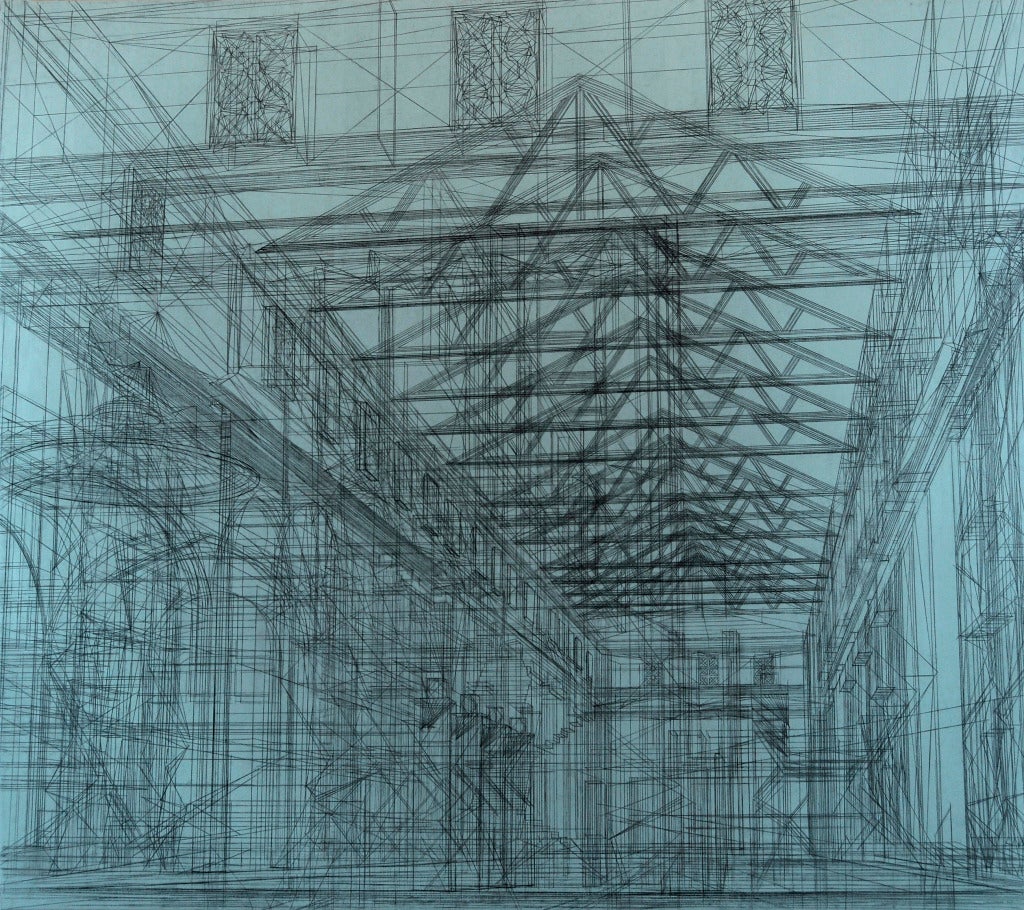

CG: I just finished a painting that’s in a show at the Art Center Sarasota called “Heated Exchange.” It features contemporary artists working in encaustic. My piece in the show is titled Release and includes 3D-printed forms embedded into an encaustic painting. I’m very excited about combining forms that I design and draw in a 3D modeling program and have fabricated in a 3D printer with encaustic, one of the oldest painting materials. Materials are important to me. I make my own encaustic, which is a blending of pigment and beeswax. It’s heated, and while it’s hot I work with it. I’ve worked with encaustic since the 1980s. I started using it because it allowed me to make the kind of marks that I wanted to make in painting. Recently, I finished a group of large-scale drawings, too. Because I wanted to work large and on colored grounds, I decided to draw on linen. So they are actually canvases, but I primed and prepped the canvases until they were as smooth a surface as good drawing paper.

SC: What are you drawing with?

CG: Chalks, charcoal, pencils, various tools.

SC: How did you go from drawing to incorporating three-dimensional elements into your paintings?

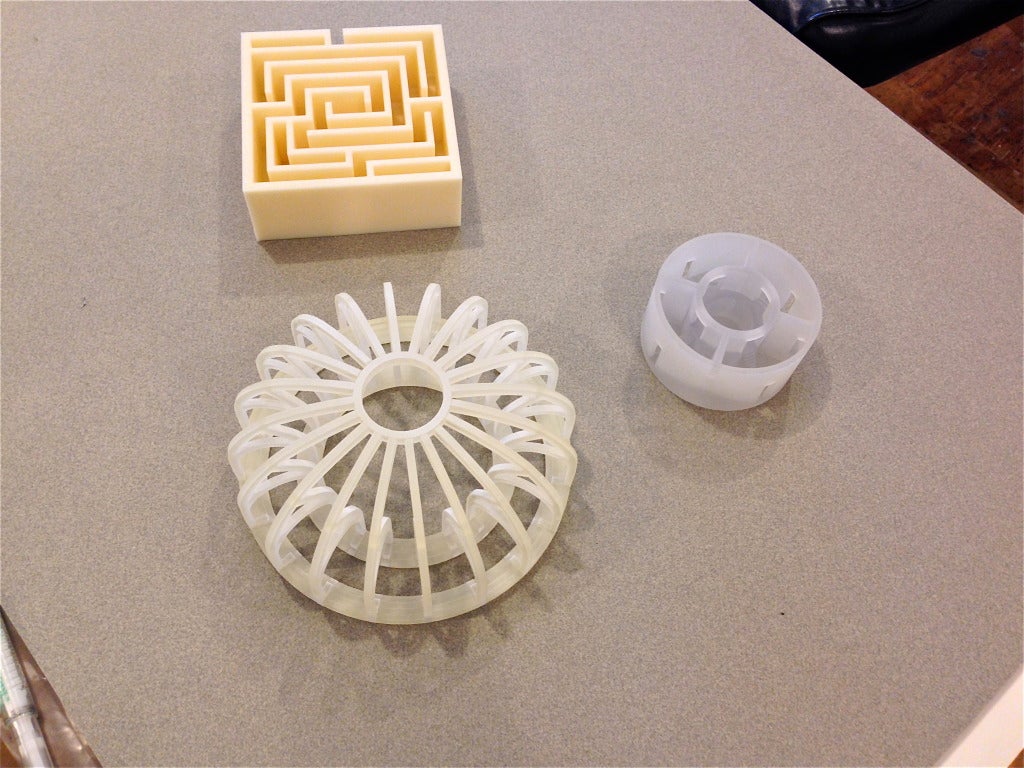

CG: My early drawings investigated spaces from different points of view using several different systems of drawing. I incorporated two-point perspective, isometric perspective, overviews, elevations, and overlays. That technical side of my work led people to encourage me to experiment with my ideas on computers. At first, the idea didn’t really appeal to me, but I became very interested when I learned about 3D modeling and 3D printing in 1999. 3D modeling incorporates multiple viewpoints, similar to my work at the time, and I thought that maybe I could use the technology in conjunction with my drawing and paintings and as a part of my work in general. My ideas about how to build the painting structure and how the 3D prototypes will integrate into the whole have grown enormously since my first paintings with embedded 3D forms. The forms in the painting Release deal with the idea of progression. The wax surfaces of my paintings have a physical presence and the computer-generated parts combine to make the paintings even more dimensional. This whole idea really fascinates me.

SC: Is that a 3D prototype over there on the table?

CG: Yes, this is a small labyrinth for a painting that will have eight different labyrinths embedded into it.

SC: Where does your interest in architecture stem from?

CG: It’s something that has always interested me. When I was a student in freshman drawing class, we would be expected to draw a model in the middle of the room and I would draw the entire room and the model. I didn’t leave her out. But the space is what really interested me. I started seeing what I was doing over and over again, and that the lines and planes were the aspects that really interested me, and I think I just distilled it.

SC: Do you look at works by famous iconic architects and/or at new architecture that’s being built?

CG: I look at architecture from all over and from every period. I make a point of going to see buildings that I’ve always wanted to see. I have books on the history of architecture and on individual periods and architects. What has been inspiring me lately are areas that are under construction—the unbuilt or the potential of a building. I love to see work sites or demolition sites.

SC: Are there certain needs that you think people have that aren’t being met by current architecture?

CG: I think that some of our needs are being met by current architecture but we are learning and finding better ways to meet needs while saving resources and the environment, and that is catalyzing many changes. One thing that appeals to me is walkable cities. I love being able to walk from one part of a city to another without having to use a car or bus. But, that may speak more about city planning.

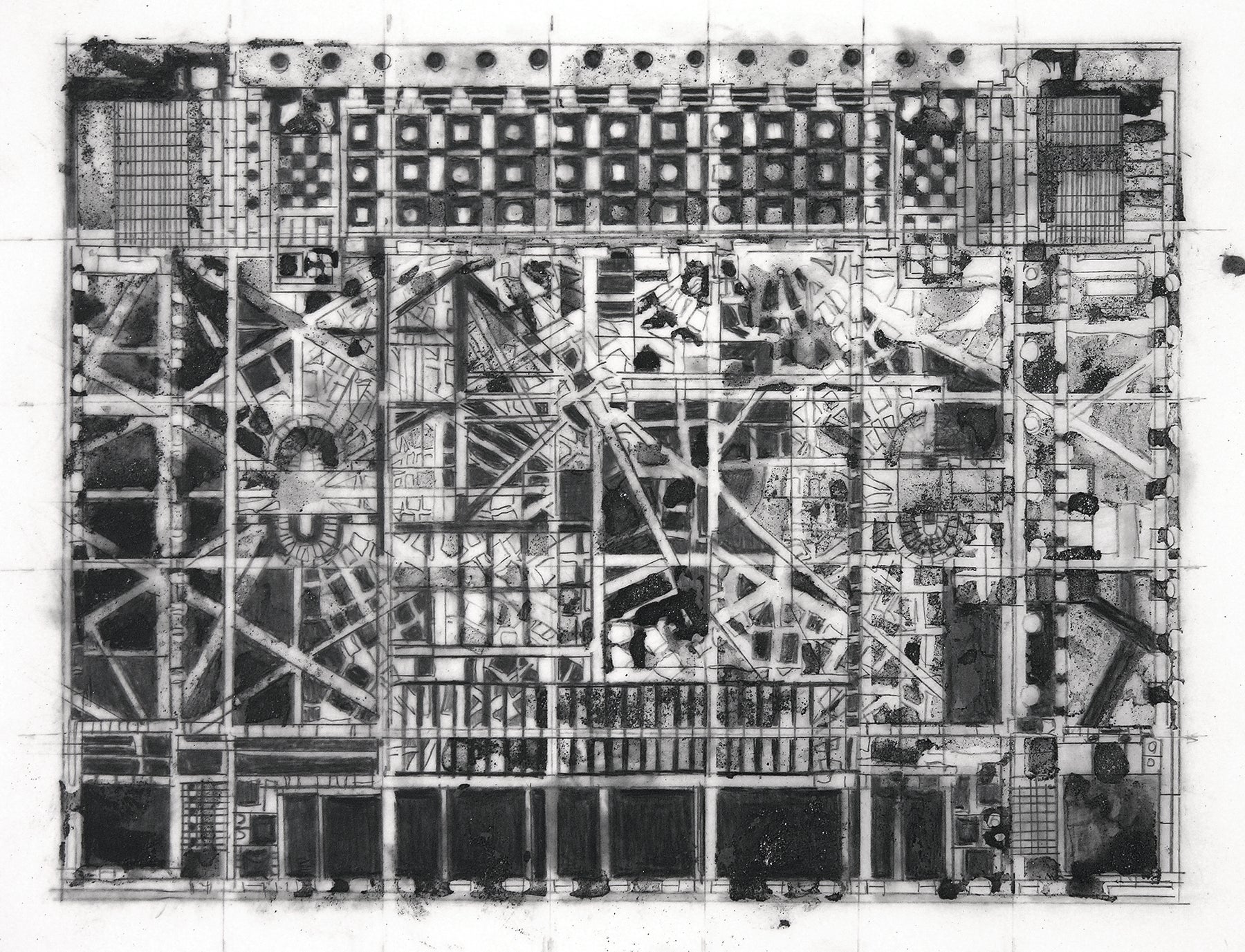

SC: Can you talk some about the conceptual ideas behind the project that you did at the National Academy of Sciences?

CG: The NAS project was an opportunity to work with the idea of an existing, very specific building, but to take it into an imagined plane. Gaston Bachelard writes in his book The Poetics of Space that there isn’t one space, that every space is different because every viewer is different and brings a different set of experiences to the space. You may love a place because it reminds you of positive things, while another person may not relate to it in the same way because it reminds them of other things or strikes them in a different way. It’s Bachelard’s idea of the space as a sort of a witness. I also think that individual rooms are like characters, and they become witnesses to the things that have gone on in them—accruing the events that have happened. This can happen in a physical way, like when a wall is scratched or damaged in a room, but I also imagine an unreal sense that everything that has happened is still happening in a space. The energy is all there and the space sort of absorbs it and holds it. I like the idea that the space actually isn’t permanent, that it is mutable.

SC: There’s something that draws me to mazes; I don’t know what it is. You can get lost, which is interesting. There’s an element of fear or wonder. You’re not guided through the space, but you kind of feel like you are. How do mazes and labyrinths fit into your work?

CG: Labyrinths and mazes actually have different definitions. A labyrinth is logical and you follow it and there are no dead ends. So when you go through a labyrinth you are going somewhere and you’re not going to go off course. A maze has dead ends. Both ideas interest me. When I began incorporating labyrinths into my work, I changed the viewer’s point of view again and emphasized the overall plan. I had spent some time in Italy and I remember going to Hadrian’s Villa, which is more of a small, sprawling town. It’s not a labyrinth, but there are different buildings where the black and white tile floor mosaics are still in existence. The designs are beautiful and I think I started to assimilate the idea of incorporating floor plans from looking at those mosaic floors. Also, I was doing research on English gardens, which often include labyrinths as a form of entertainment. What really does appeal to me is the sense of logic surrounding labyrinths, the sense of moving through a space, the sense that it all fits together. In some of my pieces, I’ve used labyrinths in combination with other things, so that they play off of other geometry or they evolve through the piece into other configurations.

SC: What do you want the viewer to take away from your work?

CG: I’ve had people tell me all sorts of things that they’ve seen or thought of after seeing my work. It is fascinating to hear what they have to say because most of the time their thoughts are very different from what motivated me to create a particular piece. I hope viewers will bring their own experiences and use those experiences to engage with the work. By entering it that way, they sort of move through it visually and they begin to understand it. I hope they get a feeling of what the space is to them and how they are an active participant building their own narrative without being told a specific one. I would like viewers to spend enough time to be inside of the piece and not just look at it from the outside. I want people to carve their way in and to realize that it’s almost never-ending.

SC: When I look at your work, I definitely feel like I go on a mental journey. I get lost and kind of find my way and then get lost and come back out again.

CG: It’s one of the reasons why I think so much about point of view. When the work deals with deep space, I’m very concerned about where I’m placing the viewer and what kind of analogies I’m making. Some of my pieces look like spaces that are institutional—not institutional in an academic way, but a formal large-scale space where people gather. I think of architecture as sort of the skeleton. I’ve been influenced by Umberto Eco’s writings, especially his novel The Name of the Rose and by the works of writer and poet Jorge Luis Borges. I’m looking at how I can convey the idea of searching for knowledge. No matter how much you know, there is always more to discover.

SC: You have a public art piece, which is a walkable labyrinth, installed at the Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International airport.

CG: Yes, it’s in Terminal A. I wanted to create an image that related to Atlanta and also to my own work. While I was doing research in the library, I saw the dissertation of a former colleague. It was on the early history of Atlanta. Inside was a reproduction of the very first map ever drawn of Atlanta. It was diagrammatic and I thought there could be a relationship to my work. And then I realized that the oldest part of Atlanta was exactly where Georgia State University, where I was working at the time, is located. It was wonderful to create an idea that had a personal relationship to where I went to work every day—right in that circle of streets. I decided to overlay a labyrinth with the map and integrate the two images. A labyrinth, like a map, is about travel and moving from one place to another. Most people who come to the airport are moving through it, since they’re either coming to the city or leaving it to go somewhere else or just changing planes.

SC: I’m also very interested in the “Utopia” exhibition that you did which dealt with women architects in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. What led you to that project?

CG: It was an interesting synthesis of ideas. I had just started doing 3D prototyping and Annette Cone-Skelton, the director of MOCA GA, came to my studio. She started talking about doing a show together. At the same time, I was discovering in my reading several women who had gotten involved in architecture at the time architecture first became a profession in the mid to late 1800s. It had transitioned from being a profession of tradesmen or craftsmen into a profession where design became important. Women were studying it and were being trained. Henry Frost, a Harvard architecture professor, opened the Cambridge School, an experimental school, to offer graduate training in architecture to women. One woman who was particularly impressive was Sophia Hayden, who was the first female to graduate from the four-year architecture program at MIT, and right out of graduate school, she won the competition to build the Women’s Building at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Her budget was less than half of the amount of money that she needed, but she still managed to build an enormous building on a grand scale. Painter Mary Cassatt painted one of the murals in one of the two tympanums above the main exhibition hall. It was fabulous, and I thought, “I just have to do something with this.” In many ways, the pieces I created only minimally hint at the sources of inspiration, but using their creations as a sort of jumping-off point to execute ideas and make compositions gave me an insight into the thinking that went into their works.

The exhibition was at MOCA, and then it traveled to the Morris Museum of Art in Augusta, and then on to the National Academy of Sciences. I’ve had two solo shows at the NAS now. It was a good experience and I learned so much. I know the women architects I focused on didn’t get all the commissions they could have, or build all the buildings they wanted to, but they set up their own practices, they specialized in things, they had unique ideas and did really good work. Like them, I want to make work based on contemplative ideas that deal with who we are, what we think about, and what we strive for.

Sherri Caudell is a poet and writer from Atlanta.

This project is supported by the Georgia Humanities Council and the National Endowment for the Humanities and through appropriations from the Georgia General Assembly.