Bryan Graf is a modern day J. Peterman, but instead of hunting for the finest perforated buckskin coats in Montana or vintage fabrics from the Chiang Mai River Market, he explores the places we typically drive past: the New Jersey swamps we see from the highway or the island interiors we ignore on the way to the beach. I met Bryan two years ago, as we both work at the Maine College of Art, but I did not see his work until an exhibition titled Swamp Thing at Bodega Gallery in Philadelphia last year. This was a look at spaces left behind, artifacts of suburban runoff, trickling down throughout the wetlands. For the duration of our friendship the majority of our conversations have centered on our mutual admiration for NHL hockey and the turnpikes and parkways of New Jersey. Even a stop by his studio typically results in more casual conversation, so we decided to get together on two different occasions—once in the studio, once on his back deck, in hopes that the exchange would not veer too far off the tracks.

____________________________________________________

Daniel Fuller: Do you believe in luck?

Bryan Graf: You put yourself in the right situation and stuff just works out. Barry Hannah, the writer, said there is a difference between luck and chance. Chance just happens to everybody every day. Luck comes from working your ass off.

DF: Are you a gambler at all?

BG: No, not at all.

DF: I was just wondering about this earlier this morning. We have talked a fair amount about cameras, about luck, and how you manipulate your film and materials. Every time you make a photograph there is a certain amount of gambling built in there.

BG: When I head down to L.B.I. [Long Beach Island] with family, I don’t sneak off to A.C. [Atlantic City] real quick when no one is looking. But the funny thing is that when I do gamble I only play roulette and I always bet on black.

DF: Just like Wesley Snipes!

BG: Exactly. I want to win a ton of money or lose absolutely everything. I have zero interest in gaining an extra five dollars.

DF: Casinos are the best businesses. I wish we could make museums more like casinos.

BG: We just need to get rid of all of the terrible paintings and sculpture from between 1920 [and] 1960. That specific forty years. Anything pre- and post-Duchamp. He was the first foothold of conceptual art, which is fine, but I disagree with his whole “what you think of the object.” Thinking about something does not make it art.

DF: He played with chance.

BG: I appreciate what he did, but I don’t enjoy spending time with what he did. Anti-aesthetic, repulsion, and throwing beauty and craft out the window—that’s not interesting to me. The questions he was asking and proposing were more interesting than the actual art. In the Whitney Biennial in 2008, whoever made those Duchamp replicas, well, Sherrie Levine already did that with those Walker Evans photographs.

DF: Sherrie Levine is still overlooked quite a bit ….

BG: Well, she worked in photography mostly, and photography is so fucking boring as a genre, it is just so traditional.

DF: How did you get into photography?

BG: Skateboarding. I started taking photos of my friends in New York while they were skating, just like everyone does. Just trying to make a trick someone landed actually look cool. I was using those plastic disposable point and shoot cameras. I used those for years.

DF: That is as based in luck as anything.

BG: They have a fixed shutter speed, and the flash never worked. I always had a ton of pictures that I would post all over the wall. And then I fell on my wrist too many times and was in a full-arm cast for six months, so I just started taking photos of random shit. Once I had surgery I stopped skating and started taking trips out on my own to take photos. Then I started reading John Szarkowski, who was the chief curator of the Department of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art. The first photography exhibition that they had at the institution was a Walker Evans show. Funnily enough I went into the city with my mom to see some of his prints hanging up there and I bought one of his books. And thought, holy shit! Walker Evans and Helmut Newton were my first influences.

DF: Call me crazy, but as of late, a large percentage of interesting photos are an advertisement of some sort. And almost definitely it is an ad for a fashion line.

BG: The first school I went to for photography was FIT [Fashion Institute of Technology, in New York], because my high school didn’t have facilities for us. I made photocopies of my shitty 4 x 6-inch prints at Kinko’s to fill out my college application. I went to FIT and dropped out three credits short of graduating. The first thing I learned … was how to light a model. There is a huge relationship between photography being this immediate thing and fashion being in-and-out, like that [snaps fingers]. They both have a lot in common in regards to production and dissemination.

DF: The photo major at FIT, is it entirely focused on lighting models?

BG: It was insanely technically. It was almost like going to school as a painter and learning what brush strokes are. There was more emphasis on what photography is technically, and how to perfect that, before we were allowed to shoot anything. We had to take photographs of orbs at different light angles and find the medium gray; we had to figure out how to duplicate film; test four different slide films and figure out how to make them look like each other. It was really very technical. A lot of what I do now, to a certain degree, I know what I’m going to get. Chance comes in with the materials I use, but the medium itself I know like the back of my hand. It’s just unconscious now.

DF: I have never seen a photograph of yours that could remotely be called figurative.

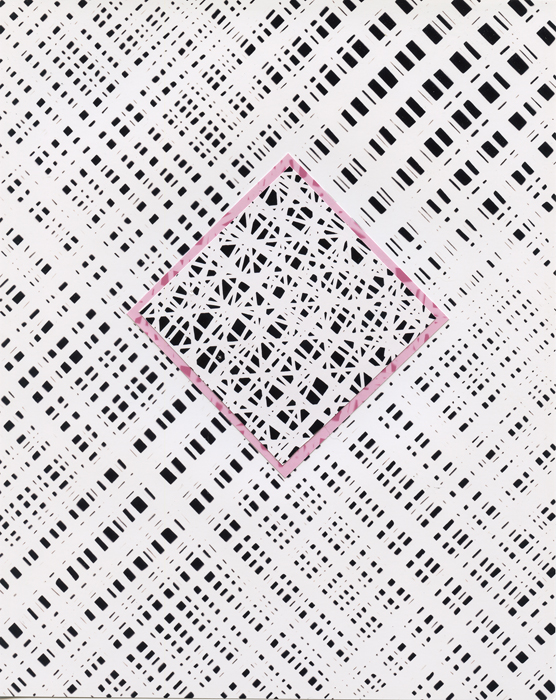

BG: But if you look around the studio right now, there are a number of photographs of patterns. And I think that has something to do with my time being immersed in pattern.

DF: The photo over there of the water has a human presence. It looks like it was taken through a windshield … like it was taken through a filter, and is by no means a straightforward landscape photo. I would never expect a straight-up landscape photo from you. There always has to be some semblance of a glitch that comes from a technical loophole or a hallucination.

BG: I think about that glitch too; I see it as an extension of the audience’s own psychology or projection of the version of what they are looking at. I think about photography and its modus operandi of being a transparent window onto the world, being this index of sorts. People still think of it as this thing that represents truth. So boring. The great thing about it is that it has this surface that is insanely representational and dumb, just like a language. It’s like talking to an infant. You say one babbly word and babies are off into their own little world.

DF: Couldn’t the same be said for all art? I am a video art guy but have such an aversion to media specificity. Look at grad programs. You go to the photo department and everyone is making prints, and in [the painting department] everyone is making sculpture. The one universal seems to be that everyone wants to be what they are not.

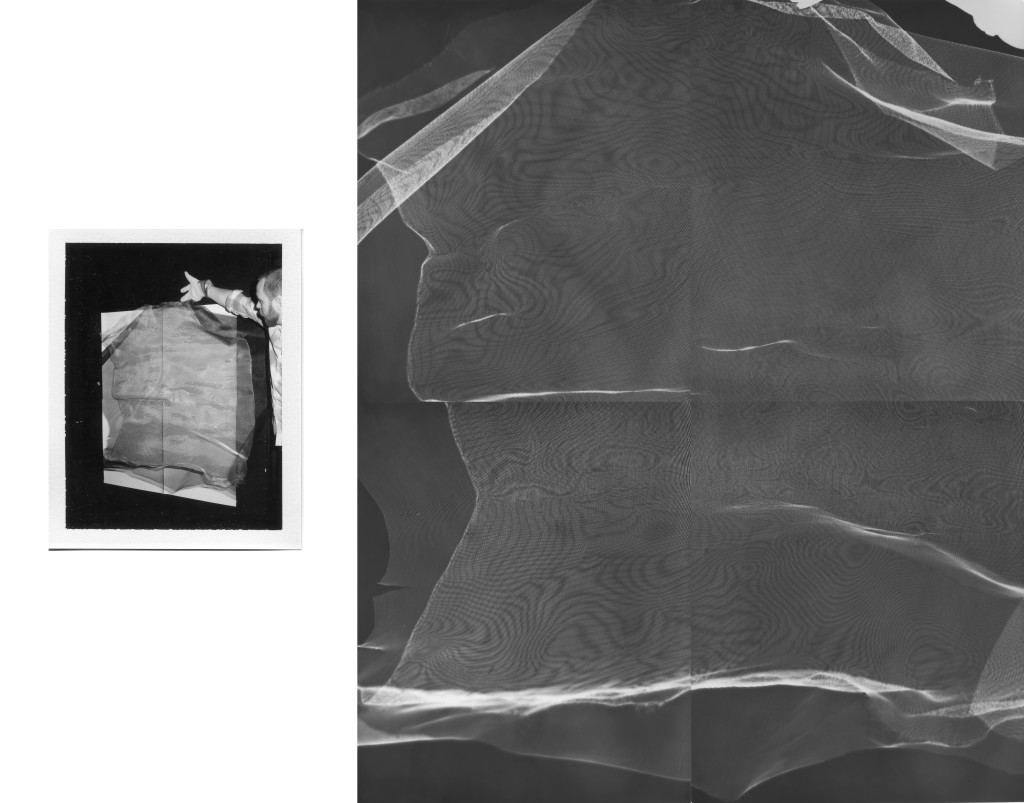

BG: I find that really dangerous for artists, too. I consider myself a photographer, because whatever I do, be it making a collage or a photogram, whatever specificity you want to get into; I will never pick up a paintbrush and make a mark. That gestural activity does not excite me. It’s not for me, I have an interest in boundaries and I have the photographic toolbox. Only sticking with that and seeing what I can possibly do with that is what’s interesting to me. Maybe it’s unbinding them and showing … the mechanics of how a photogram works to the audience. How to make a print or the shot/reverse shot stuff. My focus is on optical revenue. That is my game and my jam. I’m rigid in what I allow myself to do with materials, and there will never be a hand gesture. It has to be created by light or overall effect. The form is somewhat predetermined, and there are chance occurrences within that predetermined format, but it has to be within the photographic realm.

DF: As someone who was trained to be so technical, how did you get to a place of playing with the medium?

BG: I was in my second year at Yale and was doing a lot of scanning of appropriated materials. I was taking straight photographs, just doing everything. The more and more intense I got into the medium in grad school, the more I circled that one specific thing, and that showed me that I didn’t know a single thing about either art or photography. That’s when I started doing multiple things at once, as opposed to focusing on one idea. The more I work, the more I realize that ideas are kind of bullshit, that I don’t need ideas because I just need to work. Then you can figure it out from there. But if you go the other way it is like being a reverse curator, having an idea before knowing any of the artwork for the show. I believe more in absorption than I do [in] trying to project shit.

DF: But we all do that to some extent. We all bring our own personal histories and stories to the interpretation of art or of music or to a dance piece. I can look at the textile photo right there and get lost in it. I’m going to walk away with my own meaning, and I could have fifteen reasons [that] I’ve read it the way I have. And to me those 15 reasons trump your 21 reasons for making it. I have taken ownership of it.

BG: And that is super important. Once I put a work on the wall, I have nothing to do with it anymore. I do not matter one bit. The work does.

DF: I remember back when I was in college in Baltimore, there was a big scene of rappers and DJs who would make music on their laptops, and they would walk out on stage just to hit play. Then they would hit the bar just like everybody else. This is how the music was made, this is where it was made, replicating it live would be impossible, so the audience is going to experience it the same way the musician does. And if you want to chat about the music, here I am.

BG: At the end of day, teaching at an institution, when the students present their work—it is performance. And some of them don’t realize that. So they tell you what they do and how they made something, but it doesn’t matter. There needs to be some persuasion, just a little anchor to get people going. It’s like being a good storyteller. Start the audience off with just a little something and then let them finish the sentence.

DF: Can we talk about making things? The old American industrial way of making something …?

BG: Making something is important right? Making something is very important to bring up. I don’t care if anyone knows it, but I happen to make all of my art. But only to a degree, right? Some of my materials are prefabricated: the camera, the film, etc., but making the work, having my hands on each print, is important to me.

DF: Have you ever shot digital before?

BG: Let me show you this …. That is from a contact sheet of a picture I took when I was living on Peaks Island, Maine. I would take the ferry into town each day, writing thoughts in this journal while commuting. I’ve shot digital before, but I just like physical objects. Digital cameras and backs are such a huge investment, and it seems that photography is … one medium that is linked to commercial enterprise—more so than any other medium in the arts … well, maybe photography and video. Technological innovation or progression and photographic innovation are not the same thing; it should not be part of the same discussion. Just because there is something new that comes out for use by a broadcasting company doesn’t mean something else becomes obsolete—otherwise why would anyone look at a painting and still feel something? Just because you are using film for still photography somehow as this antique thing that is moving towards being obsolete is, well, it’s just stupid.

DF: I think of your work as having two tracks: the textual pieces/lattices and the landscape work. I wonder about your ability to go in between the two. It sometimes feels as though one is a progressive of the other, or that the lattices almost appear to be an extreme close-up of the landscapes. Whenever I visit your studio, which is not that often, but whenever I’ve noticed a pattern or assume that you are going to be working on one series—inevitably you are working away at the exact opposite.

BG: Honestly, that is something I want to do for myself. I just do not want to be bored or boring. I just cannot go into the studio and make the same things over and over. It would make me more money, but I don’t care about that. It’s about the day to day and being excited about what you are producing. W.G. Sebald wrote part of this great piece called The Rings of Saturn: “all we wish for is to be forgotten.” That erasure of name is really important to me, because my name on something doesn’t really matter to me. I don’t really give a shit if I’m dead in a day or in nine years from now, but my name on something does not matter. But that this thing still exists is what is really important to me.

DF: Work transcends, it lives on. Hopefully, of course. People come and go.

BG: Not to be corny, but when you watch Hitchcock’s Vertigo: This is where my life begins, this is where my life ends. She points to an inch-long section. That touches on a lot of what art should be, not the name or bravado of the artist.

DF: You live in Portland, Maine. And you have several galleries that you work with, but you continuously choose to live/work in a place that makes it less about you and more about the work.

BG: Going back to what we were talking about before with skateboarding, Gerhard Richter says that, “Art is the closest thing to religion.” I feel that way too. It is something I have to do. The most important thing is making work and if I’m not putting in that time, then I am not doing my job. Coming from a blue-collar background, I see it as a job. It is a realization [of] something greater and also a reminder that that thing you do is the other, it is not you, which I think is a very important line to draw in the sand. You need to respect your work, but you are not your work. I’ll go home and make dinner, but that is not my work.

DF: Do you clock in? Metaphorically or otherwise?

BG: Yes. Chuck Close said that: “Inspiration is for amateurs.” You make work and that makes things happen. Let’s head to Silly’s for some beers ….

This second part of the interview was done on Bryan’s back porch as we were serenaded throughout by a neighbor’s steel drum band.

DF: Is nature a scary thing for you? With your photographs of landscapes there is an uncertain gravity to them, and I wonder if your version of nature—being in New Jersey, right on the brink of New York, with the city continuously encroaching, how does that impact the way you view the environment? In some ways it is really cliché and I don’t like calling the landscape of that region post-industrial. That doesn’t actually fit and seems to be a tremendous misconception.

BG: That is a very American sentiment.

DF: Your work is very different from the reverential, awe-inspiring work of the photography of the American west. As opposed to [pulling] back and showing a panoramic view, you are getting very close …. Is nature this frightening thing that takes back from people?

BG: I have never consciously thought of it that way. As soon as you asked if it is scary, my first instinct is to laugh, but I do remember when I was a kid in the back of my parents’ house. We used to have woods back there, but now it is a bunch of condo buildings. A bunch of friends and my sister used to play in those woods, and one time a van pulled up next to us, the window rolled down, and a hand came out of it. We just heard, “Come here,” straight out of one of those After School Special movies, and we just took off running through the woods. I remember the woods being both a scary place and also a place that was safe. That’s a very real memory I have.

DF: After years of taking photographs in New Jersey, how have you seen the landscape change? With all of the new development, how has the physical landscape been altered? We have talked about this in the past, about nature fighting back. You can build as many cul-de-sacs as you want ….

BG: Well, nature is the most persistent thing there is, way more persistent than we are, it is omnipresent. Also, when you asked me if it was scary, I started thinking about Romanticism. Take Constable, whose paintings I find really beautiful, but he wasn’t as much of a landscape painter as he was a plein air painter. Whereas if you take a Frenchman like Courbet, he was actually out in nature, because in England there were pretty much no large land predators left, there were no bears. There were no large animals that were going to mow you down. I guess I prefer Courbet’s landscape paintings because he did them in plein air and he did them with a palette knife. He wasn’t attacking the canvas, because that is more of a painter’s painter thing to say, but he was very photographic in the way he painted, and what I mean by that is it was immediate. What he saw, he would get down so much. He would just throw paint around and see what was right in front of him. He was also notorious for carrying a gun. A deer would go by, [he would shoot it,] and he would call it mowing down nature. That was part of the sport of it. And in the valley of Ornans, where he grew up, is right where the majority of his life’s work was made.

DF: I guess that goes back to how you get right on top of what you shoot, and you are not going to [photograph from some] scenic overlook, but you are trekking into it.

BG: I’ve done that kind of photography for a while now. Going to school for photography can be a very provincial and numbing thing. I find that a lot of photographers, especially in undergrad, hang out with artists of different mediums and go to critiques with them. Their photos are very straight, very narrow, and then they go out and get shitfaced and they are … totally different persons than their pictures. Not that they are their art, because that is a slippery slope, but they need a little of that kinetic energy to sneak in. Photography has the ability to be antiseptic, especially within an academic setting, and I do find that so many people stay away from what is a little dangerous. As a teacher, I try to prevent that from happening. I try to show the students that painters have used photography for years, that sculptors have used it for years, that it has been a huge part of conceptual art. There are others things besides just a respect for the medium. Nothing will change the face of art the way that photography did, I truly, fully believe that. Having an instantly mimetic mediation of what you see and having that be validated by more than one person. Having a device that is just a practical tool of fiction form a kind of nonfictitious story, that adds to everything and then goes on to breathe a life of its own.

DF: You can never predict what you are going to shoot, before you go out there. It must be an intense moment for you, right when you see that thing, that piece of debris that is stuck in the mud or pushed up against a fence. Or, if it is a cool tree that hasn’t been altered or changed at all, there must be an adrenaline rush for you at that moment.

BG: Oh, absolutely. To go back to Courbet for just a moment: If you take all of his paintings, they were made where he grew up and where he lived; the landscape works have been pushed aside. There’s this great book titled Courbet and the Modern Landscape, where the curator pointed out that when Courbet made the painting The Artist’s Studio: A Real Allegory of a Seven Year Phase in My Artistic and Moral Life, in 1855, they show all of these characters around, but the one character who he is within the scene is the landscape painter. And he is looking directly at that canvas. A lot of what he painted was what he intimately knew, and then he left the region and would come back to make paintings over the course of his life. I have only been living in Maine for going on four years now, but I’m just starting to be able to make work about what I actually observe here. I can respond to things, but I feel that they are sucker shots. When I first got here I didn’t know the landscape that much. When I am in New Jersey or upstate New York or places that I am really drawn to, I have no clue what I am going to get when I go out. Sometimes I will go out for a week and not shoot a picture. Other times I will waste all my film shooting one little knuckle in a creek. I’m not going to try to explain it or think about why that is. I just want to wander around and then the rest of the shit comes later.

DF: When you lived in New Haven for grad school you would say that you lived in New Jersey and New Haven. Now that you have lived in Maine for [the] past four years you say that you live in New Jersey and in Maine. There is this tremendous connection to home, yet you don’t actually still live in New Jersey. I wonder how living in Maine affects how you shoot, what you shoot, and if it is a conscious thing? Do you feel like you are trying to shoot something different here, or is it all connected?

BG: I don’t know, but I have titles from papers that I carry around for a very long time. One of the more recent ones came from a weather report I heard last January. I was coming home from the studio really late at night and it was snowing. The only thing I heard on the weather report as the frequency was going in and out was [that] the person said, “moving across the interior,” and then it went back into crazy static noise. Then I just started thinking of images I have taken and then generating images that could go along with that snippet of a sentence, almost like curating in my head. I had two, three, four word blocks that I’ve been carrying around for a long time and they matter a lot—just as much as any images. It’s like my 2013 Yancey Richardson Gallery exhibition Broken Lattice. I’m working on a book with the same folks, Conveyor Arts, that will publish the Wildlife Analysis book for next spring, and they were curious if it was a complete body of work. I knew I couldn’t say yes. Maybe I should finish it, but I have only completed one body of work in my entire life and that was the Wildlife Analysis work. With that I felt that I’ve done everything I can do, this is getting boring.

DF: I was looking at your website today, and one thing that struck me was that a lot of the work crosses categories. At times I was wondering how an individual work ended up in this body of work and not over in another category.

BG: I purposely put some of the work that is in the Swamp Thing section of work in with the Broken Lattice work because I feel as though they both touch on similar ideas. Titles mean a lot to me. Words mean a lot, a hell of a lot. Show titles don’t say enough, nor does the press release allow you to really talk about your work. So, if you only get a little chance, especially when you are only making images, you only get a couple words and you better do something with it. So, in a way it’s a piece of persuasion. Like, Swamp Thing, it’s sort of funny, like the comic book thing, it is twisted and comical. It is literal, but also psychedelic. It’s like, you read comics as a teenager and then go smoke weed in these places and there are broken tapes and trash everywhere.

But some of the work I make from both Swamp Thing and Broken Lattice, it cross-pollinates. Something can be made as a result of one stream of thought, but then you realize it also works with another one. It is really important to differentiate them because it leads a viewer’s attention just via a title. And that is not to be cheeky or funny, but just being blunt. Just because a photograph is part of this stream of pictures does not mean it cannot be part of another stream of my work. The website is a mini-editing exercise.

DF: Do you go back into the website and edit or move work from series to series?

BG: I do it the first time and then just see how it will be. I think about it so much beforehand that if I didn’t leave it, I’d never post a photo. It takes me a long time. It is like that for sequencing for a show or sequencing for a book. Mel Bochner has some really great writing about photography, and his art in general is just too dense for me, I can’t get into it. But some of his more simple writing that he did for his more simple exercises, such as Mental Exercise: Estimating the Center Red Dot: Drawn First, Freehand Grey Dot: Drawn Last, Measured, 1972, he was trying to find the center of the page or trying to guess the width of something. One of the more poignant things he wrote was that the artwork you see is not bounded by the box, that it is the space between two images that matters the most. The friction they cause for still images.

DF: I know your Broken Lattice work pretty well at this point, but to an extent I still think of you as a landscape guy. When I was in your studio the other day, there was only one work that was a recognizable landscape and the rest was grid work and pieces that are abstract. Also, thinking about the color scheme of the Broken Lattice work, it feels very retro, like an homage to the 1970s. The color glows, it can be disorienting, it can feel as though it has been added to the paper later on. It seems as though there is color underneath the color.

BG: There is a push between it being a flat surface and a textured surface because [in] some of the Lattice work you saw in the studio the other day, the light source is so low that you get to see some of the grain in the paper.

DF: Your work is created by nature, it utilizes nature, but it does not feel natural. How much, if at all, are you able to choreograph the color? Is that influenced by any of the pre-shot decisions or manipulations, or is that entirely left up to chance?

BG: I am able to control the colors completely. I can control the colors no matter what, but I cannot control the form. Sometimes it takes one or two passes on the color enlarger before I figure out what color palette I want, but I know the color spectrum of light is totally different than that of paint. It is just like print. It’s R, G, B, C, M, Y, and I know what to do to get orange or pink or any of those in-between colors of the spectrum. But it takes a while because what I am starting off with in the darkroom is a flash that shows up red or black, it’s just ambient light. So, I start with that light source and then add on color filters, just using filter gels and strapping them on the flash. Then I do tests from different angles and distances. Angles and distance really determine what will happen to the paper itself with something on it. This is going to sound ridiculous, but if I have a sheet of paper on the ground and I put the flash with the blue filter on it, even with the level of the paper, I’ll get the grain of the paper. It will be a very dramatic, long form, but I’ll know the color. This is in complete darkness, but if I raise the flash to my knee and point it the same way, it will be a little more intense, it turns a little more red, a little yellow, and the color will be a lot more strong. So, it is really this strange language that I know, telling me what the color will be. This is all made in a big darkroom—like I’m making it in the middle of nowhere. Also, an old dictum of photography is that it is one of the mediums that defines content and form simultaneously, and I think that is total bullshit. I think it defines subject and form. Subject and content are completely different.

DF: When your work has been written about, I often see the word abstraction ….

BG: That’s a bullshit word.

DF: I think of abstraction as being almost arbitrary, but you have set up a very specific set of instructions for yourself. You know to hold the paper by your knee. These are not … random [sets] of conditions.

BG: I think abstract is the kind of word that artists feel safe using, because they feel like a curator will understand what they are trying to say. People will understand what they do, so it becomes a safety net. It is one of the words that is part of the canon to describe art. To say it is abstract just because it is not a two-dimensional representation of the three-dimensional form or object or thing or noun is just the wrong avenue. I have no one artistic place to go—I like Gang Starr and Slayer equally.

DF: Having been in your studio several times … of late, I was surprised at your choice of music—primarily earthy, ambient electronic music. In some ways it connects to your work because it is otherworldly, it takes you to another place. Like right now, we are drinking Genesee Cream Ale. This takes me back to the place I am from, to the place I care about the most. Your work is quite literally a visual representation of the places you care the most about.

BG: Can we add a playlist to this interview?

DF: Sounds good to me. We have talked a fair amount about your artistic influences, and they have primarily been folks like Blinky Palermo, Peter Doig, Luc Tuymans … suspiciously absent are any photographers.

BG: I am a self-identified photographer. Peter Doig especially, he ties everything into this world that he invented, like a musician does. Of course, he set it up through interviews or writings, like when Matthew Higgs did Peter Doig’s record collection, and so that has influenced people who like his work. I just think he really loves music, and it shows up in his paintings. And, in regards to that essay, you got to respect it. There are fewer people than more who can write about art and don’t try to prescribe a pill for the reader to swallow beforehand. I think it was Kitty Scott or Adrian Searle in their essay on Peter Doig—I cannot quote it directly—but they wrote a great essay starting with what was on the painting. The sky is melting, meaning it is raining … all the surface stuff.

DF: Let’s start wrapping up.

BG: Let’s go to Silly’s and get some beers.