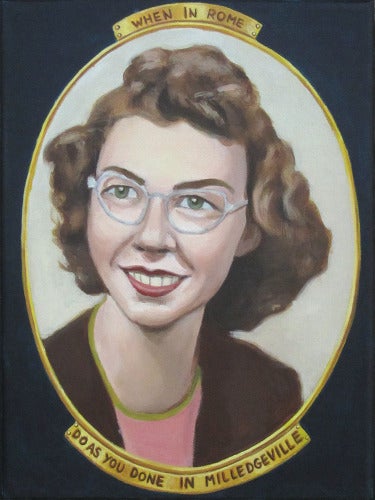

Ashley Anderson is no one-trick pony. His work ranges from lovely abstractions in the form of pixilated portraits to expertly drawn and super-detailed illustrations to large-scale installations that bring out the artist’s more conceptual side. Anderson’s work seems to pop up in a lot of places in Atlanta: wheat-pasted onto the storefront windows at Eyedrum, on T-shirts from Fallon Arrows, in exhibitions at Erikson Clock and Kibbee Gallery in artist Brooke Hatfield’s zine dedicated to Flannery O’Connor, and in design work for the band Little Tybee. While hanging out with Ashley, I found that he possesses a biting wit, a deep well of generosity and kindness, and a vast knowledge of the history of video games. “Ash” as he is known by his friends, is a genuinely nice person, but I was quick to learn that he takes his career as an artist very seriously and is a pro at setting professional boundaries—he is not to be underestimated. Ashley is a recent MINT Gallery Leap Year artist, and we met up at his studio at the Goat Farm, just as he was getting ready to move out and begin a new chapter in his artistic life.

Sherri Caudell: Tell me about being a participant in MINT Gallery’s Leap Year emerging artists mentorship program.

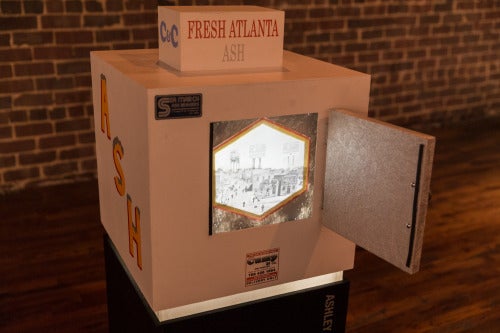

Ashley Anderson: I think everyone at MINT has been excellent about staying in touch and keeping everyone aware of what’s going on. Erica Jamison is always in touch with us. As a participant I got a show at Erikson Clock, a residency at the Hambidge Center, two mentors from the arts scene, and a studio at the Goat Farm. My mentors were Jiha Moon and Micah Stansell .We also received a stipend and memberships to different organizations in town. I took everything that I needed to work on the Erikson Clock show to the Hambidge Residency. It was exciting to just be able to work and not be very accessible. We have requirements for the program too. We did a public art project in collaboration with Flux Projects. We made light boxes that dealt in different ways with the burning of Atlanta. We even made a little takeaway zine. I made an ice vendor, like the ones you see at the gas station. But, when you opened the door it was lit from the inside and it was a two-sided gel transfer. I took a photo of Atlanta after it was burned down and superimposed onto it the AT-ATs and foot soldiers from the Battle of Hoth, which takes place in the Empire Strikes Back film. For the zine, I made a fake ad with a fake phone number, which you could call, and it took you to a customer service line that I had set up.

SC: Have you had any memorable studio visits lately?

AA: I recently had a studio visit with Jiha and one with Rebecca Dimling Cochran. The main points that I took away from my visit with Jiha is that I need to push more, not be so obvious with the way I’m treating my images, mess with materials a little more, and play with scale. The main thing I got from Rebecca was to consider the audience, and to make the work accessible at more points. So maybe have a few pieces that establish a context, and then have the rest of the pieces venture out a little further and get a little weirder. She also suggested not being in such a rush to put everything that I’m working on into a show, which is definitely a problem I always have. I always want to include a ton of stuff.

SC: What did you think about Jiha’s comments?

AA: I think she was right. I say “yes” to too many things. It’s been a death by a thousand cuts. I haven’t been able to be in the studio as much as I’ve wanted to. Because of the public art, working nearly full time, and then trying to produce stuff in the studio—I have had to be pretty firm in saying “no” to a lot of things. There’s been a positive impact from having to say “no” to everything because I’ve also had to be very firm about my market worth. So I’ve had people asking me to do album artwork or paint a mural. I always use two words that tend to scare most people off and that’s “contract” and “budget.” People do not like those words and that’s fine, because I don’t like working with people who don’t like those words.

(Photo: Sherri Caudell)

SC: So, it sounds like you’re learning how to streamline and prioritize for yourself.

AA: Yes, to prioritize, weigh options, and be prompt with my responses because that’s part of being a professional. But also just being able to say that I have too much going on and if I take on anything else it would be a disservice to myself and to whomever it is that I’m trying to help.

SC: What is your studio practice like?

AA: When I’m in the studio, I’ll be working on a painting for a little bit and then let that painting dry while I work on an ink gouache drawing, and while that’s drying maybe I’ll start working on building a panel or priming something.

SC: How has your experience of having a studio at the Goat Farm been?

AA: It’s been great. It was really good timing when I got into Leap Year because I had a studio in the house I was living in, and it rained for three months straight, so mold got on everything. I had to throw away 20 canvases. I knew a few people here before I moved my studio to the Goat Farm, like Brock Scott and his band Little Tybee. I’ve been doing stuff with them for a while. Right now we’re working on this big drawing, but I can’t talk about it too much. I also knew Allie Bashuk before she moved out here. I’ve gotten to know a few more folks, but just because of the times of day that I come out here, I’m not the most prone to social interaction. Not because I don’t want to meet people, but just because when I come here I go straight to the studio and get right to work. But, I leave my door open and I’ve had plenty of strangers walk by and say “Can I come in and look?,” and I say “Sure, that’s fine.”

SC: What have you learned from your other mentor Micah Stansell?

AA: He definitely has a different perspective because the kind of work that we do is so different. He does large-scale videos and a lot of stuff with photography, and I do these paintings of video game images. He’s been a great mentor. It’s nice to have had both Micah and Jiha; it’s kind of like having two parents with completely different backgrounds.

SC: What did you work on at the residency?

AA: These larger paintings of Ellen Ripley and these eye charts for the MINT Leap Year 2013-2014 show. I found an eye chart in the back of a game that interested me.

SC: Tell me about the Ellen Ripley paintings.

AA: I started these portraits almost immediately when I got in the studio. They’re all images of the character of Ellen Ripley from the movie Alien. They are sourced from different games based on the first two movies. Some are from the Japanese Nintendo game and some are from the arcade game, which I played a lot when I was a kid.

SC: Is that where your fascination with video games comes from?

AA: That’s where my knowledge of these games comes from, but my fascination is partly independent of the video game association. I really like pixelation.

SC: What do you enjoy about pixelation?

AA: It’s just pretty. It really is just like an innate attraction. I like a lot of Matisse’s work. I was working on some flower paintings and I was kind of hitting a wall as far as laying down the color in a way that was flat and not spatial, but that was still expressive somehow. I started looking at flower paintings and the ones that I kept running into that really touched on what I was going for were Matisse’s paintings. They are these flat shapes of color, but they are very specifically chosen, and they’re thoughtful. They’re also not perfectly flat and crisp. I hate vector art, so I don’t want anything that is that sharp.

SC: How does research fit into your art practice?

AA: I paint a little bit and then I do some research. I sat in here one day and just read the whole Wikipedia entry about the first Alien movie. I have this folder on my computer that is nothing but celebrities as they are depicted in games. They’re not very good likenesses because they are low resolution, but that’s what I like—the pixelation. There is a humorous aspect in that the game images are supposed to be Ripley and are also supposed to be Sigourney Weaver, who played the character in the films. But, they don’t look anything like Sigourney Weaver—they don’t look like anyone.

SC: So what do you think that element of visual ambiguity does for the viewer of your work?

AA: It probably makes it a little more anonymous. There is a way of combating that, which is providing a context through other means, such as titles. These paintings are less iconic unless you know who the subject is supposed to be. But, just as objects that are drawn and painted, I like to make something that’s nice to look at. I like to see what will happen each time I repeat the image. You can’t paint the same thing twice.

SC: Have you been working with any new materials lately?

AA: I’ve still been working with mostly paint, but I’ve been using ink a lot too. I’ve been doing these drawings with white ink on black paper. It’s basically one solid wash, but it’s going around things that are on the surface of the paper. I won’t even block off the areas; I’ll just do it all by hand. So you load your brush, draw a line across, and it’s at a slight angle so that it doesn’t leak straight down. It just kind of beads along the bottom edge of your mark, and then you come back and draw another line and that pulls that liquid down, and then you’re basically just guiding it down very gradually. These drawings are maybe 22 or so inches long and about 18 inches wide and take about 40 minutes to create.

SC: What is your view on artwork as a commodity?

AA: My goal is to sell enough work so that I don’t have to work at a shitty service job. I’m fine with it being a commodity. Going back to the whole idea of saying “no” to things, I’ve had people asking me to do illustration stuff for them. They’ll be like, “Can you design a tattoo for me?” I get asked that question all the time. And I say that my hourly rate is 60 dollars. That kind of separates the adults from the children and it saves me a lot of time. I just have a lot of stuff that I want to do and so if someone is going to take time away from that, it’s going to cost him or her. I’m over being cheap.

SC: Are you seeking out a gallery to represent you or are you just waiting to see what comes your way?

AA: I haven’t really thought about it because I’ve been so busy working on stuff. Most recently I got a proposal approved by Eyedrum for their “Existing Conditions” show. So I’m starting to get a little better at submitting proposals for projects. Before, I could never think of how proposals were applicable to what I was doing. The thing at Eyedrum changed that. As far as gallery representation, if someone thinks I’m a good artist and a good fit, I’m open to that conversation. But it would have to be the right fit and it would have to be worth my time and money. Also, I’ve gotten one proposal approved, and that gives me confidence to keep an eye out for other proposals. Because with that stuff, you write a budget and you put in an artist’s fee and you get paid for your work. It’s a hell of a thing to add to your CV. It’s certainly not enough to live off of, but it’s a nice way to fool around with the work in a different way.

SC: What did you create for “Existing Conditions”?

AA: I went to Eyedrum and looked at their new space. We were supposed to work with the building as it was. I saw these Visa and MasterCard stickers in the window of a café in one of the buildings Eyedrum now occupies. The actual images of those two credit card emblems are in the café window of the first Robocop arcade game. I had done little drawings of those but wasn’t satisfied with them. I thought, what if I finally scratched that edge of taking those signs and window decorations from the games and turned them into the actual thing. I could put them into a real context and just see how that felt. I had also wanted to teach myself how to wheat paste. So I wrote my proposal and said I will take images from different storefronts from different video games, blow them up to life size, and place them onto each of your five storefronts—and it was approved. The stuff that actually went on the windows was 180 square feet of static cling vinyl that you could put through a laser printer. Maxwell Sebastian and Kris Pilcher helped me do the entire wheat pasting. It took the three of us three hours.

SC: What are the best and worst things about being an artist?

AA: The worst thing is that no amount of schooling can prepare you for it and there’s a lot of luck involved. If you don’t have the right kind of family who supports what you do—which I am very fortunate to have—then it makes it really difficult to be firm in your decision to be an artist. There’s a really awesome interview with the painter Lucian Freud where he describes the whole project of being an artist as spending a lot of time not doing things so that you can do this thing without any real guarantee of it ever being successful. But, also there’s a lot of satisfaction that comes from it, because if you’re being authentic and you’re not trying to live out this cartoon of what it is to be an artist, a lot of the time you’re the only person with those particular ideas. So if you can make them happen, that’s really awesome. It takes you to neat places, but it isn’t easy. I can’t tell you how many manager jobs I’ve had to turn down because I’m not willing to give up my time. I mean I’m poorer than I could be, because if I weren’t spending the majority of my time on this stuff, I would be a fucking unpleasant person. I already am sometimes.

SC: You require the act of art making to kind of level everything out in your personal life.

AA: Yes, just so I don’t feel crazy. When I go home, my poor mom—I can’t stay for longer than 24 hours unless I have something with me to work on. I’ve carried a sketchpad with me almost every day since I was five years old.

SC: Do you have any advice for recent BFAs who maybe haven’t decided whether to go to graduate school and are also deciding how to go about being an artist?

AA: I didn’t go to graduate school. I might, that was another conversation I had with Jiha. I always think of this clip from ART21 with artist Shahzia Sikander. The only part of the interview that I remember is when she says, “What you need more than anything is time.” Personally, there’s a lot of popular media that I don’t keep up with. I’ve never watched Game of Thrones or Breaking Bad and I don’t care if I ever do, because each episode is a whole hour of your fucking life. I remember my professor Pat Walker saying that when you get out of school and everyone starts moving into their careers, they’re not going to understand that you can’t be as social as they are. Because their work, more often than not, they leave it somewhere. They’re not working more than one job, which is what you’re probably going to do for a long time before you are able to just do art. But, as you have a little more success and a little more success people will start to understand the value of that. I will leave you with a Winston Churchill quote, “Never give up.”

Sherri Caudell is a poet and writer from Atlanta.