One of the last shows I hosted as a DJ for the University of Georgia’s college radio station was called Crisis. For two hours every week during a late-night slot, my co-host and I transmitted a live, evolving soundscape sourced by physically digging through the station archives and from our weekly findings of experimental field recordings and noise on Bandcamp. The regular rotation included a field recording of an approaching thunderstorm, a chorus of frogs, Judy Dunaway’s Balloon Music, and the compositions of Alvin Lucier, Sun Ra, etc. We utilized two record players, two CD players, and a cassette deck simultaneously, along with the occasional in-studio, live performance. More than just radio DJs we treated the show as a performance, embodying weird characters as we curated our selections for broadcast. Together we created a beautiful, chaotic mess of sound to vanish over the airwaves at 26,000 watts.

WUOG 90.5 FM began its first broadcast with 3,200 watts on October 16, 1972 out of Memorial Hall in the center of the University of Georgia (UGA) campus in Athens, upgrading to 10,000 watts by 1977. A radio station’s reach is dependent on its wattage, or power, and most commercial stations broadcast around 100,000 watts, reaching about 100 square miles. Atlanta is home to two uniquely powerhouse college stations: WRAS 88.5 FM at Georgia State University and WREK Atlanta 91.1 FM at the Georgia Institute of Technology, each broadcasting at 100,000 watts. In early 1994 WUOG was boosted to its current reach of 26,000 watts covering a fifty-mile radius, broadcasting up into North and South Carolina in addition to the greater Athens area and towards the Atlanta suburbs. Its slogan, “26,000 watts and almost as many choices”, rings more than true, boasting over 8,016 albums digitally catalogued from the physical library.

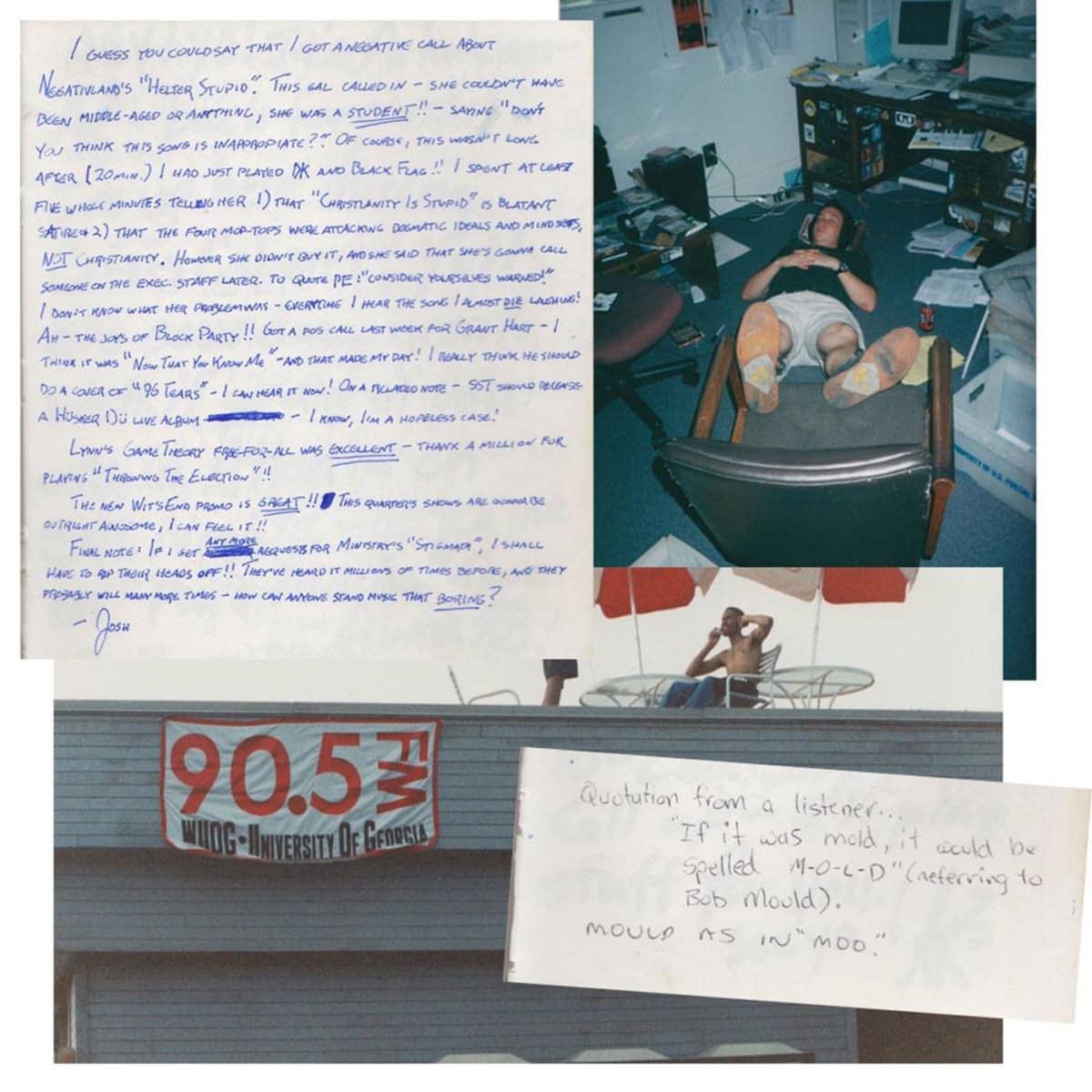

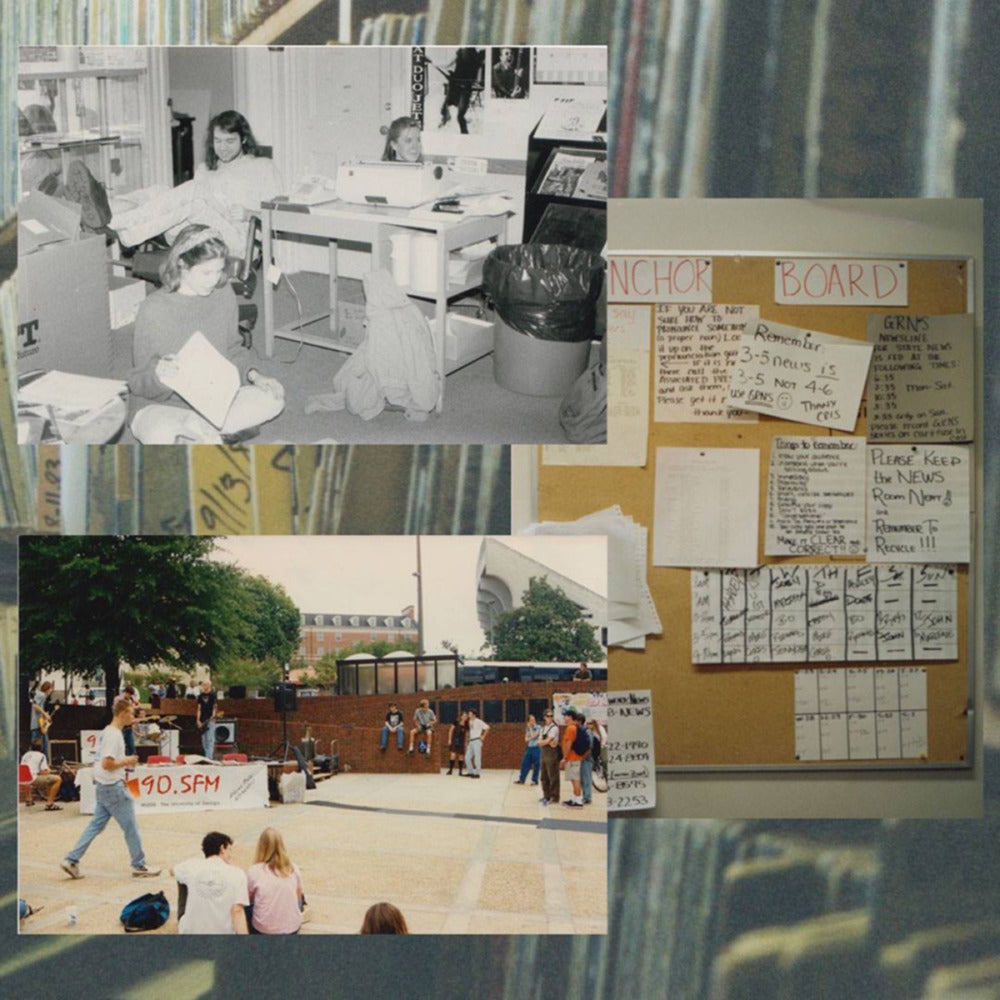

Some semesters I logged four or five hours a week in the booth in addition to attending staff meetings or serving on the student-run executive board. Most DJs contributed two hours a week, sticking to one specialty or talk show and a rotation shift. Being alone in the booth was cathartic. Overhead lights off, lamp in the corner on, and a glowing soundboard. Memories and mementos were splattered over the walls in sharpie, photographs demarking esteemed guests, legendary show run dates, and anonymous spastic drawings. Bands signed the wall of the music directors’ office after in-studio performances. One day in late 2018 we were suddenly prohibited from further writing on the door frames and walls; the Office of Student Affairs was going to be repainting our space.

WUOG has a fairly complex facility and broadcast system, making it a holdout among the vast network of college radio stations in the United States that have seen steady decline in recent decades. From the lobby, with its small stage and couches, the door to the broadcast booth sits to the right and the archives through a door on the left. The booth contains a control board, radio receiver, a desktop, landline phone, mic, two CD players, a cassette deck, two record players, and a mixer with an aux input. There is an adjoining room for talk shows, and another for producing in-studio, live recordings. Most of this equipment has been around for a decade and is maintained by the only station employee, a part-time retiree who checks on the antenna, performs weekly Emergency Alert System tests, and generally expresses disdain towards the school administration, often reminding DJs of the danger we could be in if the university ever decides not to renew the station’s license. A true comrade.

This broadcast architecture contains a vast, idiosyncratic visual that is typical among long- standing college radio stations with FCC noncommercial licenses. However, these kinds of college radio stations are becoming increasingly rare; the communal magic and aesthetic of alternative college radio has started its slow death. Being far left on the dial, as WRAS’s own slogan denotes, college stations are ever encroached upon by Christian music stations seeking a slightly higher frequency placement. Most college stations have been sold to Christian media groups like Educational Media Foundation, which operate K-LOVE stations across the country, or to local National Public Radio (NPR) affiliates like Georgia Public Broadcasting (GPB) in Atlanta. During the post-2008 recession era, hundreds of college radio stations were shut down or drastically cut—even among well-endowed private universities like Rice University in Houston and Vanderbilt University in Nashville. In 2011 Vanderbilt’s student-run station, WRVU Nashville, went off the air after the sale of its license to Nashville Public Radio for $3.3 million. It now operates as a student-run, online-only webcast, though not affiliated or monetarily supported by Vanderbilt. For Music City the loss of the only free-form, alternative radio station was devastating both to the generations of students involved in the programming and to their supportive community listeners.

WUOG is a community staple in Athens, one of the few positive bonds between the university and the local residents. Coming up on its fiftieth anniversary, it put much of the town’s now-famous acts on the national stage, helping to launch the careers of R.E.M., the B-52s, and Pylon. Decades of the town’s acclaimed local music scene—which can best be seen through documentaries like Athens, GA: Inside/Out (1980) and Athens, Georgia: Over/Under (2020)—would not have existed without the station and its commitment to noncommercial music. Particularly tied to this music scene of the 1980s is the work of self-taught artists in the region, including Howard Finster, highlighted in Athens, GA: Inside/Out for his collaboration with R.E.M. on their debut single, “Radio Free Europe” (1981) the music video for which was filmed in Finster’s home and folk art sculpture park Paradise Gardens in 1983. Talking Heads also came to visit the artist’s self-made sculpture garden and commissioned a painting for the cover of their 1985 album, Little Creatures. Athens is changing though, and it is rapidly losing the DIY spaces and scrappy venues that once welcomed WUOG’s bookings and events as well as other smaller touring acts, drag shows, and performances.

While WUOG continues to hang onto its terrestrial reach despite the university administration’s squeeze on off-campus events and after-hours DJ slots, the shutdown of neighboring stations has signaled dark roads ahead. In 2014 Georgia State University sold WRAS to Georgia Public Broadcasting for $150,000. The then-forty-three-year-old station had been in operation since 1971 at 100,000 watts and was the largest student-run station in the country. Programming on WRAS was handed over to GPB for fourteen hours a day during prime time. WRAS programming now only fills the 7pm to 5am time range through the analog station and GPB continues to pay the university fees that cover the station’s operating costs. The news programs managed by GPB are largely duplicate programs to those airing simultaneously on WABE 90.1 FM, Atlanta’s NPR station. As I sit in my car today and flip between those two stations, there’s only a mere five-second delay between them, except on one station I can, at least for now, expect the unexpected after the sun goes down.

This past summer, I spoke with WUOG alumni, Gerald M. Burris, who joined the station when he transferred to the university at the age of thirty, after years of a nontraditional college trajectory. Leading up to his eventual enrollment at UGA, Burris lived in Athens and began developing an affinity for its music scene. He told me, “I’d had a couple older, cooler friends in school who listened to WRAS back when ‘alternative music’ was still kind of a burgeoning thing. This was, you know, pre-Pitchfork, etc., and I found ‘college rock’ pretty inscrutable but nonetheless intriguing. That stuck with me, and when I moved to Athens, I did start listening to WUOG, and that whole world of important music started to open up.”

While some college stations open their doors to community stakeholders and DJs, WUOG and WRAS remain entirely student run and staffed, and this includes graduate student participation. One beloved DJ in Atlanta, Yoon Nam, ran the acclaimed Jet Lag program from 2006 until 2015—an entirely vinyl set of international psych, prog, vintage soundtracks, library music, and rare recordings from the 1960s and ’70s. Nam worked at WRAS for a total of eleven years while pursuing her Ph.D. in sixteenth- to seventeenth-century English literature, and eventually went on to co-host a monthly set, The Trip, at the Sound Table, a dance club and cocktail bar that was later demolished in 2020. While Nam can still be found DJing at venues throughout Atlanta, including the High Museum of Art and DIY artist space Hi-Lo Press, the closure of the Sound Table, one of the city’s premiere bars that prioritized live DJ sets, was tragic, mirroring the demise of the college radio stations that made careers like Nam’s possible. A multimillion-dollar development for a mixed-use midrise will replace the now-leveled Sound Table. Atlanta, like Athens, is spiraling with rapid development, erasing the landscapes where artists and weirdos can physically gather, create, and make discoveries.

College radio is a culture, and like most cultures, it’s ephemeral and embodied. It’s a space that cultivates a love for music discovery, production, and a cult of media and live performance. Among those invested in this space, there’s a strong sense of shared affinity and belonging to a broader network of artists with shared interests. We are all here for the same reasons whether or not we are here for the same bands. In addition to being a place where I could find fellow freaks, WUOG provided me with more professional skills than did four years of classes. I wrote short music reviews as a fledgling member of the local music staff, then learned to shoot and edit multi-cam videos of live performances as the digital media director. By the time I became general manager in 2018, I learned how to manage the budget for a nonprofit, negotiate with administration, and book shows with my fellow executive board members. Despite college radio’s decline in the last decade, the pandemic has provided this niche community a small moment of resurgence that may allow these stations to once again be recognized by their parent institutions as a necessary driver of creative exploration and community development. In speaking with WUOG’s current training director, Caroline Baston, she mentioned, “more people have gotten involved because of COVID-19. There have been a lot more sign-ups, and I think it’s because it’s harder to meet people with social restrictions, and the station offers an easy way to meet similar people.” It gives me a ray of hope to know that WUOG’s fiftieth anniversary next year will come during a time of renewed excitement. Perhaps it is not, as the Athens legend Michael Stipe forecast, “the end of the world as we know it.”

This essay is part of Burnaway’s yearlong series on Nodes and Networks.

Find out more about the three themes guiding the magazine’s publishing activities for the remainder of 2021 here.