The collective Speleogen is difficult to define, and in that challenge I found great interest. I recently met with some members of the collective at the home of artists and musicians Devin Brown, Mason Brown (no relation), and David Matysiak on a rainy but pleasant afternoon in July. The core group also includes Paige Adair, John Paul Floyd, Ingrid Magnuson, Meredith Kooi, Madeline Adams, and Jordan Noel.

These cross-disciplinary individuals have synthesized their talents and embarked on an art adventure. Borrowing from the term for cave exploring—spelunking—the artists explore underground landscapes, i.e., caves, to create group-sourced works that break new ground in their experience with the current art world and its limits. With all the moving parts they have to coordinate, this tribe remains cool and focused.

Sherri Caudell: Why did you guys feel the need to start Speleogen? Did you feel there was a lack of this type of collaborative art making in Atlanta art?

Devin Brown: One factor that animated Speleogen was that David, Mason, and I had primarily been musicians. We’ve been playing music together for like 20 years. But, even at the time that we were all playing in Hollow Stars, Mason and David each had other projects they were doing. David is a filmmaker, writer, and actor. Mason is a sound engineer and does Web design.

In some ways we had been pigeonholed, but the three of us, as well as everybody else we work with, have lots of other creative abilities and ambitions, and I felt like we weren’t utilizing them to their fullest potential. We weren’t doing performance art or any of the mixed-media stuff that we’re doing now. About a year and a half ago, I got to a point where I wanted to do something else. I created the structure of Speleogen and the working methodologies before we came up with the cave theme. I was interested in making systems that would help us keep producing work collaboratively over a long period of time.

David Matysiak: I like Speleogen because it’s about going to other locations to do art and using your body. It isn’t just sitting in one room and playing music or sitting at the computer. You explore and have an experience that you then try to recreate in an art piece. It’s about getting to a place and using what’s there.

SC: How does Speleogen’s art-making process work?

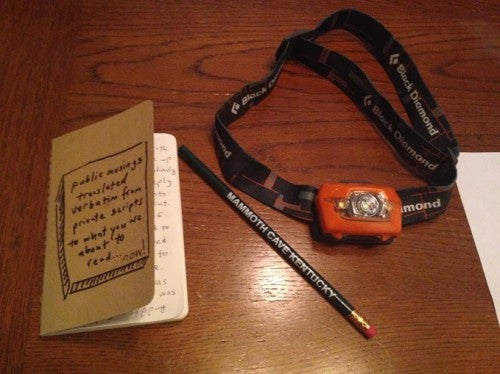

DB: I organize trips to cave sites, which we refer to as “excursions.” The team of assembled artists, who work in an array of media, including text, video, photography, sound, collage/assemblage, drawing, etc., travel to the designated site together and explore it. As of March 2014, Speleogen has made five excursions into the field. We have traveled to rough-and-tumble publicly accessible caves in northwest Georgia—Petty John’s Cave, tourist caves in Tennessee, and national landmarks in Kentucky. During the excursions, the artists “extract” materials they intend to use as the basis for future pieces by making field recordings, taking pictures, and shooting video.When the group returns home they upload and share with each other the media they have collected, using file-sharing programs like Google Drive.The artists have access to the media collected by all of the other participants. We highly encourage collaboration between artists, and many of the pieces we produce are authored collectively.

SC: You guys have formed a sort of super group.

DB: Yeah, and that was the entire point when I started this. In many ways, all of us have big ideas for things we want to do. I personally had gotten tired of not being able to execute projects because I lacked certain core competencies. I wanted to eliminate that problem for our community. Somebody in this group knows how to do it, whatever it is. Speleogen is a lab space for us, a training ground. Basically, I wanted this constellation of artists to know each other, to work together on things, to accomplish goals, to execute projects, and to see the finished work. We want people, like you, to become interested and ask us questions, so we can discuss the project—that’s how you create a community.

SC: Why did you decide to work in caves?

John Paul Floyd: The idea of exploring the unknown is what originally sparked my interest in caves. I had been exploring Boat Rock and wooded areas with my camera for quite some time, always searching for magical settings and beautiful light. The idea of photographing caves presented some interesting challenges. It’s hard to fully see the interior of a cave and you must bring your own light. This is not how I normally work photographically and therefore required some experimentation. I’m pleased with the original photographs but would like to improve and learn more about capturing these dark landscapes on film.

SC: Was there an element of fear of the unknown or were you embracing the unknown?

DM: Yeah, there’s a lot of fear, and I like that because it keeps you on your toes. It makes you really appreciative when you get through certain situations that you were afraid of. I like the fact that when you’re moving you’re not thinking about making art or anything. We are doing really tough stuff like climbing and utilizing ropes. I like the thought, too, that we weren’t the first beings to be playing music or creating sounds in those caves. You think of the cavemen, cavewomen, and cave animals. That to me is mind-blowing. Maybe when we’re there writing this music, it’s actually writing us, like the melodies live there and they use us as the vessel.

SC: What has it been like collaborating versus working as solo artists? How does the topic of social relations, dealing with different personality types, aesthetic approaches, and working methods come up?

JPF: I enjoy working with the group because of the surprises it offers. You never know what someone is thinking or how they’re going to respond to a challenge, and I love seeing the different ways people are inspired by the landscape.

DB: It’s very challenging. Basically BØATING, Synaesthesia, and Speleogen all started at the same time.

SC: Are those projects considered part of Speleogen?

DB: No, this is a question that we have to figure out. The projects are associated with each other if for no other reason than the same people are doing them and the aesthetic sensibility and working methodologies are the same for each project. They are all participatory. ROAM, a monthly audiozine of sonic collages crafted by sound scientists from across the globe, is another project. It’s curated by David, engineered by Mason, and designed by Jordan.

SC: So, you’re still figuring out if they’re just associated or if they’re an actual part of the collective’s work, sort of like branches?

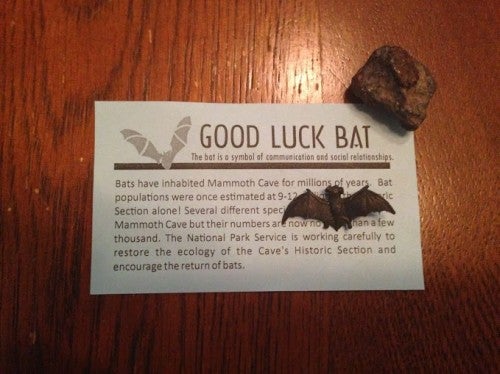

DB: I definitely think of it in the latter way, that they are a part of each other. They are not a part of Speleogen, which is just one manifestation of this other thing. The biggest challenge is that we’re doing something that is not very popular right now: being inclusive rather than exclusive. That can be hard for the audience to understand in terms of trying to figure out what the project is. It also creates issues when we have someone like Ingrid Magnuson, working with us. She’s a visual artist and makes physical pieces. We’ve never dealt with that kind of work as a group before and aren’t sure how it will fit in. Ingrid has made work from the Mammoth trip that you can hold; you could frame it and put it up if you wanted to. She was taking pictures, doing drawings, and collecting objects to make assemblages. Mason and I were running audio pretty much the whole time.

SC: How did each of you first become involved with Speleogen?

JPF: I had recently moved into the Short Street Home for Lost Boys during the summer of 2012, and shortly after Devin moved in and we began sharing stories. Our schedules were quite different, but we both woke early and began to share breakfasts and would take the early morning opportunities to discuss our adventures in the music world, the local art scene, and my forays into the wilderness. We came onto the idea that we were not completely satisfied with the current opportunities that Atlanta offered for showing creative endeavors and decided to do something about it. I shared that I was interested in traveling underground to explore the dark landscapes and he immediately began to imagine the possibilities of a new creative venue. It all seemed like new territory, both physically and conceptually. I think it was exactly what we needed.

Paige Adair: I came on board later. Devin and I met working in an archive, and I had been working on artwork on my own. As an archivist, I’m always sorting through material. After talking to Devin about the project, this seemed like a collective of people gathering material and putting somewhere for everyone to use. I’m really interested in narratives and different spaces, so it was a way for me to explore these places I hadn’t gone to yet. I’ve been doing a lot of collage work and video with Speleogen.

SC: I read that you spent the summer in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland through the Susan Cromwell Coslett Traveling Fellowship and were studying narrative gardens. How does narration play a role in your artwork?

PA: My work deals a lot with narrative and spaces and I was looking specifically at sites that had a history of narrative in the gardens. In Salzberg, Austria, there is Schloss Helbrunn, which is a trick garden full of games and water grottos conceived by Markus Sittikus von Hohenems. In Germany, I wanted to go to the “source,” the town where the Brothers Grimm wrote their collected tales, Kassel, Germany. There is a park there that has a monument to Hercules, and at Bergpark (Mountainpark) Wilhelmshöhe there are water and grotto elements. I felt like there must be something magical there.When Devin first started telling me about the excursions it reminded me of the way I set up that trip through Europe. I think there is a common thread in the way the trips were planned.

SC: What is your interest in narrative?

PA: In one of our first conversations I was looking at all of these fairytales that have caves and my work has been a lot about fragmented narratives and finding fairytales that are a little off or strange. Speleogen has plans to go to the Bell Witch Cave. That one is really interesting to me because there is already a narrative there about a ghost and a witch.

DB: There was a haunting at this place in the 19th century and it got some publicity and turned into a tourist destination. I’m really interested in cave tourism, which I wrote a poetical micro-essay about on the Speleogen site.

PA: I studied photographs of the first caving trips. I was excited about them and translated them into paintings combined with found imagery, including film stills and Victorian paintings and photographs from later trips. I went on my own trip to Ruby Falls and took some photographs. It just starts to build a language. This resulted in the piece A Portrait from the “Daughter of the Cave” series. I’m constantly screen-grabbing things that I’m looking at, a lot of which comes from my interest in female archetypes. There is a transformation that happens through all the media being combined, and it’s a fun and quirky way to connect and identify the cave as a place of transformation.

DB: This piece is exemplary of what Speleogen is supposed to do because it was a serious collaboration between several different people and every piece of it was composted or recycled or appropriated from a trip that we took. Then Paige added in other elements from outside. The piece is composed of a bunch of different elements, including the resource audio that we took in the cave itself, in Petty John’s, which Mason then manipulated. There’s music that Mason, David, and I are playing—that’s the soundtrack.

SC: I know you’ve been working with artist Meredith Kooi. What has she contributed to Speleogen?

DB: She went on the Ruby Falls trip and made a video piece, and she wrote an article about the collective for Bad At Sports.

SC: And Madeline Adams does mostly music for Speleogen, but has she branched out too?

DB: She’s an artist, a cartoonist, a writer, and a musician. Up to this point, her major contribution was a song that was kind of the Mammoth cave theme.

SC: David, I know you visited some caves in India. Did you go by yourself?

DM: No, I was working on a project with this organization called the Anchal Project. They are an organization out of Louisville, Kentucky, that was started to help women in the sex trade of India transition into more sustainable careers and trades, namely textiles.

SC: You were making a documentary?

DM: Yeah, I was filming and taking pictures for them. I went to caves that are from the 4th century B.C. that were made at different periods. The Jain, Hindu and Buddhist caves—you could spend weeks there.

DB: So Speleogen was international very early. We’d only been working for a few months when David went on that trip. He was writing to me from India and sending me all of this artwork. A lot of us are invested in this idea that there is not a difference between living your life and making art. They happen at the same time. And we’re all very opportunistic. So, he was doing a completely unrelated thing, but when he heard that he could get out there and visit caves, he knew it was related and important.

SC: Devin, what do you bring to Speleogen?

DB: The artwork that I do is creating the system. That’s my piece. Not just organizing trips and logistics but facilitating the making of the work. Which, in some cases, is me conceiving of and pitching things to people; getting them in dialogue with each other; setting up archiving systems so that everyone can get what they need; and explaining the philosophy of the project to everyone.

SC: Is there a name for a big umbrella collective that encompasses all of the projects you do, including Speleogen? Could you see at some point there being one website that contained all of the different projects, so a viewer would go to one central place and the artists could add projects and take projects away?

DB: We are aware that something is gestating and we can see the efficacy of having these relationships with each other. Something that is really important and has been from the very beginning is that we have tried really hard not to force them to do things that they’re not ready to do. We all talk about these issues a lot. But, the group has to figure it out and it’s got to be something that is an accurate representation of what all of us want to do.

SC: So it’s my understanding that it’s not important for all of the Speleogen members to remain constant. There’s a core group, but other people can come and go?

DB: Yes and no. There are people who work on the project who, if they were not involved, it would hurt the project. These contributors I need for their ideas and enthusiasm and the directions they’ll take. And the other parts are functional, so if they weren’t doing that stuff, the project wouldn’t happen. But, people do come in and out.

SC: How do you think that Atlanta’s art and music communities could connect in more ways?

DB: Collaborations have to happen in the beginning of a project for things to move in a new direction. So this idea of tacking something on at the end—I’m not saying that it isn’t cool or isn’t effective—but you’re going to get into a loop where it doesn’t change or grow very much. The music is not affecting what’s being created visually and vice versa. Instead, those things need to be threaded together at the beginning, to create a sense that everyone is contributing to this fabric and everything is interwoven. We’ve all been striving for this idea of seamlessness. We’re going to do this with the BØATING show. Everything is considered, in terms of how the space is set up, what’s in it, and where people sit, and how everything contributes to an overall feeling. I think there is a lot of collaborative work going on in Atlanta. But because we were in the music scene, we didn’t quite know how to join in.

SC: Where do you think Speleogen fits into the contemporary art world and the dialogue surrounding it?

DB: Speleogen could be considered an example of collaborative or relational aesthetics in the mode of critics like Nicolas Bourriaud. I didn’t even know such a discipline existed until Meredith introduced me to these concepts and put our working practices into dialogue with this theory. Later, Meredith invited Speleogen to present our work to a class she was teaching that had a unit on collaboration in art practice. In preparation for that discussion we read pieces by critics and academics fielding this topic from various angles. It was the first I’d heard of it and it was terribly interesting. But I really must admit: I don’t know a great deal about the contemporary art world other than what I read in magazines and books and on art blogs and what I see in local galleries and other spaces when I’m traveling, which is increasingly seldom lately. I did not go to art school, I do not have an MFA, and I do not have plans to get one.

However I and my compatriots construe our relationships with the art world depends less upon looking “out there” and more upon cultivating what we are doing right here. That doesn’t mean we have blinders on. Our tastes and interests are wide, eclectic, and in some cases even academic. Some of us have more prolonged or official relationships with the art world as an institution than do others. Paige has an MFA, as does Meredith, who is also working on a PhD at Emory University’s Graduate Institute of Liberal Arts. I was briefly in this program and met Meredith there. I lived in Brooklyn for a few years after college, and I went to art shows and experimental theater performances and film screenings when I had time and could afford it. Perhaps the single greatest thing I took away from that experience was the idea that for some people, in this case New Yorkers, art was not special or precious in the sense of being rare. It’s part of the everyday fabric of the city.

SC: Speleogen’s work is very difficult to categorize, which makes it really interesting.

DB: I consider myself marginal.

SC: An outsider artist, in a way?

DB: I don’t know. BØATING feels to me like outsider art in the sense that we really don’t know what we’re doing. In certain cases, we’ve forced ourselves to not be proficient technically: through playing instruments we don’t know how to play, by severely restricting the player’s freedom, or in Mason’s case, basically deconstructing his instrument so that it’s almost Cubist.

SC: Have you looked at any similar collectives for inspiration?

DB: The biggest influence was the New York School. I wrote an article about this, for BURNAWAY actually. It was about “The Club” that was formed by the sculptor Philip Pavia. World War II pushed artists like Duchamp, de Kooning and others out of Europe, and they moved to New York. Pavia got all these people together and they had a lecture series, they had meetings where they would discuss aesthetics, they had performances in this space. There were musicians, poets, art critics, artists, and filmmakers who attended—it was all over the map.

SC: Are you interested in looking at art that’s going on now, or not so much?

DB: Certainly, I am. We live in a certain place, which has access to certain types of art culture but not others. I work a full-time job, so this is not my career. And that limits the amount of time that I can spend doing research. One of the things I struggle with is that I would feel far more comfortable being more knowledgeable about what I’m doing. Unfortunately, I can’t do both the research and the work most of the time—it’s a choice.

SC: If you guys were going to show your work in a gallery setting, what do you think that would look like? Would it be a multimedia experience?

DB: All of our work so far is digital and has been displayed exclusively for free on the Web. We have discussed showing our work in a gallery since the project’s inception and I’m interested in exploring as many different presentation scenarios as possible. I don’t like hierarchies of importance. It shouldn’t be the type of thing where the music is more important than the visuals which is more important than the food being served, etc. The person who is experiencing the thing gets to make those decisions. We’re not dictating what you’re supposed to be hearing, seeing, or thinking about. It’s supposed to envelop you and provide conduits for experience, but you have to decide how you’re going to interact with it.

MB: Yeah, it would be a more immersive experience, rather than just a bunch of stuff on a wall.

SC: So it would have elements like sound, and projections and artifacts?

DB: I would like for it to be very controlled and the kind of space where there can be artwork and performances. I like the idea of maybe replicating in some way the feeling of being on these cave tours;not a carbon copy, but basically using the idea that you have a limited amount of time in the space and you are being guided by people through it. When the project began, we were publishing new pieces weekly for months. It was piece oriented. Now we have moved to a model that is more excursion oriented. I started thinking about the trips in terms of major focuses and themes. So Ruby Falls was about hyperreality and tourism. Mammoth is a totally different space because it’s a national park, so pedagogy and history are really important. Science, in terms of hard science is really important.

SC: How does Speleogen relate to the idea of commerce—selling yourselves as artists and selling your work?

DB: We all know that a painting or a sculpture possesses a different kind of monetary value than a video or a sound piece. No one feels weird about charging hundreds of dollars for a painting or even a photographic print, but can Mason do something like that with a sound piece? Would people consider spending $300 on a sound or a video piece of Paige’s? Even though it’s very obvious that we know we are in the 21st century and know what sound and video are, they don’t inspire the same level of awe as physical work. If our work never goes in a gallery, that’s okay. It doesn’t need to be legitimized by a gallery. That’s one reason it’s a big deal to have a conversation like this, because in our year of activity this is only the second time that anybody has offered to talk to us and write about it. I think there are some major things to talk about in terms of the commercial or noncommercial aspects of people’s work and who your audience is.

SC: Do you have a target audience?

DB: My target audience is the artists that I’m collaborating with. I know I’ve done my job right when they’re excited about doing the project that I set up. They are my ideal audience, because they have similar values as me, I respect them intellectually, I don’t have to pander to them, and I can give them challenging things to work on and they will rise to the occasion. My view from this comes not from an adversarial role with an audience; it comes from being in situations in bands where we were getting stuck because people were concerned about how something would be perceived.—how do you sell it?

SC: So you’re taking these pressures away and just focusing on the experience. You’re not worried about making money from this venture.

DB: Right and these are political statements. If you give your art away for free, you’re telling the world “We’re not doing this whole commerce thing right now.” You begin to think about the relationship to your work differently.

PA: Can that be sustained?

DB: Probably not.

SC: You need funding for your projects.

DB: Oh yeah. Mammoth was the biggest thing we’ve done in terms of the amount of time spent on site, the amount of material collected, the most ambitious theme, and in what we want the end product to look like. But, it was done relatively cheaply. We could all drive there, the tours didn’t cost that much money, we were staying with friends and in some cases they were cooking for us. So that was helping to mitigate the cost. But, there are other projects that we want to do that would cost thousands of dollars. Projects where we’ve got to fly to the location, stay in hotels, and feed people. Plus all the preparatory work and all the equipment we would have to buy. So, in the future, if we decide that we want to do these bigger projects, there will have to be some financial backing or it won’t happen.

SC: Tell me about the event Shore Leave A Protean Revel: A durational performance by Paige Adair and BØATING coming up on August 2nd at Big House on Ponce.

MB: The show is probably 80 percent improvised. It’ll be a sort of variety show with a lot of different things happening at the same time.

PA: I’ve got a multichannel video installation. I do have the art background with the MFA, so for me one reason working with this group was so attractive is that I’ve found myself wanting to do large-scale things, but it’s hard with just me. You need an army. You need people who are specialized in sound engineering and specialized in performance stuff, so for me this is exciting because it’s a way to utilize everybody else’s brains and power to work out these ideas that I’ve been thinking about.

SC: Can you talk some about your excursion to Mammoth and that body of work?

DB: I have a theory; I think that Mammoth is so physically big and imposing, and it is so difficult to talk about that basically any attempt to represent it is a failure. The cave does lend itself to being marked upon, rather than just talked about. Which are two different things. So literally the cave has carvings and graffiti.

DM: I created a video piece that is entitled the Unfortunate Fate of Floyd Collins, which marries a 1959 newscast about the actual Collins tragedy with sound and visual elements from the Speleogen excursion to Mammoth Cave. You can feel Collins interfering with our transmission, perhaps channeling ancient spirit energy in the caves—a restless spirit haunting his own historical retellings over time.

SC: What’s next for Speleogen?

DB:. We’ve talked about going to Bell Witch, which is in Adams, Tennessee. We’re talking about going to Luray Caverns, which is in Virginia and is where the Great Stalacpipe Organ is. We would compose a site-specific piece of music and a performance to go along with it that would happen there. David may be going to Panama to do some caving soon. We might go to Mexico with some friends in the wintertime and there are some caving opportunities there. I would really like to go to Carlsbad Caverns National Park.

Sherri Caudell, a poet and writer from Atlanta, is the poetry editor of Loose Change magazine, published by WonderRoot.