Back in October, the Speed Art Museum in Louisville hosted the symposium Southern Symbols: Remembering Our Past and Envisioning Our Future, held in conjunction with the exhibition “Southern Accent: Seeking the American South in Contemporary Art.” [Read more about the symposium here.] I recently had the opportunity to sit down with Miranda Lash, curator of contemporary art at the Speed and co-organizer of the exhibition, to discuss the symposium, Southern symbols in contemporary American society, and the role artists can play in conversations about memory and meaning. Before becoming curator of contemporary art at the Speed Art Museum, Lash was founding curator of modern and contemporary art the New Orleans Museum of Art.

Jessica Oberdick: Can you briefly introduce the symposium and describe its connections to the “Southern Accent” exhibition at the Speed, and to current events in the US more generally?

Miranda Lash: The exhibition “Southern Accent” that I worked on with Trevor Schoonmaker came together as a concept to deal with the complicated way in which we understand the American South. We started talking about it 4 years ago, and even then, we saw the South as both a culturally rich and politically evolving concept, and we wanted to bring the loaded emotions that can accompany Confederate symbols into the discussion. So even well before the shooting at the Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, we were looking at the work of Sonya Clark, for example, and Hank Willis Thomas and William Cordova, who directly address Confederate flags and monuments. The large Confederate memorial outside the Speed Art Museum was removed a year ago, and a number of cities have reevaluated their stance towards Confederate symbols. In the wake of these heightened levels of discussions and monument removals, we thought it would be worth supplementing “Southern Accent” with a public discussion on how we want to remember the past and think about the future of the South.

We acknowledge that the past has to be retold in some way, so we invited historians to address the public, to provide context to memorials and monuments associated with the Confederacy, and also give them tools to reconsider how we might memorialize the past. Even if cities are deciding in some cases to remove their Confederate monuments and symbols, every city still needs to grapple with how those stories should be told. We also wanted to invite artists into the discussion, because artists bring a creative perspective, and they can bring suggestions and thoughts for how to move forward and how to tell the stories.

We also wanted to remind people that the legacy of slavery and racial violence is not just confined to the South, though the South plays a large role in it. So, how do we want to tangle with those issues nationally?

JO: I’ve been reading a lot about this idea of “Southern unity” and the notion we’ve inherited of the South being very much unified against the North, which is not necessarily true. A lot of people from the South fought for the Union, for example, and vice versa. The “Southern Accent” exhibition considers the South more as a feeling and less as a strictly defined geographic region. Do you think the monuments and symbols contribute to this idea of “imagined Southern unity” and contribute to the idea of the South versus the North?

ML: It’s absolutely necessary to look at when these monuments were erected. Kentucky is a great example, in the sense that Kentucky was not aligned with the Confederacy until after the surrender. We were a border state, we had slaves here, but we did not officially align with the Confederacy until it became clear that it would be economically profitable to participate in rebuilding the South after the war. The memorials that went up regarding the Confederacy, just like the one outside the Speed, were erected in the 20th century, decades after the Civil War. As many scholars note, it wasn’t an immediate response of grief; they went up during the Jim Crow era as rights were being repealed following Reconstruction, to remind blacks that even though the South lost the Civil War, white people were still in charge.

Confederate monuments are not limited to the geographical South. There are Confederate monuments in Arizona, and you will see Confederate flags flying in Minnesota. We wanted to talk about the South as an emotional concept rather than a geographical one, because affiliation with Southern identity is not checked at the Mason Dixon Line; it’s good to discuss how it is a fluid concept, constantly evolving. I really prefer to describe Southern as a verb rather than a noun, as in something that is being enacted and re-performed on a daily basis. The meaning shifts over time. Trevor and I had no idea when we put “Southern Accent” together that the monuments in New Orleans would come down while we were installing it at the Speed Art Museum. There’s a video piece by William Cordova depicting the Robert E. Lee monument in New Orleans, but we never thought that I would be hanging labels for the show as that monument was coming down. I think it is tragic that it took acts of violence to precipitate these discussions, but here we are. The South is an emotional concept with layers and layers of complexity, which is why I felt a discussion was important, and that art is the best format for this type of discussion. Art is open-ended. It doesn’t prescribe how you should feel, it is not an edict. So, disclaimer, we aren’t telling anyone what they should do; we are just providing context, through images, about what has happened and what could happen in the future.

JO: What sort of roles can artists play in reflecting or shaping these narratives around Southern symbols?

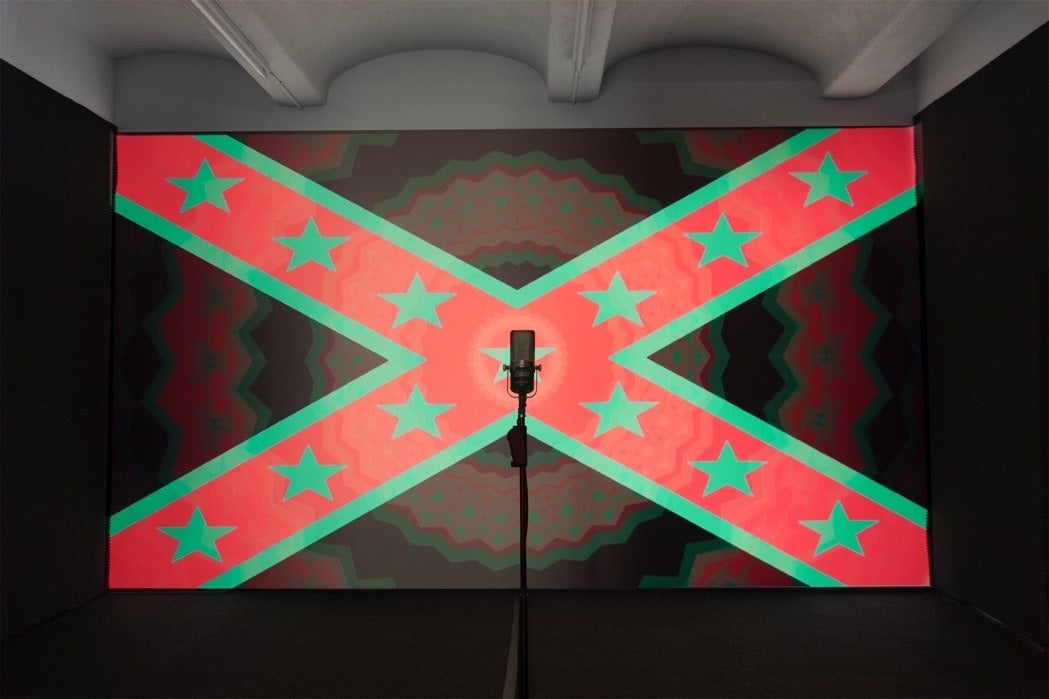

ML: I think Hank Willis Thomas and Sonya Clark are great examples. In his piece Black Righteous Space: Southern Edition, Thomas created a Confederate flag in red, green and black, the colors of the Pan African Liberation Movement. That is an immediate visual cue that symbols are malleable and symbols can change. There was a microphone in the center of the room, and any member of the public could use it, and thanks to a computer program, the design of the flag will vibrate and change. It just reminds me that it is the accumulated effort of individuals that keep these symbols in place. When change is desired, change over time can be possible and that is one of the themes we try to put forward through historical images.

Sonya Clark’s piece is an unraveling of the Confederate flag, but it is a labor intensive, slow process. Even though we worked on it (during her performance at the Speed) for two to three hours, and only a portion of the flag was unraveled, which is a reminder that this is a process that takes time, changes in social perception take time. I think art, through these actions, can engage people in this discussion by perhaps inspiring them to think differently. The artist Mel Chin once described art as a catalyst that inspires you to think, not what to think. I think people want to open up the discussion but they do not want to be told what to do.

JO: Can you say more about the artists and scholars who participated in Southern Symbols and briefly outline what they spoke about?

ML: Historian Catherine Clinton was the moderator of the morning session, and she specializes in the history of slavery and women in America. She has written a biography of Harriet Tubman and historical books about women living on plantations, and is the former president of the Southern Historical Association.

Fitzhugh Brundage is the department chair of history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He conducted an extensive study of Confederate monuments in the state of North Carolina and spoke about North Carolina as a case study based on research he did well before the events in Charlottesville and Charleston. I wanted to focus on people who had dedicated their careers to these issues. He also talked about the discussion that happened on his own campus to change the name of several buildings.

Deirdre Cooper Owens from Queens College, CUNY, focused on the legacy of James Marion Simms, both his scientific advancements and experiments on enslaved women. He is regarded as one of the foremost scientists in the history of gynecology, and he obtained many of his scientific breakthroughs, the caesarian for example, by experimenting on female slaves, which leads us to consider our standards for acknowledging heroes. What are our general feelings of historical figures that participated in slavery? Are we still going to honor Jefferson or Washington, for example?

Artist Sonya Clark discussed Unraveling, which was conceived in 2015 to mark the 150-year anniversary of the end of the Civil War.

Jason Johnson, a historian based in Texas, looked at how the Holocaust is remembered in Germany, and focused on the Stolpersteine, which are the “stumbling stones” placed in front of individual residencies throughout Europe where people were deported and sent to concentration camps. They are plaques embedded in sidewalks that include the names of those deported, their birthday, the day they were deported, and their death date. Those are somewhat controversial in Germany; not everyone wants a Holocaust memorial on their doorstep. We looked at the debates and discussions around those memorials, and investigated how other countries deal with the problem of having a difficult past.

The artist Nari Ward has been working on a proposal for the Speed and has been a trooper. He has been thinking about this concept for the Speed since before the Confederate monument outside the museum was removed. Initially his project was going to respond to the monument, so he has been rethinking what he wants to do. I love that the project has shifted to acknowledge history.

Jessica Ingram, a photographer, embarked on an extensive oral history and photography project, where she met with families who had experienced the loss of a family member through an act of racial violence, basically retelling their stories. We had four of her photos on view in “Southern Accent.” She talks with these families and acknowledges their desire to have these sites of violence marked. In states that have not elected to mark the site, individuals have taken it upon themselves to make personal memorials. I deliberately included her voice because I think removal and erasure are only one part of the discussion. A vacuum of information can present its own problem.

JO: What were some of your goals for the symposium?

I put this together because I think our feelings toward the South are nuanced. We live in an age where snap judgements are common, and we are encouraged to make snap judgements, and reactions of outrage and anger. There is absolutely a place for outrage and anger, but I am hoping that by providing a forum for discussion, these emotions can be flushed out and talked through and there can be some ground for progress.

I often tell people these things are hard to talk about because the South incorporates both the brightest and the darkest aspects of American history. It was the birthplace some of the greatest genres of American music, blues and jazz, but the South was also home to slavery and legalized segregation. You have the best and the worst combined. It makes it hard to talk about why you love the South without tempering it, and tempting to talk about the frustrating parts of the South without acknowledging all the great things it has to offer.