Slender glyphs in black gouache, ink, and pen on two hundred sheets of paper compose a grid in an airy gallery filled with natural light. The suggested movement and weight of the shapes defy the rigid structure as I look up at the expanse of the wall. In what Torkwase Dyson imagines as processes of “tuning”—a gentle reference for a radical reconceptualization—these “hypershape” forms of Tuning (Hypershape, 311–520) (2018) recall industrial containers for ecological resources, underscoring the precarious infrastructures ingrained in our era of climate disintegration. Rather than halting the chain of signification and ecological unfolding, the drawings generate a visual vocabulary of what Dyson terms Black Compositional Thought. This lexicon of squares, curved lines, and triangles, which are strangely close and also distanced, unlocks the liberatory potential of spatial geometry.

Even with Dyson’s vision of liberation, ICA VCU’s exhibition So it appears runs the risk of disassociating histories from their formal abstracted “truths” of color, light, line, and space. But instead, the artists in the exhibition resist this aesthetic temptation that captivated many of their modernist counterparts of the twentieth-century. What works by Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Monira Al Qadiri, Alexander Apóstol, Navine G. Dossos, Torkwase Dyson, Basmah Felemban, Žilvinas Kempinas, Agnieszka Kurant, Dinh Q. Lê, Jeewi Lee, John Menick, Novo (Reynier Leyva Novo), Trevor Paglen, Walid Raad, Tomás Saraceno, Pak Sheung-Chuen, Levester Williams, Sharon Mashihi, and Tricky Walsh relay under the guidance of Senior Curator and Director of Programs Sarah Rifky and ICA Curatorial Fellow Yomna Osman, is a deft reconsideration of abstraction’s tether to the concrete. The exhibition boldly challenges the meaning of the word abstraction—as a thought or idea without a basis in the physical. Not only does abstraction in this exhibition unveil the ineffable grounds of our reality, but these artists also employ abstraction as what the curators identify as “artistic strategy,” or perhaps artistic strategizing. Abstracting as an action calls for researching and perceiving differently—and this is curious in a cultural moment enamored with the figural and even the melodramatic.

The exhibition is expansive in material, scope, and placement across the institution, ranging from Navine G. Dossos’s gouache paintings on a lower level, to an audio work by Sharon Mashihi accessed via smartphone, and a layered mural of paintings and sculptures by Tricky Walsh activated by augmented reality. Adjacent to Dyson’s drawings are Levester Williams’s To Hold Us All Dear (2015), Agnieszka Kurant and John Menick’s Production Line (2016–2017), Reynier Leyva Novo’s 9 Leyes from the series El Peso de la Historia (9 Laws from the series The Weight of History) (2014), and Basmah Felemban’s The Jirry Tribe Stop (2020–2022). The four corpuses diverge in their handling of abstracted lines and space, but each draws a conclusion concerning bodies in relation to signification.

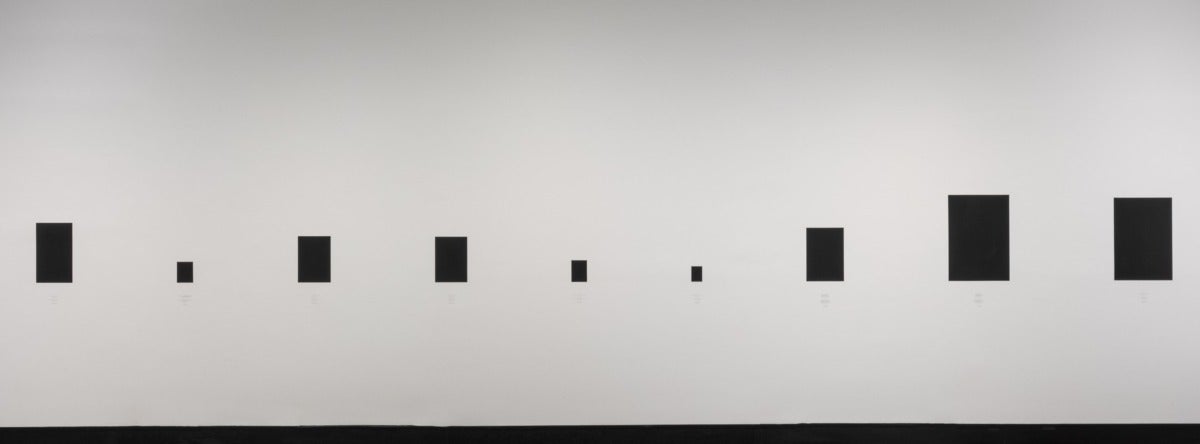

While Williams’s three canvases employ bodily fluids as line-work, Kurant and Menick’s striated mark-making stems from outsourced labor run through AI, Leyva Novo’s fully-redacted documents emphasize an outlining effect, and Felemban’s main character resists the conventions of a line itself. They each conjure more than their formalism initially suggests. Williams’s canvases evoke dreamlike phantasms through accrued sweat on bedsheets from the bodies of incarcerated men in Virginia. The bodily oils are rendered tenderly in their subtle, stained skeins, indexing marginalized bodies apart from their carceral and numeral abstractions. Kurant and Menick’s line drawings lead viewers beyond the individual machinated lines to the “human intelligence tasks” behind the striations carried out by a remote and exploited workforce, or “Turkers.” Rather than reifying the abstracted and inequitable labor in the series, the sale of a Production Line composite drawing benefits each contributor through profit-sharing. Leyva Novo’s El Peso de la Historia takes the familiar redacted line and multiples it—the series turns nine Cuban laws affecting the freedom and movement of citizens into black rectangles, blotted with INk 1.0, a custom technology that approximates and reproduces the exact area and weight of ink in the legal documents on the wall. Felemban’s game delves into space through a gömböc (a virtual shape that only exists theoretically) situated in the Sea of Boards, or a mythical flat plane in the Red Sea. This shape would lead—had the game been operational at the time I was in the galleries—the user on a simulated bodily adventure as the imagined shape itself. In each work, I observed artists aligning individual and collective bodies with points along imaginary lines, leading me deeper into political poetics.

From abstracting the seeming precision and familiarity of a line to defamiliarizing volume, Tomás Saraceno, Jeewi Lee, and Monira Al Qadiri partake in the action. Saraceno’s We do not all breathe the same air (2022) features gray air quality tests from Alaska and Hawai’i serialized into dots, revealing the disparities of our supposedly common air. Lee too abstracts an anthropocentric ecological footprint in ASCHE ZU ASCHE (Ashes to Ashes) (2019). Slate-colored bricks line yet another grid, compacting organic matter, ash, burned wood, and soap. The work memorializes a forest in Italy’s Monte Serra destroyed by an arsonist in 2018. Saraceno and Lee’s sampling of ecological devastation in toned circles and rectangles presents elegiac receptacles for possible reparative cleansing. Al Qadiri’s floating metallic sculptures in OR–BIT (2016–2018) at first elude a terrestrial connection, until their oil-like sheen gives themselves away. Oil rig parts hover above their plinths, wielding the power and ubiquity of the unseen substance that drives twenty-first century life.

Throughout the exhibition, color appears prominently but not in the ways I had expected. Based on modernist precedents from the mid-century, such as proponents of color field painting, I half-imagined that abstracted color might direct viewers to a neat symbolic legibility. Bright monochromatic paintings by Alexander Apóstol, mauve and sage-colored camouflaged wallpaper by Pak Sheung-Chuen, chromatic pixelations in Dinh Q. Lê’s four channel video, blues in The Atlas Group/Walid Raad’s Secrets in the Open Sea, 1994/2004 (2004), and Trevor Paglen’s acrid color studies distance us from political parties, protests, trauma, buried histories, and centers of incarceration in order to draw viewers close to a keen, affective uncertainty in governing systems, collective beliefs, and memorial residues.

The hue that lingered in my mind was cerulean. Sky views lined the walls in Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s Air Conditioning (2022), animated by Žilvinas Kempinas’s kinetic sculpture, Double O (2008). Abu Hamdan catalogs Israeli “atmospheric violence” in Lebanese airspace from 2007–2021 through collated data across nine panels of cloud formations. The immersive effect of the Abu Hamdan panels with Kempinas’s double fans blowing contorted video tape through the air constitutes a visceral clashing of movement and color. In that space I felt the disappearance of humanity within the abstracted blue to a zero degree. That excerpt of blue felt much like the shape of Trevor Paglen’s Trinity Cube (2017) with trinitite residue from U.S. nuclear tests in New Mexico prior to the atomic attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and irradiated glass from the Fukushima nuclear disaster: a bald proclamation. And it dawned on me that the warring movement underlying color, volume, and line cannot be separated from these formal properties. These artists strategically build an abstracted tension between closeness and distance that gestures toward the seeming impenetrability of contemporary violences.[1] And yet, by holding fast to that seeming impenetrability, reshaping and recontouring it, resistance seeps into the stroke of a line, the design of volume, and the stain of color.

[1] I am grateful to Bryn Evans for providing insightful editorial guidance and offering prescient thoughts concerning impenetrable or unspeakable violences.

So it appears is on view at the Institute for Contemporary Art at VCU in Richmond through July 16, 2023.