Washington “Doc” Harris had a clear vision for his life’s work— “This place is a sign for future generations and the fallen of the world.” He was referring to The Saint Paul Spiritual Holy Temple, a complex of sacred structures created by the Harris family beginning in 1957 where Doc Harris led a Christian congregation and performed spiritual healing. Once intended to welcome all who sought his help, Harris was instead forced to close the Temple to outsiders after becoming a target of violent and often racially motivated harassment. Today, the Harris family hopes to finally fulfill Doc’s vision to open to the Temple to the public as a site of healing and reconciliation.

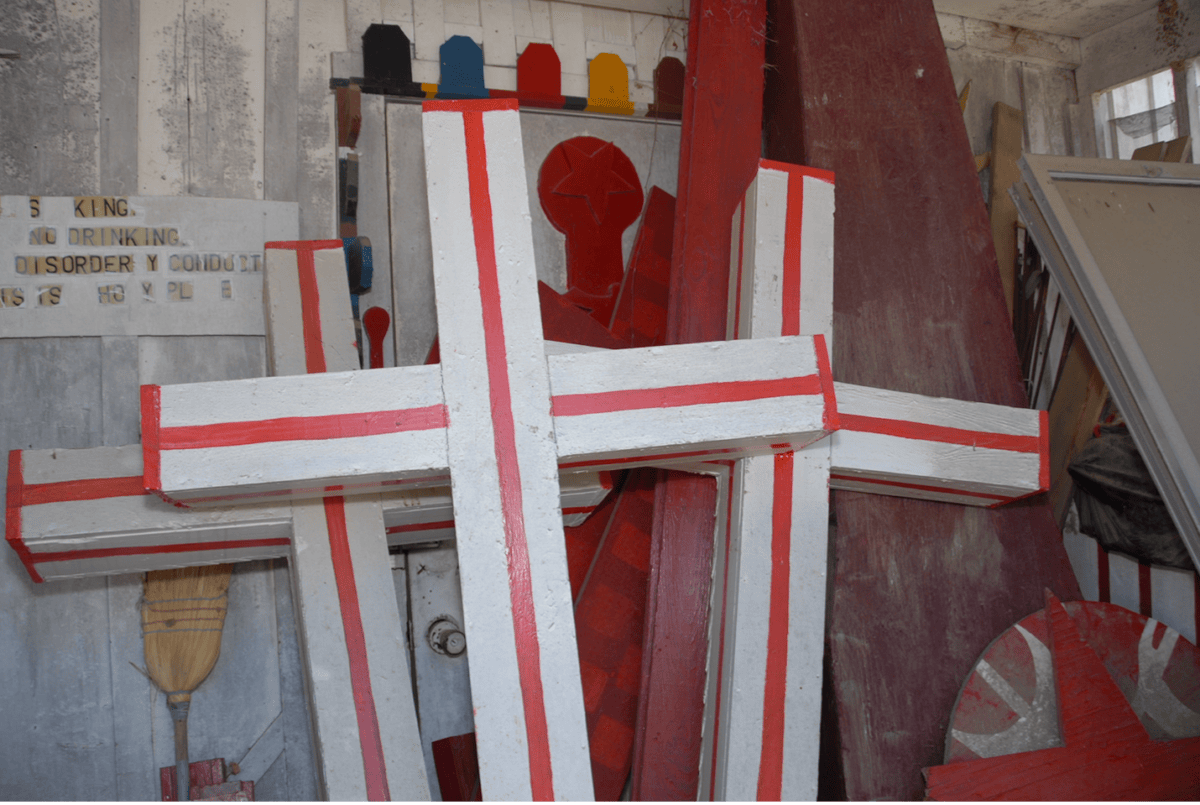

In 1947, Doc Harris moved his family from northwest Mississippi to a rural area then on the outskirts of Memphis, Tennessee, called Boxtown, a community originally settled by formerly enslaved people soon after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. To facilitate Harris’s church and healing practice, the family built an extensive compound of buildings and residences including a large rectangular chapel where services were held. As a crucial extension of the spiritual work taking place on site, Harris—using Biblical and Masonic principals as the primary references—directed the family to also construct an ever-growing collection of intricately crafted and highly symbolic sculptures. These sculptures, titled The Degrees of God and Craftwork and referred to as simply “Craftwork” by the family, take the form of wood assemblages installed in the yards and passageways of the property, mannequin-populated tableaus illustrating Biblical tales and parables, miniature structures formed from tightly-woven cane harvested from a canebrake in the Mississippi Delta, rams and other creatures affixed with brightly colored and elaborately patterned beads and costume jewelry, silken tapestries draping the chapel interior, and other magnificent, handcrafted sculptures whose meaning would only be clear to those initiated into the secret fraternal organizations of which Doc Harris was a proud and active member.

The process of creation was this—Doc Harris would receive a divine message from God regarding the arrangement of materials to create a new object to join the collection of Craftwork. He would then dictate the specifications of the object to his grandson Washington James “Mook” Harris, the current leader of the Temple, who would sketch as Doc spoke. The description of the piece was often more sophisticated than Mook believed he had the skills to develop. “A lot of times he’d tell me, ‘You think you can make that for me?’ And I’d say, ‘Nope, I can’t make that. [Doc would respond] ‘Oh yes you can, go ahead on,” Mook recalled with a laugh during my visit to the Temple in July 2021. The approved sketch would be constructed by Mook and other male family members, and the surface would be painted or decorated by two of Mook’s sisters (Caroline and Bert Harris) and other female members of their extended family. Colors and pattern variations were subject to final approval by Doc. The manifestation of this enormous body of work was truly a family affair. According to the family, if Doc had lived to continue receiving divine inspiration, the site would have stretched more than 30 miles south to Tunica County, Mississippi.

After several years of focused creation, Doc Harris contacted the Memphis Press-Scimitar, a local newspaper, with an invitation to the property. The newspaper sent a reporter to interview the doctor about his work at the Temple, resulting in the 1961 article, “The Doll’s Aren’t ‘Voodoo’ He Said — He Calls Them Symbols of God.” The unfamiliar forms in the yard, the seclusion of the property, and probably most significantly—the Black Indian[2] imagery and identity of the family—had resulted in swirling rumors of bloody rituals, sacrifice, and violence against those that might dare trespass on the property. Locals deemed the site “Voodoo Village”—a pejorative label that unfortunately continues to be the most widely used moniker for the Temple. Addressing this gross misunderstanding, Doc Harris is quoted in the article, “We have an eternal organization here. A church. Our temple is the most beautiful place in the world. All these things have a meaning. They are symbols of God.” In a column directly adjacent to this piece appears another article regarding a reporter from the same paper trespassing at the Temple and subsequently being arrested. While the first piece refers to the site as the “Temple,” the second uses “Voodoo Village” and lists the street address. Doc Harris’s intention to share the truth of the Temple—a holy place of worship and healing—instead resulted in sixty years of ongoing provocation from trespassers. Over the years, Mook Harris has reported varying degrees of harassment recurring at least once a week from dumping garbage in front of the gates, to killing one of their guard dogs, to actively shooting into the property where he and his wife Ella live. “I ain’t had a good night’s sleep in my own home since me and my old man built this place,” he says. Doc Harris was eventually forced to close the Temple to all but his clients and members of the church in the early 1960s, and due to continued safety concerns, it remains closed today.

Despite these many decades of willful ignorance and abuse, the Harris family is now dedicated to opening the Temple to the very community that has actively caused them harm. Mook Harris is hopeful that providing access to the healing space and the spiritual and creative work being done there will illuminate the true meaning of the place. “This is no voodoo. All of this is parts of the Bible or the Masonic Order,” says Harris. While Doc Harris delivered that same message via the local newspaper decades ago, his grandson believes the community has the capacity to finally recognize and celebrate the true significance of the Temple and generously hopes to facilitate that shift in future generations, saying, “It’s bad to be old and still a fool, but it’s worse to be young and a fool and never change.”

The Temple presents a meaningful collision of the material culture of the South, the hybridization and fluidity of spiritualities, both forced and voluntary cultural fusions, and the legacy of white supremacy; the story of the place, the artwork, and the Harris family is long and complex and just beginning to unfold. Artist, Professor Emerita of Drawing and Painting at the University of Georgia, and longtime friend of the Harris family Judith McWillie is currently editing and contributing to a book about the Temple. According to McWillie, the Temple opens the door to new research on the demographics of Memphis and North Mississippi, and a clearer understanding of Africans and Indigenous people moving west from the Atlantic Coast of North America following the earliest days of the transatlantic slave trade. While Harris’s healing practice was a divine gift unique to him (no other members of the Harris family have been gifted with healing since), the church he developed and led in southwest Memphis aligns both philosophically and materially with a network of Spiritual Temples throughout the South, with a former concentration of locations in New Orleans. These Spiritual Temples fused Christianity, Native spirituality, and African diasporic traditions. The Craftwork make these traditions tangible and provide a crucial lens into the dynamic merges and shifts of identity in the American South as well as the whole of the United States. “People need an ever-expanding American story, and the Temple is deeply American. When people relax and understand that history is not their enemy, that all great histories tell of the strife that precedes spiritual growth, they will see that, while we human beings are all problematical to some extent, there have always also been creators who transcend the chaos and point a way toward inspiration and a vision of something better,” says McWillie.

The preservation and interpretation of artist-built environments—personal spaces like homes, gardens, and studios fully transformed into continually evolving, site specific, and life encompassing works of art—is the current focus of several arts organizations in the South. The Atlanta-based Souls Grown Deep Foundation is partnering with The University of Alabama to digitally map Joe Minter’s “African Village in America” in Birmingham, Alabama, and this documentation will be made available to the public. This is, hopefully, just the first step in protecting the sprawling site filled with installations addressing Black history. Minter is quoted in a September New York Times article, “I can hear the bulldozer coming… I’ve been waiting on someone to preserve this.” A similar documentation project regarding Dr. Charles Smith’s African American Heritage Museum and Black Veterans Archive in Hammond, Louisiana, was recently led by Tulane graduate student Emma Mooney and will be of great importance to potential future conservators considering the site’s increasing vulnerability to weather damage driven by climate change. Souls Grown Deep also provided funding in 2019 for the preservation of Margaret’s Grocery, a site in Vicksburg, Mississippi, that is unfortunately quite dilapidated and in desperate need of conservation. Artist Nellie Mae Rowe, creator of an environment she called her “Playhouse,” is featured in a major exhibition on view now at The High Museum in Atlanta. Though the site is no longer extant, the exhibition includes photos of the Playhouse alongside discrete works, affirming the significance of the home-as-assemblage as the setting of Rowe’s creative practice.

The Harris family has also provided the public some off-site visibility of the Temple through institutional partnerships. Recently retired curator of the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art Marina Pacini featured five pieces from the Temple in the 2012 exhibition The Soul of a City. Due to the spiritual nature of the Craftwork, they were not presented with other objects and were instead displayed in a private, reverent space, as requested by the family. The Craftwork and other work presented in the show provided an important touchstone to visual art produced in the Midsouth as the cultural identity of Memphis and the surrounding area is primarily associated with music. Regarding the potential of preserving and opening the site, Pacini says, “The Temple offers an extraordinary opportunity to pull together many threads, not just of Memphis, or of the region, but of the country’s history. The story of Doc’s family, the development of the Temple, and the role it played in its community is one that needs to be preserved.” Two Temple objects, “The Red House” and “The Crosscut Saw,” were also presented in the critically acclaimed 2015 exhibition When the Curtain Never Comes Down: Performance Art and the Alter Egocurated by Valérie Rousseau at the American Folk Art Museum in New York. In her review of the show, New York Times art critic Roberta Smith highlights the pieces from the Temple and says of the exhibition, “it may be best to approach this show knowing that each endeavor revealed here, each life touched on, is something of a world unto itself — if not a complete cosmology.”

Perhaps the greatest legacy of the Temple is the space provided for healing. According to McWillie, who first met Doc Harris when she sought out his services as a spiritual doctor in the 1980s, a selection of Craftwork was mounted in a room adjacent to Harris’s office. He would take clients into this room to reveal a “vision of paradise” here on earth. The crux of Harris’s teaching was not a focus on a heavenly reward, but rather the reassurance that “this is what God created you to be.” Through the shocking beauty of the work, the intricacy of its craftsmanship, and the density of the display, Doc Harris and his family generously created a more accessible vision of heaven for those in need on Earth. Though the future of The Saint Paul Spiritual Temple is unclear, one thing is certain— the Harris family must have respect and privacy as they determine their next steps toward reopening the site. For those who wish to see examples of Craftwork, two pieces are on display at the Jay Etkin Gallery (942 S. Cooper St., Memphis). For the time being, the site remains closed to the public.

[1] Walker met Doc Harris while working on a book about Reverend Louis Cole, a circuit preacher who served Black Baptist congregations in west Tennessee and north Mississippi. One day Reverend Cole requested that Walker take him to the doctor. Rather than arriving at a family medicine office, Walker was surprised to find himself at The Saint Paul Spiritual Holy Temple. It was sacred medicine that Rev. Cole sought. Walker went on to visit Doc Harris many times, becoming “like a son,” according to his widow Mary Mhoon Walker. Walker was the only person allowed to photograph the site during its prime and fought tirelessly for its preservation until his untimely death in 2014.

[2] The Harris family is of African and Indigenous ancestry, and they identify as Black Indians.

This essay is part of Burnaway’s yearlong series Artist Environments.

Find out more about the three themes guiding the magazine’s publishing activities for the remainder of 2022 here.