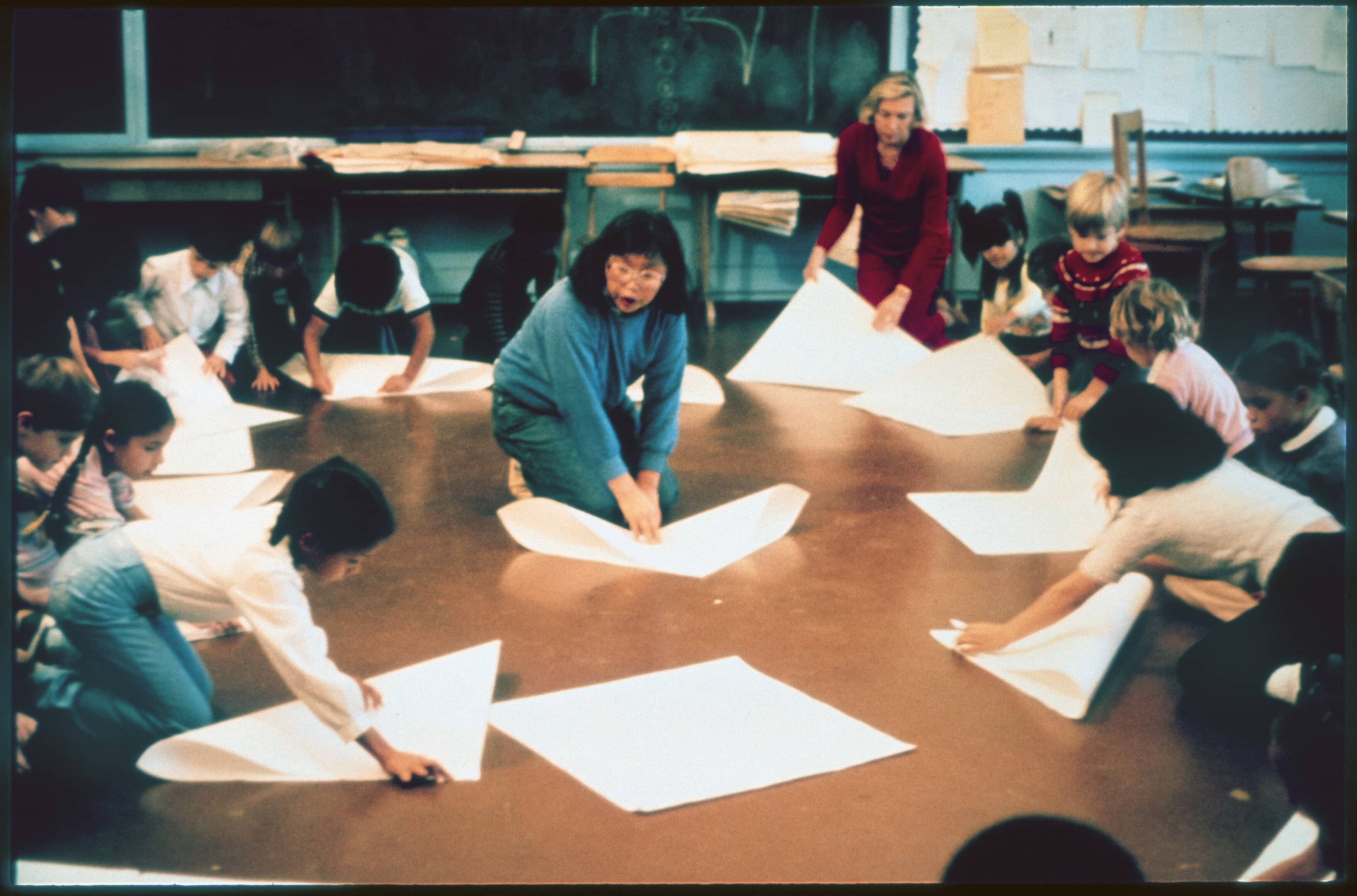

Photo by Mary Parks Washington and image courtesy of Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc.

“An artist is not special. An artist is an ordinary person who can take ordinary things and make them special.” Ruth Asawa

Ruth Asawa, aspiring to become an art teacher, attended the Milwaukee State Teachers College from 1943-1946, but the school refused to assign her a student teaching role she needed to graduate, citing lingering anti-Japanese attitudes. As a result, she was forced to drop out. This rejection would send Asawa down an unlikely path of creative exploration that influenced her artistic and academic career.

The origin of this path began at Black Mountain College, a liberal arts school deep in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina. The institution radically challenged the intellectual and philosophical underpinnings of school governance and teaching practices, prioritizing independence and democratic principles that privileged the process of learning over the formalities of rank and academic designation. Under the tutelage of Josef Albers, Asawa refined her approach to material, process, and pedagogy, famously noting that Albers didn’t teach students how to draw, “he was teaching you how to see.”1 By examining the contours of line through a disciplined practice of repetition, she mastered the art of meandering with a plan, a process she extended into her personal journey as she encountered detours in her life. Black Mountain catalyzed Asawa’s artistic career—traces of their influence recur in her biomorphic, looped wire sculptures, origami fountains, and public monuments. Asawa eventually found her way back to teaching art, invoking Black Mountain principles within public schools in San Francisco, California. Asawa didn’t follow a map or a prescribed path to chart her career, instead she navigated life using Black Mountain as her compass.

Black Mountain College, founded by John Andrew Rice and Theodore Dreier in the 1930s, was located near Asheville on 640 acres of verdant farmland in the Blue Ridge Mountains. At its peak the multi-disciplinary, multi-cultural community of exiles, artists, and performers created a perfect storm of artistic expression in the 1930s-1950s, attracting art and design juggernauts including Buckminster Fuller, Jacob Lawrence, Merce Cunningham, and John Cage. While at Black Mountain, Asawa drew from her rich life experiences, creating a series of successive works that personified her adaptability, resourcefulness, and discipline.

Ruth Asawa was born in Norwalk, California in 1926 and raised in a family of Japanese truck farmers in a rural, unincorporated community east of Los Angeles. As a child working on the farm, Asawa traced interlocking hourglass shapes into dusty dirt tracks with her foot as she rode on the back of a horse-drawn land leveler.2 She indulged her artistic proclivities by becoming an avid illustrator with dreams of attending the Chouinard Art Institute, however, amid a climate of anti-immigrant land ownership laws, intensifying anti-Japanese sentiments, and economic disenfranchisement, her educational prospects were completely derailed during the Great Depression and World War II.

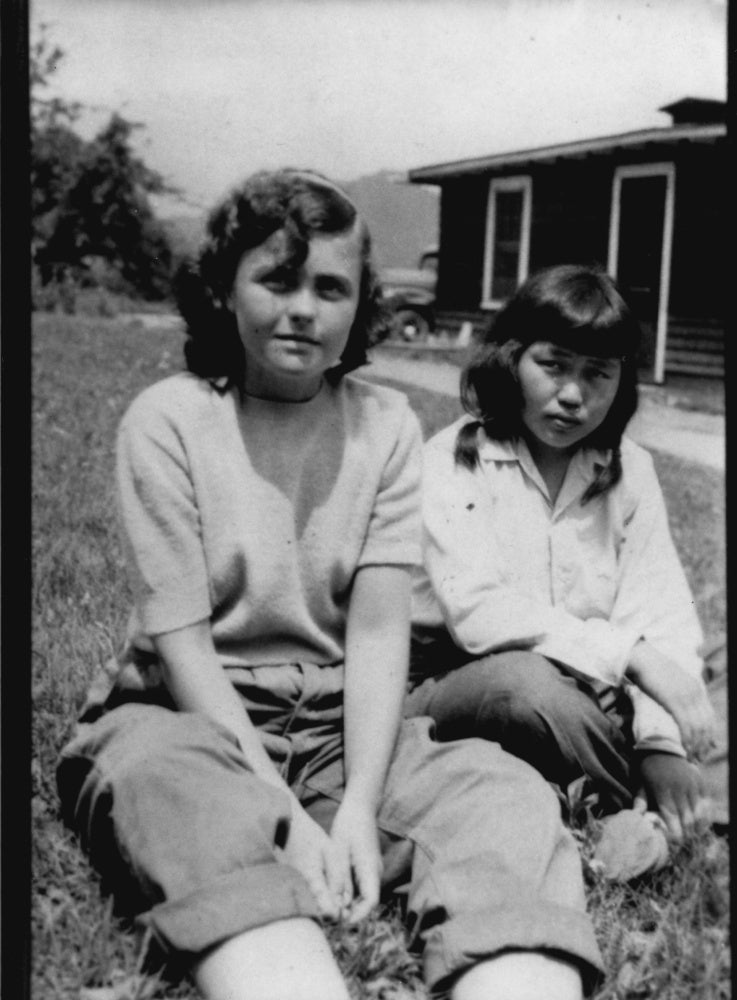

In the wake of Pearl Harbor in 1942, FBI agents arrested Asawa’s father under the unjust Executive Order 9066 and imprisoned him in New Mexico while Asawa, her mother, and 5 of her siblings were forced into incarceration in converted horse stalls at the Santa Anita racetrack. At Santa Anita, internees maintained schooling for detained children; Asawa took art and illustration classes with incarcerated Walt Disney animators including Chris Ishii, landscape artist Tom Okamoto, and cartoonist Ben Tanaka.3 Asawa was later transferred to the Rohwer War Relocation Center just outside of McGehee, Arkansas, where she continued to draw and paint, using the skills she honed in California to become the art editor of her high school yearbook. After graduating she was released from Rohwer to attend Milwaukee State Teachers College, and while there befriended a fellow student named Elaine Schmitt whose older sister Elizabeth attended Black Mountain College. In letters she sent to Elaine, Elizabeth beckoned her sister and friends to attend the progressive, liberal arts school.4

Josef and Anni Albers joined the teaching staff at Black Mountain as émigrés from Germany during World War II, eventually encouraging fellow Bauhaus stalwarts fleeing persecution to teach at the school. While most students studied at Black Mountain for a semester or single summer session, Asawa spent three years there, learning through a curriculum rooted in repetition, revision, and refinement, core principles that Josef and Anni Albers adapted from Bauhaus traditions that espoused intuition, collaboration, and experimentation. During the 1946 summer session Asawa took core classes in design and color with Josef Albers. A favorite drawing exercise of his was the Greek meander, a single repeated interlocking line that resembles a key motif, repeating the meander through varying articulations of scale, shape, and shading. In class students presented their work to one another, detailing how they approached a particular assignment; through these critiques, Albers taught students to focus on process over product, instilling discipline in gathering information that they later applied in successive classes. Instead of completing a course and graduating to a higher level of study, Albers encouraged his students to maintain fidelity to the original material by manipulating and interacting with it in new ways.

The school was notoriously cash and resource strapped—students relied on everyday materials to create their work so frugality, upcycling, and resourcefulness were beneficial skills. While arduous work-study requirements, including manual labor, dissuaded many students, Asawa embraced these challenges as opportunities for learning. Asawa was uniquely prepared for her Black Mountain experience. “We used everything that was natural around us… I grew up on a farm, and I knew that we always improvised on the farm. So, I felt very much at home because it came out of necessity rather than having everything in front of us.”5 Through this approach to problem solving Asawa continued to apply this process of adaptation in her life, using what was around her to create something new.

Asawa’s notes and drawings during her three years of study reveal familiar patterns in color, material, and shape. She frequently drew variations of the meander motif, playing with perception, line, volume, and transparency using ink, collage, and other techniques to experiment with the pattern. Examining her adaptations of the meander, the seeds of her most iconic biomorphic forms take shape; in other modes of experimentation she would translate her two dimensional drawings into three dimensional sculptures through origami; she would then reverse the process by deconstructing her work and drawing new two dimensional shapes.6 Echoes of the meander would reappear many years later in the carved doors found at the entrance of her Noe Valley home in San Francisco.

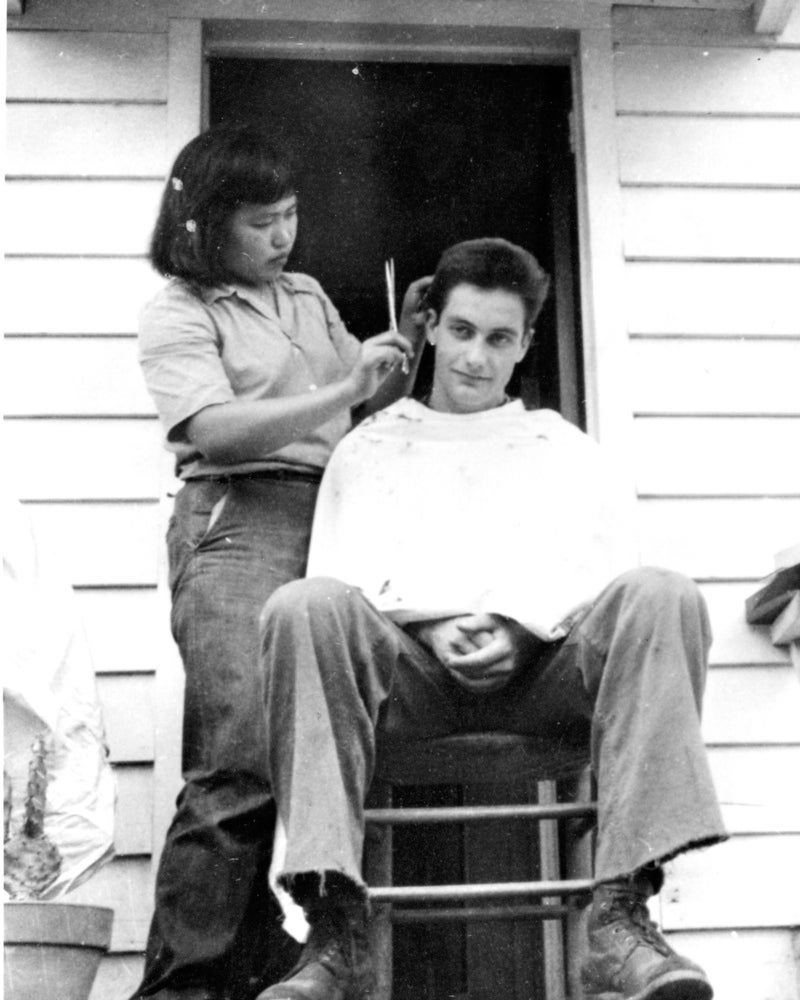

Asawa’s travels to Mexico, particularly her trip to Toluca in 1947, offered fertile creative ground for translating the concepts she honed at Black Mountain into three dimensional, sculptural renderings. While she taught school children in Toluca, Asawa also learned how to make looped-wire egg baskets which would become the foundation for her looped-wire sculptures. When she returned to Black Mountain she toggled between two dimensional representations of a continuous, looped line and the transparent “form within form” structures she created with wire, remixing this concept for decades. This sustained practice of experimentation marks the genesis of the rules and concepts that defined her metier.

Asawa met her husband, architect Albert Lanier at Black Mountain and the two relocated to the Bay Area to raise six children. She continued to make her wire sculptures while experimenting with new, unconventional materials like salt dough, also known as baker’s clay made from a simple recipe of flour, water, and salt. A familiar occurrence, necessity became the mother of invention. “If I didn’t have my own children I would have never explored working in dough…because I had six children at home I had to find things to do with them, and it began with making Christmas ornaments. They are very much the inspiration for working in dough.”7

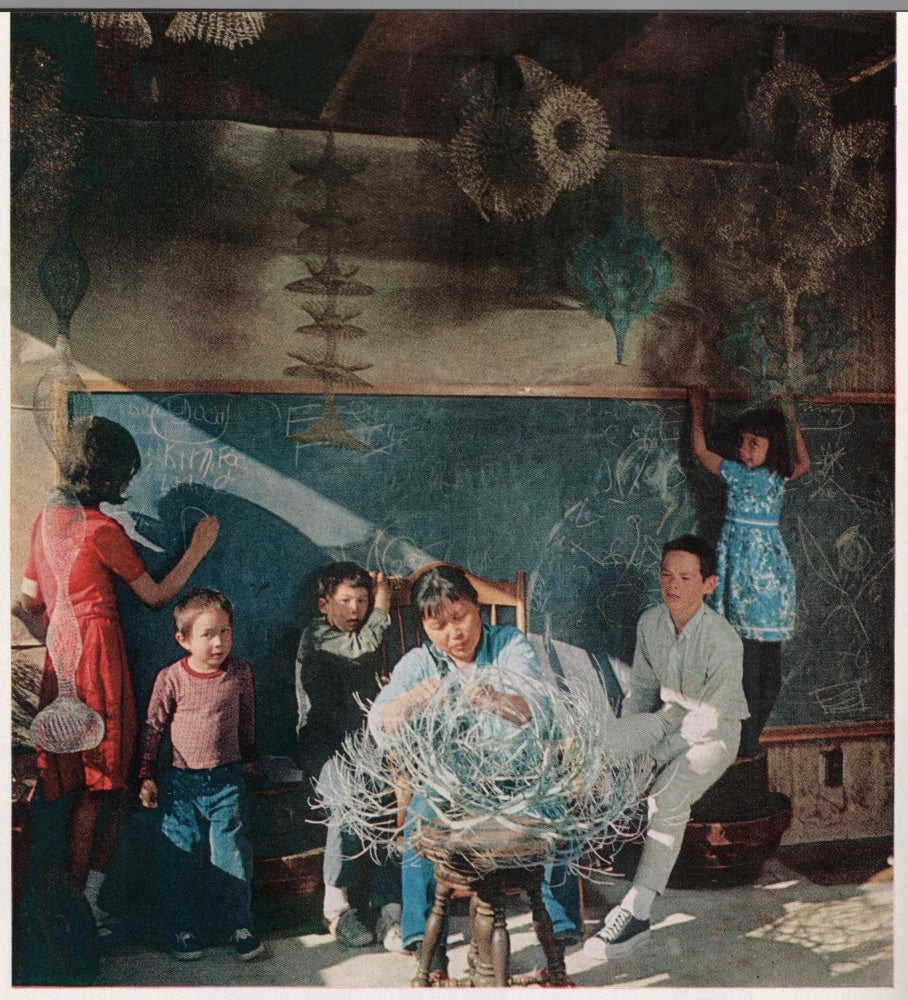

This period of material experimentation eventually led Asawa back to education, when in 1968 she and a fellow parent founded the Alvarado School Arts Workshop, a program that brought professional working artists, gardeners, and parents into schools. Through art classes Asawa taught children how to fold origami and sculpt baker’s clay figures using simple materials to reinforce the idea of doing more with less, while encouraging students to observe and experiment.“I would like the children to have an area where they can make decisions about design, materials, and what they do; that’s really the first step in problem solving.”8 This became the foundation of her teaching ethos, once again invoking Black Mountain. Asawa’s experience at Black Mountain grounded her creative practice and guided her unconventional path to education by teaching her how to listen to the materials she had on hand and refine her ideas through experiments with line, folds, and manipulation. “The material is irrelevant,” Asawa once said. “You take an ordinary material like wire and you give it a new definition. I’m interested in what it can do by itself and that’s what excites me…It’s the distance between effort and effect.”9 Traversing that line both in life and her art, Asawa gave shape to new ideas and innovative forms, methodically meandering in mesmerizing ways.

Asawa’s experience at Black Mountain grounded her creative practice and guided her unconventional path to education by teaching her how to listen to the materials she had on hand and refine her ideas through experiments with line, folds, and manipulation.

[1] Asawa, Ruth. Interview by Mary Emma Harris. 17, February 1998. https://as.library.appstate.edu/AC%20564/189%20RUTH%20ASAWA%20TRANSCRIPT%20R EVISED.pdf. Accessed 14 May 2025.

[2] Wakida, Patricia. “Bronze, Sky, and Stone: Ruth Asawa’s Art in the Public Realm”, Reflecting on Ruth Asawa and the Garden of Remembrance, Fine Arts Gallery, San Francisco State University, 2024. https://gallery.sfsu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/Reflecting%20on%20Ruth%20Asawa%20and%20the %20Garden%20of%20Remembrance.pdf. Accessed 14 May 2025.

[3] Wakida,“Bronze, Sky, and Stone: Ruth Asawa’s Art in the Public Realm”.

[5] Von Uchtrup, Michael. “Ray Johnson and the Road from BMC Into—and Out of—New York,” Journal of Black Mountain College Studies Volume 2, Spring 2012. https://www.blackmountaincollege.org/volume2/ray-johnson-biography/. Accessed 14 May 2025.

[6] Conaty, Kim, and Clara Rojas-Sebesta. “Asawa on Paper.” YouTube, Whitney Museum of Art, 27 Nov. 2023, www.youtube.com/watch?v=3uLhtgwe0rU&t=1378s. Accessed 14 May 2025.

[7] San Francisco’s Ruth Asawa (1979). You Tube, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. 2 May 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SipUt3GKXsU.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Johnson, Mark, and Paul Karlstrom. “Oral History Interview with Ruth Asawa and Albert Lanier, 2002 June 21-July 5 | Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution | Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.”, www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-ruth-asawa-and-albert-lan ier-12222. Accessed 31 May 2025.