On a rainy Monday in May, I decided to venture out to the Georgia Guidestones in Elbert County, a mysterious arrangement of monoliths near the South Carolina state line. Churning over the Atlantic, tropical storm Alberto was threatening to turn into a hurricane, sending persistent rain and sporadic thunderstorms. The turbulent weather caused my phone’s GPS to repeatedly lose signal, the blue dot that represented my location was veering wildly into the flat green wilderness around me. I’ll get there, I thought. Maybe I wanted to get lost—to give into wanderlust or test the mystical pull of the Guidestones. I eventually found my way, though I failed to feel the energy some people believe the monumental stones possess. And the stones would lead the way to an even older monument, one tied to the history of the town of Elberton’s granite monument industry.

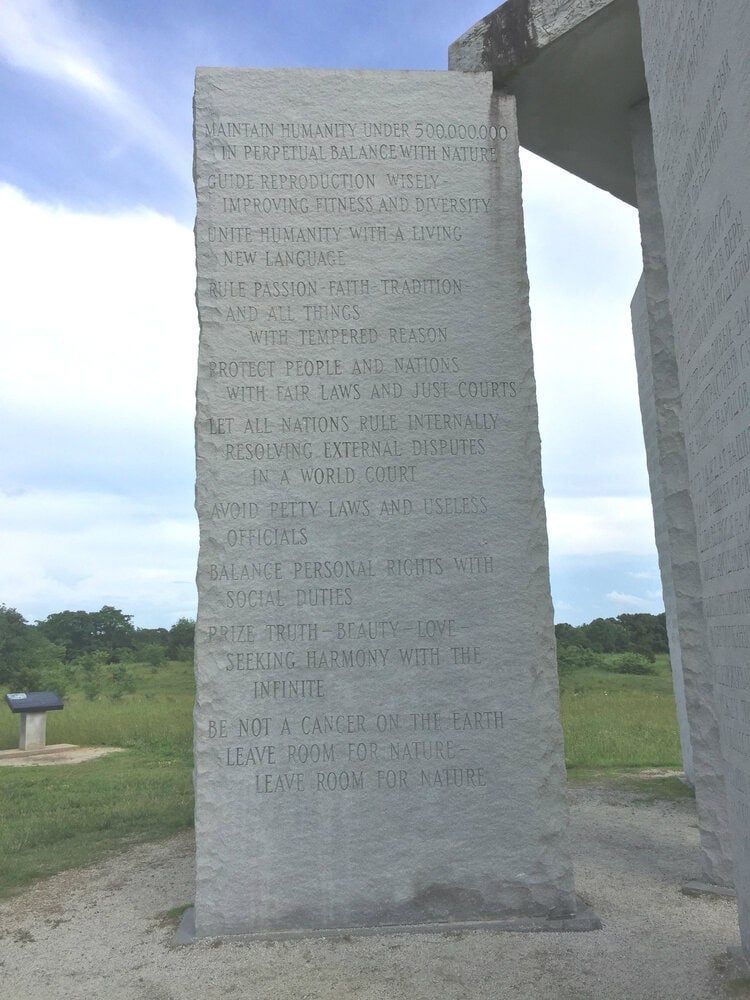

Unveiled on March 22, 1980, the Guidestones consist of six giant slabs of gray-blue granite sourced from the nearby Pyramid Quarry. Four megaliths surround a central stone like wheel spokes, each inscribed on front and back with 10 rules to guide humanity—like the Ten Commandments for a modern audience. The identity of the person or group responsible for their creation remains a guarded secret.

An anonymous man known under the pseudonym Mr. Christian, and later as R.C. or Robert Christian, approached Joe Fendley, president of the Elberton Granite Finishing Corporation, with plans for the project in June 1979. Why Elberton? Christopher Kubas, Executive Vice President of the Elberton Granite Association, told me that original plans indicated that the Guidestones would be built somewhere in the southern part of Georgia, where flatter ground would provide better views from afar. But lack of funding or the logistics of moving the massive stones over bridges and roads not designed to accommodate their weight kept the stones in Elberton. According to accounts from the former president of Granite City Bank, Wyatt C. Martin, Christian cited the remote location, the natural wealth of granite, the warm weather, and a maternal link to Georgia as reasons for the selection. Due to the requirements of the financial arrangements made between Christian and Martin, the banker knows Christian’s real identity, but he’s sworn to confidentiality. Once the funding and project management were secured, production began. It took a little over a year to complete the monumental Guidestones.

There are many speculations about the chosen location and intentions of R.C. Christian. Literature on the Guidestones is of varied credibility, from photocopied pamphlets and newspaper articles to conspiracy theory–minded blogs and YouTube videos. In 2011, a book was published by The Disinformation Company.

Often cited is the numerical significance of the number seven. To be sure, the number comes up a lot if you’re looking for it: the monument is located off Highway 77, next to Double 7 Farm, 7.2 miles away from Elberton, and 7.8 miles from Hartwell. Also, the Guidestones are about 10 miles away from Ah-Yeh-Li A-Lo-Hee, the center of the world according to the Cherokee, who used the site for tribal councils and as an assembly ground. A stone marker now memorializes it. Elbert County’s underground granite might also provide stability in the case of an an earthquake or other natural disaster, as was pointed out in a 2015 BBC article.

A 2012 low budget documentary works hard to dispel the rumor that the Elberton Granite Association (EGA) created the Guidestones as a tourist attraction. It gives insight into the process of making the stones and some of the theories it has engendered, exploring links to the Freemasons as well as the popular notion that R.C. Christian’s assumed name alludes to the Rosicrucian Order. Allegedly founded in the 14th century by a man named Christian Rosenkreuz, the secretive Rosicrucians combine elements of Christianity, Judaism, and the occult that purportedly originated in the ancient world. (Incidentally, like the Guidestones, the reputation of French artist Yves Klein, an avowed Rosicrucian, wavers between mysticism and charlatanism.)

My journey to the Guidestones felt rambling. It took me past a gutted house poised to be moved on skeletal, stilt-like supports above rust-colored dirt dug out like a fresh wound; past a Winnebago for sale and a large sign advertising “BUBBA’S: OPEN 24 HOURS”; past many iterations of the American flag, some painted boldy on garage doors, and the occasional Confederate emblem (the co-mingling ever paradoxical, as the express purpose of the latter is its anti-Americanness); past countless side roads with romantically apt monikers like “Far-A-Way” or “Wipporwill”; past ruined hunting stands in a field of tiny young pines; and, once by mistake, past the South Carolina border, where the roads became craggy and unkempt.

I knew I was getting close to the Guidestones when I saw piles of granite slabs and sample gravestones ominously left blank. A downtown sign proclaimed Elberton to be the “Granite Capital of the World.” With over 45 quarries, the city produces more than 250,000 granite monuments annually, according to the EGA. Indeed, granite gave Elberton a needed financial boost in the Reconstruction era and remains vital to its citizens, providing many jobs. Perhaps morbidly savvy to the economics of this industry, a church sign announced in all caps, “THE WAY TO LIFE IS DEATH.”

Eventually, my phone announced in its flat, authoritative voice that I should turn onto a dirt road. Immediately visible, the Guidestones towered over a grassy field, dramatic under the murky sky. Strategically placed at the zenith of Elbert County’s highest hill, they are located on five acres of land bought by R.C. Christian and later deeded to Elbert County. I parked on a gravel plot and walked through an opening in a chain link fence, heeding the tall nearby camera surveilling the site.

From ground to capstone, the Guidestones measure just over 19 feet tall, and rest on 4 feet of underground reinforced concrete. Once standing under the impressive six-stone structure, it’s hard not to imagine ancient prototypes like England’s Stonehenge. Certainly, they mimic the astronomical configuration of that Neolithic site—that is, the idea of orienting the monument to the celestial phenomena, not the actual arrangement. A tall, vertical Gnomen stone marks the center, its name referring to the upright central point in a sundial. It is the hub, and with the four megaliths supports a rectangular capstone. It is the heaviest single stone on site, weighing almost 25,000 pounds. An opening in the Gnomen stone aligns with the North Star and, supposedly it is visible through a long, narrow a small opening. A hole in the capstone lines up with the midday sun, its light designed to indicate the day of year on the surface Gnomen stone below, though according to Kubas, the bronze plaque that would indicate the specific date was never installed. A rectangular opening in the Gnomen frames the rising sun on the horizon on solstices and equinox days. Incidentally, it also provides a view of an informational placard on a pedestal located to the east of the Guidestones.

The Guidestones’ decrees appear in eight languages, each stone carved on both sides. Walking around the monument, visitors can see the Gnomen stone and two flanking megaliths from the four cardinal directions: English and Russian face north, Chinese and Arabic face west, Hebrew and Hindi face south, and Swahili and Spanish face east. The four-sided capstone features ancient texts: Babylonian cuneiform points north, Egyptian hieroglyphics point west, Sanskrit points south, and ancient Greek points east. Given the meager number of specialists who might be able to read the dead languages, these lack practical function, a bald manifestation of the Guidestones’ false archaism.

The Guidestones are a little like the artificial ruins created by European elites during the Romantic era. But imbued with their makers’ odd and questionable mission, they aren’t merely nostalgic aesthetic ornaments. On the west side, a flat ground marker gives basic information about the stones, including physical data and an attribution to R.C. Christian, listed even here as a pseudonym. At the bottom of the bottom, are instructions to visit the Elberton Granite Museum and Exhibit for more information. I snapped a picture, making a note to visit. A mantra of sorts appears in the center of the plaque: “LET THESE BE GUIDESTONES TO AN AGE OF REASON.” Despite its optimism, this maxim is also chilling. If the Enlightenment’s legacy teaches anything, it’s this: sometimes one man’s progress is another’s persecution. Not only do the Guidestones conjure up ancient henges, they evoke sci-fi harbingers of doom, like the enigmatic monolith of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey

The 10 precepts of the Guidestones range from basically agreeable to morally suspect. The first decree belongs to the latter: “MAINTAIN HUMANITY UNDER 500,000,000 IN PERPETUAL BALANCE WITH NATURE.” With the global population now approaching eight billion, this mandate is laughably outdated and sinister—achievable only through, say, genocide or a worldwide disaster. (It also sounds a bit like the scheme of the villainous alien god Thanos in this year’s Avengers: Infinity Wars, and the tightly controlled dystopia it portends evokes Logan’s Run, made just four years before the Guidestones were unveiled.) Equally alarming, the second principle smacks of eugenics, commanding that we “GUIDE REPRODUCTION WISELY—IMPROVING FITNESS AND DIVERSITY.” The third advises that we “UNITE HUMANITY WITH A LIVING NEW LANGUAGE” optimistically evoking a ’60s hippie ideology.

After the first three, the guidelines become generic and inoffensive: “RULE PASSION—FAITH—TRADITION AND ALL THINGS WITH TEMPERED REASON.” Notwithstanding a disdain of heavy and incorrect em-dash usage, it seems like good advice. They continue in relentless four-inch all-caps: “PROTECT PEOPLE AND NATIONS WITH FAIR LAWS AND JUST COURTS; LET ALL NATIONS RULE INTERNALLY, RESOLVING EXTERNAL DISPUTES IN A WORLD COURT; AVOID PETTY LAWS AND USELESS OFFICIALS; BALANCE PERSONAL RIGHTS WITH SOCIAL DUTIES.” The final rule repeats itself with poetic bravado and more em-dashes, but the message is timely. I felt some remorse to read, “BE NOT A CANCER ON THE EARTH—LEAVE ROOM FOR NATURE—LEAVE ROOM FOR NATURE.”

The Guidestones incur clerical criticism and occasional vandalism, such as a 2009 defacement in red spray paint that announced “JESUS WILL PREVAIL” and “OBAMA IZ A MUSLIM!” On September 11 of the same year, certainly not an accidental choice, a small cube of granite was stolen from the upright stone bearing English and Russian. It was returned in 2013 and the man responsible for the theft caught. But the cube, along with an unofficial replacement made by another would-be vandal, remains safely locked away in Kubas’s office at the EGA, the organization deeded the stones and responsible for their conservation. More recent graffiti alluded to the ancient Egyptian goddess Isis, which drew the attention of federal authorities who wanted to ensure that the reference wasn’t to the other, terrorist group ISIS.

After circumambulating the monument in the persistent drizzle again, I retreated to the dry refuge of my car to sip gas station coffee from a Styrofoam cup, my many offenses to nature suddenly glaring in the shadow of the Guidestones. Before I left, a few other visitors arrived in pick-up trucks and sedans, taking quick pictures from underneath umbrellas and rain jackets.

I drove away, thinking of the Guidestones as roadside attraction and postmodern pastiche more than mystical site. Arguably, we exist in a Trump-era dystopia, but the Guidestones offered me no substantive wisdom on how to negotiate its particulars. But maybe I was missing the point. My fellow tourists and I were not the intended audience.

The Guidestones were designed for an even more distant future inspired, I imagine, by science fiction and Cold War anxieties: the post-apocalyptic subjugation of humans envisioned in Franklin James Schaffner’s The Planet of Apes (1968) or the tortured sufferers in the more nightmarish sequences of Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams (1990). And much like the ruined Statue of Liberty that Charlton Heston, playing a time-travelling astronaut, so famously stumbled upon in the former, I suspect the wonder the Guidestones will inspire may be different than what the makers intended—awe of the waning hubris of the late 20th century that they now ironically commemorate.

Finally, the Guidestones, led me to the Elberton Granite Museum and Exhibit. Following the instructions on the ground marker, I went there in search of more information. There wasn’t much more on the Guidestones, but I encountered a strange, fragmented statue as steeped in irony and failed pretensions as Schaffner’s sci-fi Lady Liberty: Dutchy, an exhumed Confederate monument. He is, I think, a contender for one of the Guidestones’ tag lines: “Elberton’s Most Unusual Monument.”

Click here to read about Rebecca’s encounter with Dutchy.